Asia

Will China’s $1.2 Trillion Trade Surplus Overwhelm Global Trade?

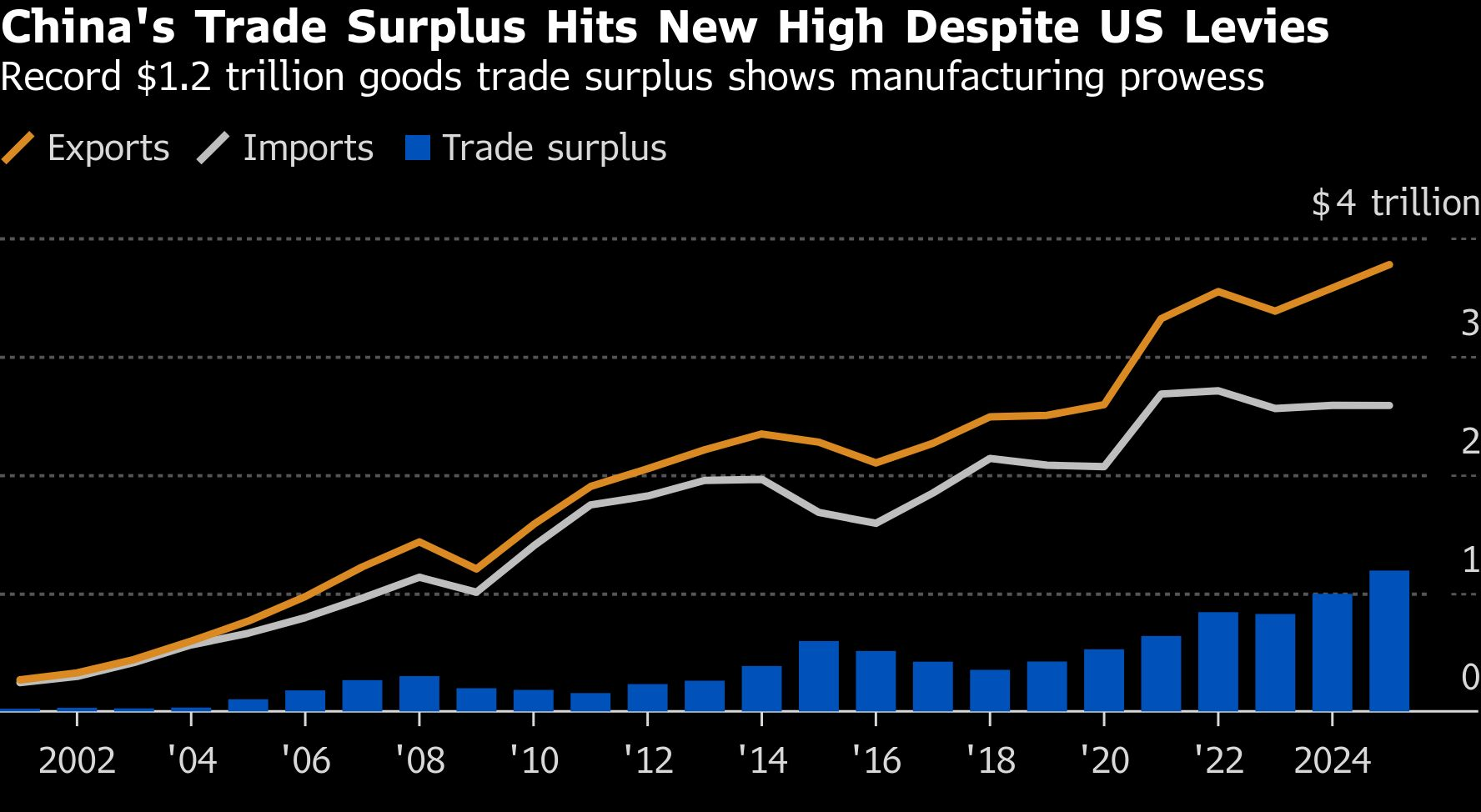

Just weeks into 2026, China’s economic data release has sent shockwaves through global financial markets and policy circles. Despite an escalating tariff war and predictions of export decline, China’s 2025 trade surplus reached an astonishing $1.2 trillion—the largest in modern economic history. This wasn’t supposed to happen. As Washington imposed punitive tariffs and Brussels contemplated countermeasures, conventional wisdom held that China’s export machine would finally slow. Instead, it accelerated, raising profound questions about the future architecture of global commerce and whether the international trading system can absorb such concentrated imbalances without fracturing.

The numbers reveal more than an economic anomaly. They expose a fundamental recalibration of global trade flows, the resilience of China’s manufacturing ecosystem, and the limitations of tariff-based trade policy. For policymakers in Washington, Brussels, and emerging economies alike, China’s record trade surplus represents both a challenge and a mirror—reflecting deeper questions about industrial competitiveness, currency dynamics, and the sustainability of growth models built on either consumption or production extremes.

The Record-Breaking Numbers: What the Data Really Shows

According to official data released by China’s customs authority in mid-January, China’s 2025 trade surplus reached approximately $1.189 trillion, with exports growing 5.9% year-on-year to $3.58 trillion while imports barely budged at $2.39 trillion. The magnitude staggers: this surplus exceeds the entire GDP of most nations and dwarfs previous records, including China’s own pre-pandemic peaks.

Breaking down the numbers reveals the mechanics of this surge. Exports to the United States—the focal point of trade tensions—actually declined sharply by double digits in the final months of 2025, precisely as anticipated. Yet this contraction was more than offset by explosive growth elsewhere. Chinese exports to ASEAN nations surged approximately 15%, to the European Union by 8-10%, and to Latin America and Africa by double-digit percentages, as Bloomberg’s analysis documented. China’s export base, it turns out, had quietly diversified far more effectively than Western analysts appreciated.

The import side tells an equally important story. While export values climbed, import growth flatlined at roughly 1%, reflecting tepid domestic demand and China’s increasing self-sufficiency in key inputs. This asymmetry—surging exports coupled with stagnant imports—transformed what might have been a respectable trade performance into a historic imbalance. China now accounts for approximately 14% of global goods exports but only 11% of imports, creating a structural gap that redistributes demand away from trading partners.

Drivers of the Surge: Deflation, Currency, and Diversification

Three interconnected forces propelled China’s trade performance to record heights, each reinforcing the others in ways that confounded trade policy aimed at a single pressure point.

Production-side deflation emerged as the unexpected catalyst. China’s producer price index remained negative or near-zero throughout 2025, meaning factory-gate prices actually fell even as global inflation persisted elsewhere. This deflationary environment—driven by overcapacity in manufacturing sectors from steel to electric vehicles—made Chinese goods increasingly price-competitive globally. A solar panel, EV battery, or textile manufactured in China cost 10-20% less than a year prior, while competitors in Vietnam, Mexico, or Eastern Europe struggled with rising input costs. For importers worldwide facing inflation-squeezed consumers, Chinese products became irresistible.

The renminbi’s carefully managed depreciation amplified this price advantage. The currency weakened approximately 5% against the dollar in 2025, making exports cheaper in foreign currency terms while raising the cost of imports. Whether this reflected deliberate policy or market forces remains debated, but the effect was unambiguous: Chinese exporters gained a compounding advantage. The Financial Times noted that Beijing walked a tightrope, allowing enough depreciation to support exports without triggering capital flight or Western accusations of currency manipulation.

Perhaps most significantly, China’s geographic diversification strategy matured. The Belt and Road Initiative, RCEP trade agreements, and targeted investment in emerging markets created alternative export corridors precisely when needed. When U.S. tariffs threatened 40% of potential exports, Chinese manufacturers had already cultivated relationships in Jakarta, Lagos, Mexico City, and Warsaw. These weren’t merely replacement markets but growing economies hungry for affordable industrial goods, consumer electronics, and infrastructure inputs that China produces at scale.

This diversification operated at multiple levels. Chinese firms established assembly operations in Vietnam and Mexico to circumvent tariffs—a practice trade officials call “transshipment” but which represents rational supply chain optimization. Meanwhile, exports of intermediate goods to these countries surged, meaning final products bore “Made in Vietnam” labels while value-added remained substantially Chinese. The New York Times analysis highlighted how this “tariff arbitrage” effectively neutralized much of Washington’s trade offensive.

Winners and Losers: Sectoral and Regional Impacts

The record surplus wasn’t evenly distributed across China’s economy. Electric vehicles, batteries, and solar panels emerged as star performers, with exports in these “new three” categories surging by 30-60% to global markets eager for energy transition technologies. Europe’s green transition targets and emerging market electrification created insatiable demand that only China’s manufacturing scale could meet. A European buyer could choose between a €35,000 Chinese EV or a €50,000 European alternative—and increasingly chose the former.

Traditional manufacturing sectors told different stories. Electronics and machinery maintained steady growth of 5-8%, benefiting from global digitalization trends and China’s dominance in semiconductor assembly and consumer electronics. However, textiles and apparel faced headwinds as production continued shifting to Bangladesh, Vietnam, and India, where labor costs remained lower. The surplus in these legacy sectors shrank, even as higher-value manufactured goods compensated.

Regionally, coastal manufacturing hubs in Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang captured the lion’s share of export growth, while interior provinces lagged. This geographic concentration reinforced China’s internal economic imbalances—precisely the problem Beijing’s “dual circulation” policy aimed to address. The export surge, paradoxically, may have delayed necessary rebalancing toward domestic consumption.

For China’s trading partners, the impacts varied dramatically. ASEAN nations benefited as both alternative markets and manufacturing partners, seeing Chinese investment and supply chain integration accelerate. European importers gained access to affordable goods that helped contain inflation, though manufacturers voiced growing concerns about unfair competition from subsidized Chinese rivals. The United States experienced the predicted surge in non-Chinese imports that were frequently Chinese in origin—the trade deficit persisted even as bilateral flows declined.

Emerging economies faced a more complex calculus. Affordable Chinese machinery, vehicles, and industrial inputs supported development and infrastructure projects. Yet domestic manufacturers in countries like India, Brazil, and South Africa struggled against Chinese competition, prompting protectionist responses. As one trade economist observed, China’s surplus represented simultaneous opportunity and threat—infrastructure enabler and industrial destroyer.

Geopolitical Ripple Effects: Tariffs, Protectionism, and Retaliation Risks

The record surplus arrives at a geopolitically fraught moment, potentially catalyzing a new wave of protectionist measures that could fragment global trade more decisively than anything witnessed since the 1930s.

Washington’s reaction has been predictably sharp. With the 2025 data confirming that tariffs failed to reduce the bilateral deficit meaningfully, voices across the political spectrum are demanding more aggressive measures. Proposals under discussion include universal tariffs on all Chinese imports, secondary sanctions on countries facilitating transshipment, and restrictions on Chinese investment in strategic sectors. The Wall Street Journal reported that bipartisan congressional coalitions view the surplus as vindication of hawkish trade policy, not evidence of its failure.

The European Union confronts its own dilemma. European consumers benefit from affordable Chinese goods that suppress inflation, yet manufacturers face existential threats from subsidized Chinese EVs and industrial products. Brussels has initiated anti-subsidy investigations and considered carbon border adjustment mechanisms, but internal divisions between manufacturing-heavy Germany and consumption-oriented economies complicate unified action. The surplus forces Europe to choose between consumer welfare and industrial policy—a choice it’s reluctant to make.

For emerging economies, China’s surplus creates a prisoner’s dilemma. Individual countries benefit from Chinese investment and affordable imports, yet collectively they risk long-term deindustrialization. India has imposed targeted tariffs and investment restrictions, while Brazil and South Africa debate similar measures. Yet aggressive countermeasures risk alienating a crucial trading partner and infrastructure financier. The result is a patchwork of inconsistent responses that leaves global trade governance weakened.

The currency dimension adds another layer of complexity. A $1.2 trillion surplus represents enormous downward pressure on the renminbi, which China’s central bank must counteract through intervention or capital controls. This accumulation of foreign exchange reserves—already the world’s largest—raises questions about currency manipulation that could trigger coordinated Western responses. Yet allowing the renminbi to appreciate would devastate export competitiveness, creating a policy trap Beijing may struggle to escape.

Perhaps most concerning is the erosion of multilateral trade governance. The WTO, already weakened, offers no clear mechanism to address such concentrated imbalances. Bilateral negotiations have proven ineffective. The risk is that countries increasingly resort to unilateral measures—tariffs, quotas, subsidies, and sanctions—that fragment global commerce into competing blocs. The record surplus, in this view, isn’t merely an economic statistic but a catalyst for systemic breakdown.

Can This Continue? 2026 Outlook and Policy Dilemmas

Projecting whether China can sustain or expand its record surplus involves weighing contradictory forces, each powerful enough to reshape trade flows dramatically.

Headwinds appear formidable. Global demand growth is slowing as major economies navigate post-pandemic adjustments and elevated interest rates. The tariff offensive will intensify—both from the U.S. and increasingly from Europe and emerging economies concerned about Chinese overcapacity. China’s demographic decline and rising labor costs erode competitiveness in labor-intensive sectors. Most significantly, the political tolerance for such concentrated imbalances is exhausted. Further surplus expansion risks triggering coordinated protectionist responses that could overwhelm even China’s diversification efforts.

Yet countervailing forces remain strong. China’s manufacturing ecosystem offers scale, speed, and cost advantages competitors struggle to match. The energy transition creates massive demand for Chinese-dominated technologies—EVs, batteries, solar panels—where alternatives remain years behind in cost and capacity. Belt and Road and RCEP integration continues deepening, creating trade corridors partially insulated from Western pressure. China’s ability to manage currency and deploy industrial subsidies gives it policy tools competitors lack.

The likely scenario isn’t simple continuation but rather volatility around a persistently high plateau. The surplus may moderate from $1.2 trillion but remain historically elevated—perhaps $800 billion to $1 trillion annually. Geographic composition will shift as some markets impose barriers while others open. Sectoral mix will evolve toward higher-value goods as low-end manufacturing continues migrating elsewhere.

Beijing faces its own policy dilemmas. The export surge masked deeper problems: weak domestic demand, deflation, property sector distress, and mounting local government debt. The record surplus reflects not just export strength but consumption weakness—Chinese households saving rather than spending. Rebalancing toward domestic consumption would reduce the surplus but requires politically difficult reforms: stronger social safety nets, reduced savings incentives, and allowing wages to rise faster than productivity.

There’s also a temporal dimension. China’s surplus may represent a last hurrah before demographic decline, rising costs, and supply chain diversification take their toll. Countries and firms are actively reducing China dependency—”de-risking” in diplomatic parlance. Vietnam, India, Mexico, and others are attracting investment that might have gone to China a decade ago. These shifts take years to materialize, meaning China’s export dominance may persist medium-term before eroding long-term.

Conclusion: A Turning Point for Global Trade?

China’s $1.2 trillion trade surplus represents more than an impressive economic statistic—it’s a stress test of global trade architecture, revealing fractures that may prove irreparable under current frameworks.

The surplus demonstrates that tariffs alone cannot rebalance trade relationships when cost advantages, manufacturing ecosystems, and alternative markets exist. It shows that global value chains have grown complex enough to route around bilateral restrictions. It confirms that concentrated economic power—whether American financial dominance or Chinese manufacturing supremacy—creates systemic risks that multilateral institutions can no longer manage.

Yet it also reveals vulnerabilities. China’s economy remains dangerously dependent on external demand even as trading partners grow hostile. The surplus itself evidence of imbalanced growth—too much production, too little consumption—that stores up future risks. Global tolerance for such concentration has limits, and those limits may be approaching.

The coming years will likely witness competing forces: China’s formidable manufacturing advantages against rising protectionism; globalization’s efficiency gains against geopolitical fragmentation; multilateral governance against unilateral power. Which force prevails will shape not just trade flows but the global economic order itself.

For investors, policymakers, and business leaders, several questions demand attention: Can Western economies rebuild manufacturing competitiveness without prohibitive costs? Will emerging markets become genuine alternatives to China or remain dependent suppliers? Can global trade governance adapt to concentrated power, or will it fracture into competing blocs? And perhaps most fundamentally: Is a $1.2 trillion surplus sustainable economically, or merely sustainable politically until it suddenly isn’t?

The answers will determine whether 2025’s record marks a peak or a plateau—and whether global trade can accommodate such imbalances or will be overwhelmed by them.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

UAE Stocks Fall as Fears of Prolonged Middle East Conflict Grip Investors — DFM, ADX Under Siege

The smoke was still rising over the Gulf when the trading screens flickered back to life.

After two unprecedented days of enforced silence — the UAE equity markets shuttered by regulatory decree as Iranian missiles rained down on Abu Dhabi and Dubai — UAE stocks fell sharply on March 4, delivering the kind of gut-punch to investor confidence that takes months, sometimes years, to fully repair. As the war in the Middle East now approaches its two-week mark — with drone and missile exchanges intensifying rather than abating — the question confronting every portfolio manager from London to Singapore is no longer whether the UAE’s markets will recover, but how long they can sustain the pressure of being caught in the crosshairs of the region’s most dangerous confrontation in a generation.

Investor caution has intensified as the war in the Middle East approaches the two-week mark, with heavy exchanges of drone and missile strikes across the region, unsettling markets that had spent the better part of the decade repositioning the UAE as a geopolitically neutral financial sanctuary. ZAWYA

The Market Numbers: A Reckoning in Red

The data tells a stark story. The DFM General Index, the main equities gauge of the Dubai Financial Market, closed the first post-closure session 4.71 per cent lower — its steepest single-day drop since mid-2022 — while the benchmark gauge of the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange ended the day 1.9 per cent lower, after falling more than 3 per cent at intraday lows. The National

The declines were across the board, with both the Dubai Financial Market and the Abu Dhabi Securities Exchange applying a temporary -5% lower price limit on securities to protect investors from extreme volatility. Aldar Properties, First Abu Dhabi Bank, Abu Dhabi Aviation, and Abu Dhabi National Hotels were among the stocks that hit the -5% limit. Dubai’s banking and airline stocks led the declines — Emirates NBD Bank and Mashreq closed 5% lower, while Air Arabia, the market’s sole airline stock, also declined nearly 5% to AED 5.14. TradingView

Major names such as Emaar Properties, Emaar Development, Deyaar Development, and Emirates NBD came under pressure, alongside logistics firm Aramex and infrastructure-related companies including DEWA, Salik, and Parkin. Gulf News

Key Market Performance Snapshot (March 4–14, 2026)

| Asset / Index | Move (Reopening Day) | Notable Detail |

|---|---|---|

| DFM General Index (DFMGI) | −4.71% | Steepest drop since May 2022 |

| ADX FTFADGI | −1.93% (−3.6% intraday) | Held above 200-day EMA |

| Emirates NBD | −5.0% (hit circuit) | Banking sector leader |

| Mashreq Bank | −5.0% (hit circuit) | Hit lower price limit |

| Emaar Properties | −4.93% | UAE’s flagship real estate stock |

| Air Arabia | ~−5.0% to AED 5.14 | Sole airline on DFM |

| DEWA / Salik | −5.0% (hit circuit) | Mobility/infrastructure linked |

| Aldar Properties (ADX) | −5.0% (hit circuit) | Abu Dhabi real estate bellwether |

| First Abu Dhabi Bank (FAB) | −5.0% (hit circuit) | UAE’s largest bank by assets |

| Gold (safe-haven) | +13% over six weeks | Inverse flight to safety |

| Crude oil | +~20% over six weeks | Hormuz disruption premium |

How We Got Here: The Arc of an Unprecedented Crisis

The conflict that is now reshaping Gulf financial markets began on Saturday, March 1, 2026, when coordinated US-Israeli military operations against Iran produced consequences that would reverberate far beyond the battlefield. The UAE’s financial regulator announced that its key exchanges in Dubai and Abu Dhabi would not immediately reopen after the weekend break amid the fallout of the US-Israeli attacks. The announcement came after the UAE was hit with hundreds of Iranian missile and drone attacks, including a strike on Abu Dhabi’s main airport that killed one person and wounded seven others. Al Jazeera

The UAE Capital Markets Authority announced that the ADX and DFM would be closed on Monday, March 2 and Tuesday, March 3, 2026, with the regulator continuing to “monitor developments in the region and assess the situation on an ongoing basis, taking any further measures as necessary.” The National

The two-day closure was, to put it plainly, historically extraordinary. Historically, no Middle Eastern state — including Israel during prior conflicts — had ever fully closed its stock exchange during a time of regional conflict. In prior exchanges, Israel modified trading hours, not days. The only modern analogues are Russia’s month-long freeze of the Moscow Exchange following its 2022 Ukraine invasion, and Egypt’s nearly two-month suspension during the Arab Spring upheaval of 2011. Al Jazeera

The symbolism of that comparison should not be lost on investors. In both precedents, the market closures preceded years of structural realignment.

The Strait of Hormuz: The World’s Most Expensive Chokepoint

No geopolitical variable concentrates the mind of global energy markets more immediately than the Strait of Hormuz — the 21-mile-wide channel through which the arteries of global commerce pulse. Iran’s strikes effectively blocked the Strait of Hormuz, the chokepoint through which roughly 20 million barrels of oil per day and nearly 20% of global LNG exports transit. A sustained Hormuz closure could push oil above $100 per barrel, spiking US CPI inflation toward 5%. War-risk insurance costs have reportedly jumped approximately 50%, adding hundreds of thousands of dollars per voyage and reducing global trade flow. Shipping reroutes around Africa add 10–14 extra days to deliveries, slowing just-in-time manufacturing supply chains. BeInCrypto

Iran’s new Supreme Leader Mojtaba Khamenei, in his first public comments following his predecessor’s death, said on Thursday that Tehran would keep the Strait of Hormuz closed and urged neighbouring countries to shut US bases on their territory or risk being targeted. ZAWYA That statement — part geopolitical ultimatum, part market-moving declaration — landed like a depth charge in energy trading rooms worldwide.

For the UAE, an economy whose extraordinary prosperity has been constructed on the premise of being both an oil-revenue beneficiary and a trade-neutral corridor, the irony is acute: the very geography that makes it valuable also makes it vulnerable.

Dubai’s Safe-Haven Brand: Tested, Not Broken — Yet

For two decades, Dubai’s value proposition to the world’s mobile capital was elegantly simple: maximum connectivity, minimum geopolitical friction. That narrative took its most serious blow yet on March 13, 2026. When debris from a successfully intercepted aerial threat, widely attributed to Iran by UAE air defence sources, struck the facade of a building in central Dubai near the DIFC Innovation Hub, it did far more damage than the structure itself. Investors and market watchers around the world saw cracks in the image that Dubai had spent two decades carefully polishing — an image of an unbreachable, neutral financial sanctuary in a turbulent neighbourhood. The Week

The UAE attracted $33.2 billion in FDI in 2025 and welcomed approximately 9,800 new millionaires in the same year. That extraordinary momentum is now facing its stiffest geopolitical test, and the world is watching whether the safe haven holds, or whether the smoke over the skyline marks a permanent shift in where global capital chooses to call home. The Week

The combined market capitalisation of the UAE exchanges stands at $1.1 trillion, the 19th highest in the world, carrying a 1.4 per cent weight on MSCI’s emerging markets benchmark, according to Bloomberg data. The National Capital at that scale does not flee quietly. It reprices, reroutes, and — in the worst case — relocates permanently.

Sector-by-Sector: Who Bears the Heaviest Burden?

Banking & Financial Services

The UAE’s banks entered this crisis from a position of structural strength. GCC banking systems carry robust capital buffers and have demonstrated through multiple prior stress periods — the 2020 pandemic, the 2015–16 oil correction — a capacity to maintain liquidity. Yet the market is pricing in something more insidious than near-term credit losses: a potential erosion of the correspondent-banking relationships and cross-border capital flows that underpin Dubai’s status as the Middle East’s financial clearing house. The flight of First Abu Dhabi Bank and Emirates NBD to their -5% circuit breakers on reopening day signals that institutional investors are not waiting to find out.

Real Estate

For UAE real estate stocks in the context of the Iran war, the dynamics are particularly complex. Indian buyers reportedly account for 20–30 per cent of prime Dubai residential property purchases, and high-net-worth individuals, family offices, and startup founders have parked billions in Dubai real estate and financial instruments. Disruption to DIFC’s operational ecosystem risks triggering capital reassessment, property transaction freezes, and turbulence in the remittance flows that many Indian families depend on. The Week Emaar Properties and Aldar’s near-5% drops are not merely equity corrections; they are referendum votes on the durability of Dubai’s real-estate premium.

Aviation & Tourism

Air Arabia’s near-5% decline reflects the raw arithmetic of a sector that cannot function when airspace is contested. Emirates confirmed that more than 100 flights would operate as UAE airspace partially reopened The National — a measure of normalisation that nonetheless underscores how profoundly abnormal conditions had become. Tourism, the sector Abu Dhabi and Dubai have invested billions to diversify into, faces a demand shock that will not be captured fully in equity prices until hotel occupancy and forward bookings data emerges in the coming weeks.

Energy Adjacents: The Counterintuitive Tailwind

Here lies the one sector where the conflict’s arithmetic inverts. Energy companies could receive support from rising oil prices, which have surged amid fears of supply disruptions linked to tensions around the Strait of Hormuz. As Saudi Arabia’s Aramco demonstrated during the UAE market closure by surging despite regional chaos, ADNOC and TAQA may see similar investor support Gulf News — a rerating driven not by fundamentals but by the premium embedded in every barrel of crude while Hormuz remains contested.

Investor Psychology: Between Panic and Price Discovery

The regulatory decision to apply -5% circuit breakers was a piece of sophisticated market engineering. The 5% cap offered some breathing space and partially curbed the initial panic among investors TradingView — preventing the kind of cascade selling that transforms a geopolitical repricing into a structural liquidity crisis. Market participants spent two days assessing regional developments while watching global markets and energy prices react to the escalating conflict. The initial session reflected rapid adjustment rather than panic selling — trading was dominated by price discovery as investors absorbed accumulated global and regional developments. Gulf News

Technically, both indices held above their 200-day EMA levels — DFMGI at Dh6,010 and FTSE ADX General Index at Dh10,060 — with the ADX closing above its 100-day EMA at Dh10,220. Gulf News Those technical floors matter enormously to algorithmic and institutional traders. Their preservation signals that this remains, for now, a fear-driven correction rather than a conviction-driven bear market.

“Equities in the United Arab Emirates are trading slightly lower, following a two-day closure aimed at protecting the Gulf state’s key markets amid the regional geopolitical developments. This temporary dip is likely to open up some interesting opportunities in the UAE’s accelerating long-term equity story,” Economy Middle East said Vijay Valecha, Chief Investment Officer at Century Financial — a view that encapsulates the tension every long-term investor now faces: the difference between a buying opportunity and a structural inflection point can only be assessed in hindsight.

Forward Scenarios: Three Paths Through the Fog

Scenario One — Rapid De-escalation (Low Probability, Near-Term): A ceasefire brokered through Qatari or Omani intermediaries within the next fortnight would trigger a sharp recovery rally. Historical precedent — the 2019 Abqaiq strikes in Saudi Arabia, the 2020 Soleimani assassination — suggests Gulf markets rebound powerfully once clarity returns. The UAE’s structural story (FDI pipeline, expo legacy infrastructure, diversification momentum) remains intact.

Scenario Two — Prolonged Stalemate (Most Probable): Trump’s stated policy goals — low inflation and $2 gas — conflict directly with a prolonged Iran conflict, which analysts say creates political pressure for a swift resolution. BeInCrypto A managed standoff, with Hormuz partially operational and oil stabilising between $90–$110, would produce a range-bound market: energy-related stocks supported, consumer and tourism stocks under pressure, and institutional foreign capital adopting a cautious “wait and observe” posture.

Scenario Three — Escalation to Regional War (Tail Risk, Severe Impact): Full Hormuz closure, sustained strikes on UAE infrastructure, and the paralysis of Dubai International Airport as a global aviation hub would constitute a genuine crisis for UAE equity markets. Dubai’s government has maintained a firm “business as usual” posture, with DIFC confirming full operational availability. The Week But if that posture cracks — if the messaging diverges from operational reality — the repricing would be severe.

The Longer View: Precedent, Resilience, and What Dubai Has Always Sold

History is instructive, if not entirely reassuring. The Gulf has endured the Iran-Iraq War, the first and second Gulf Wars, the 2006 Lebanon conflict, and the post-Arab Spring regional convulsions — and in each case, Dubai and Abu Dhabi emerged not merely intact but stronger, having absorbed displaced capital from less stable neighbours. The UAE’s model — benign authoritarianism married to cosmopolitan commerce — has consistently converted regional instability into competitive advantage.

But this moment is different in one critical respect: for the first time, the UAE itself is the theatre, not merely the sanctuary adjacent to one. The debris on a DIFC facade is not a metaphor; it is a datapoint that every institutional risk committee in New York, London, and Tokyo will process in the coming weeks.

By looking at the Saudi roadmap — which showed that the initial selling was short-lived and replaced by a focus on oil-price-driven gains — investors can approach the DFM and ADX with a balanced perspective. Gulf News That parallel is encouraging. Whether it holds depends entirely on decisions being made not in trading rooms, but in military command centres across the region.

Frequently Asked Questions: UAE Stocks and the Middle East Conflict

Why did UAE stocks fall so sharply when markets reopened? Markets were closed for two days while geopolitical events unfolded globally. The reopening session was a compressed price-discovery process — two days of global news, energy repricing, and risk-off sentiment priced in simultaneously.

What impact do Iran missile strikes have on UAE stocks? Direct strikes on UAE infrastructure — including Abu Dhabi airport — raise risk premiums across all asset classes, while signalling that the UAE’s traditional neutrality has been compromised. Banking and real estate stocks, as core pillars of UAE equity indices, bear the heaviest burden.

Is UAE real estate safe during the Iran war? Prime Dubai property continues to transact, and the government has maintained operational normalcy. However, forward bookings, luxury tourism, and foreign-buyer demand are under pressure — particularly from Indian and European HNI segments most sensitive to security perceptions.

What sectors could outperform in a prolonged Middle East conflict scenario? Energy producers (ADNOC, TAQA), defence-adjacent infrastructure, and gold-linked assets tend to outperform in sustained conflict environments. Banks with strong domestic deposit bases and minimal regional exposure may also prove relatively resilient.

Conclusion: The Price of Location

There has always been a geopolitical premium embedded in Gulf equity valuations — a discount applied to reflect the neighbourhood’s volatility. For years, the UAE’s extraordinary governance, economic diversification, and logistical prowess compressed that discount to near-zero. The events of the past two weeks have re-expanded it.

The fundamental UAE story — 9 million-strong consumer economy, $33 billion annual FDI, world-class infrastructure, and a regulatory environment that courts global capital with genuine sophistication — has not changed. But the backdrop against which that story is told has. There might be a way to be resilient, but there is no going back. The Week

For investors, the question is not whether to believe in the UAE’s long-term trajectory. That case remains compelling. The question is at what price, and with what geopolitical assumptions, that belief is worth making now.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

Pakistan SOE Salary Cuts of Up to 30%: Austerity, Oil Shock, and the IMF Tightrope

When a geopolitical earthquake in the Gulf meets a fragile emerging-market economy, the tremors travel fast — and reach deep into the pay packets of millions of public workers.

The Man at the Pump — and the Policy Behind It

Sohail Ahmed, a 27-year-old delivery rider in Karachi supporting a family of seven, is blunt about the government’s emergency measures. “There is no benefit to me if they work three days or five days a week,” he told Al Jazeera. “For me, the main concern is the fuel price because that increases the cost of every little thing.” Al Jazeera

Ahmed’s frustration is both viscerally human and economically precise. On the morning of Saturday, March 14, 2026, Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif chaired a high-level review meeting in Islamabad. The outcome was stark: salary deductions of between 5% and 30% approved for employees of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and autonomous institutions — extending austerity cuts already applied to the civil service — as part of a drive to mitigate the fallout from the ongoing Middle East war. Geo News

The announcement formalised a fiscal posture that has been hardening for a fortnight. It also sent an unmistakable signal to Islamabad’s most important creditor: the International Monetary Fund.

What SOEs Are — and Why They Matter So Much

To understand what is at stake, it helps to understand what state-owned enterprises actually are. In Pakistan, SOEs are government-owned or government-controlled companies spanning power generation, aviation, railways, ports, petrochemicals, steel, and telecommunications. They are simultaneously the backbone of essential services and, for decades, the most persistent drain on public finances. Unlike a civil servant whose salary comes from tax revenues, SOE workers are technically employed by commercial entities — many of which run structural losses that are ultimately underwritten by the exchequer.

Pakistan’s SOEs bled the exchequer over Rs 600 billion in just six months of FY2025 alone. Todaystance The IMF has made SOE governance reform a pillar of every engagement with Pakistan for years, and the current $7 billion Extended Fund Facility (EFF), approved in September 2024, is no exception. The 37-month programme explicitly requires the authorities to improve SOE operations and management as well as privatisation, and strengthen transparency and governance. International Monetary Fund

When a government imposes salary discipline on those same entities during a crisis, it is doing two things at once: cutting costs in the present, and — at least symbolically — demonstrating to Washington and Washington-adjacent institutions that reform intent is real.

The Scale and Mechanics of the Cuts

At a Glance — Pakistan’s March 2026 Austerity Package

- SOE/autonomous institution employees: 5%–30% salary reduction (tiered, based on pay grade)

- Federal cabinet ministers and advisers: full salaries foregone for two months

- Members of Parliament: 25% salary cut for two months

- Grade-20+ civil servants earning over Rs 300,000/month: two days’ salary redirected to public relief

- Government vehicle fleet: 60% grounded; fuel allocations cut by 50%

- Foreign visits by officials: banned (economy class only for obligatory trips)

- Board meeting fees for government-board representatives: eliminated

- March 23 Pakistan Day embassy celebrations: directed to be observed with utmost simplicity

- All savings: ring-fenced exclusively for public relief

The meeting also decided that government representatives serving on the boards of corporations and other institutions would not receive board meeting fees, which will instead be added to the savings pool. The Express Tribune The prime minister directed concerned secretaries to implement and monitor all austerity measures, submitting daily reports to a review committee. Geo News

The tiered structure — 5% at the lower end, 30% at the top — reflects a political calculation as much as a fiscal one. Flat cuts hit low-income workers hardest and generate the most social friction. A progressive scale preserves a veneer of equity. Whether that veneer survives contact with household budgets in the coming weeks remains to be seen.

Why Now? The Strait of Hormuz and Pakistan’s Achilles Heel

The proximate cause of Islamabad’s emergency posture is a crisis that began not in Pakistan but in the Persian Gulf. On February 28, 2026, the United States and Israel initiated coordinated airstrikes on Iran under Operation Epic Fury, targeting military facilities, nuclear sites, and leadership, resulting in the death of Supreme Leader Khamenei. Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps declared the Strait of Hormuz closed, and within days tanker traffic through the world’s most important oil chokepoint had ground to a near halt, with over 150 ships anchoring outside the strait. Wikipedia

The strait is a 21-mile-wide waterway separating Iran from Oman. In 2024, oil flow through the strait averaged 20 million barrels per day, the equivalent of about 20% of global petroleum liquids consumption. U.S. Energy Information Administration For Pakistan, the chokepoint is existential: the country relies on imports for more than 80% of its oil needs, and between July 2025 and February 2026, its oil imports totalled $10.71 billion. Al Jazeera

As of March 13, 2026, Brent crude has risen 13% since the war began, hitting $100 a barrel. If the situation does not move towards resolution, Brent could reach $120 a barrel in the coming weeks. IRU

The LNG exposure is equally severe. Qatar and the UAE account for 99% of Pakistan’s LNG imports. Seatrade Maritime LNG now provides nearly a quarter of Pakistan’s electricity supply. A Qatar production stoppage following Iranian drone strikes on Ras Laffan has thus hit Pakistan in the electricity sector and the fuel sector simultaneously — a dual shock for which the country has limited storage buffers and virtually no domestic alternative.

“Pakistan and Bangladesh have limited storage and procurement flexibility, meaning disruption would likely trigger fast power-sector demand destruction rather than aggressive spot bidding,” said Go Katayama, principal insight analyst at Kpler. CNBC

Pakistan has responded with speed if not sophistication. On March 4, Pakistan officially requested that Saudi Arabia reroute oil supplies through Yanbu’s Red Sea oil port, with Saudi Arabia providing assurances and arranging at least one crude shipment to bypass the closed strait. Wikipedia

The Embassy Directive: Austerity as Theatre and as Signal

Perhaps no single measure in the package better illustrates the dual logic of crisis governance than the instruction to Pakistani embassies worldwide. PM Shehbaz directed all Pakistani embassies worldwide to observe March 23 celebrations with utmost simplicity. Geo News

Pakistan Day — commemorating the 1940 Lahore Resolution that set the country on its path to independence — is typically marked by receptions at missions abroad that range from modest gatherings to elaborately catered affairs. This year, the message from Islamabad is: not now.

The directive is, on one level, symbolic. The savings generated by cutting embassy receptions are financially immaterial. But symbolism in fiscal signalling is rarely immaterial. Pakistan’s government is communicating — to citizens at home who are queueing at petrol stations and adjusting Eid budgets, and to investors and creditors watching from afar — that the state is willing to absorb visible sacrifice. The IMF counts perception as well as arithmetic.

Geopolitical Stress-Testing an Already Fragile Fiscal Framework

Pakistan’s public finances were already under acute pressure before the Hormuz crisis struck. Tax collection remained Rs 428 billion below the revised FBR target during the first eight months of the fiscal year, and the country may find it difficult to achieve its previously agreed tax-to-GDP ratio target of 11% for FY2025–26. Pakistan Observer

Against that backdrop, the IMF’s most recent reviews present a mixed picture. Pakistan achieved a primary surplus of 1.3% of GDP in FY25 in line with targets, gross reserves stood at $14.5 billion at end-FY25, and the country recorded its first current account surplus in 14 years. International Monetary Fund These are genuine achievements, hard-won through painful monetary tightening and a depreciation-induced adjustment.

But an oil shock of this magnitude — Brent crude rising from around $70 to over $110 per barrel within days of the conflict’s escalation, with analysts forecasting potential rises to $100 per barrel or higher if disruptions persisted Wikipedia — could erase months of fiscal progress in weeks. Every $10 per barrel rise in global crude prices adds roughly $1.5–2 billion to Pakistan’s annual import bill, according to analysts. A $40 spike, even partially absorbed, threatens the current account surplus, the reserve-rebuilding trajectory, and the primary surplus target in one stroke.

The government’s response — grounding vehicles, cutting salaries, banning foreign travel — is essentially a demand-side shock absorber. While some measures aim to show solidarity, their effectiveness on actual fuel demand remains in question, since the stopping of Cabinet members’ salaries and cuts to parliamentarians’ pay are essentially meant to demonstrate solidarity rather than conserve fuel in any meaningful way. Pakistan Today The analysis is correct. Energy analyst Amer Zafar Durrani, a former World Bank official, noted that roughly 80% of petroleum products are used in transport, meaning the country’s oil dependence is fundamentally a mobility problem Al Jazeera — one that no amount of reduced official-vehicle usage can meaningfully address.

Social Impact: Who Actually Bears the Cost

The SOE salary cuts will land on a workforce that is already under financial strain. Pakistan’s inflation, while having fallen dramatically from its 2023 peak of over 38%, is being pushed back up by the petrol price shock. The recent energy crisis triggered the largest fuel price increase in the country’s history, with petrol costing $1.15 a litre and diesel at $1.20 a litre — a 20% jump from the prior week. Al Jazeera

State-owned enterprises in Pakistan employ hundreds of thousands of workers, many in lower-middle-income brackets. A bus driver at Pakistan Railways, a junior technician at WAPDA (Water and Power Development Authority), or a clerk at the Steel Mills — all will see monthly take-home pay contract by between 5% and 30%, at precisely the moment transport costs and grocery bills are climbing. The government’s pledge that all savings will be ring-fenced for public relief offers some rhetorical comfort, but the mechanisms for distribution remain unspecified.

This asymmetry — pain certain for workers, relief uncertain for the poor — has been the structural weakness of every Pakistani austerity programme in living memory.

Historical Parallels and Reform Precedents

Pakistan has deployed austerity rhetoric many times before. It has also, many times before, proved unable to sustain it. The country has entered IMF programmes on 25 separate occasions since joining the Fund in 1950, often reversing structural reforms once the immediate crisis passed. The circular debt in Pakistan’s power sector has crossed Rs 4.9 trillion, largely due to inefficiencies, poor recovery ratios, and delays in tariff rationalisation. Meanwhile, SOEs continue to bleed financially, and on the political front, frequent changes in policy direction, weak enforcement of reforms, and resistance from vested interest groups pose major risks to continuity. Todaystance

The global parallel most instructive is not another emerging market crisis but rather a structural pattern: when oil shocks hit import-dependent countries with high SOE employment, the response typically oscillates between genuine reform opportunity and short-term retrenchment. Indonesia’s restructuring after the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis — which included painful but ultimately durable SOE privatisations — offers one model. Argentina’s repeated failure to hold fiscal consolidation gains through successive oil and commodity shocks offers the cautionary counterpoint.

Pakistan’s current challenge is to use this external shock as a reform accelerant rather than a mere political prop. The IMF’s third review under the current EFF, which will assess progress in the coming months, will determine whether the Fund sees these measures as sufficient structural movement or as cosmetic gestures.

What Comes Next: The IMF Review, Privatisation, and Credibility

According to the IMF, upcoming review discussions will assess Pakistan’s progress on agreed reform benchmarks and determine the next phase of loan disbursements. The implementation of the Governance and Corruption Diagnostic Report and the National Fiscal Pact will be central to the talks, particularly for the release of the next loan tranche. Energy Update

The current austerity measures, if implemented with the rigor of the daily reporting mechanism the prime minister has mandated, offer two potential gains. First, they provide a quantifiable demonstration of demand compression that the IMF values in its assessment of programme adherence. Second, extending salary discipline to SOEs — entities that operate in the nominally commercial rather than the governmental sphere — is a step, however modest, toward the SOE governance reforms that Washington has been pushing Islamabad to adopt since at least 2019.

The privatisation agenda is the harder test. The IMF has explicitly called for SOE governance reforms and privatisation, with the publication of a Governance and Corruption Diagnostic Report as a welcome step. International Monetary Fund Salary cuts keep workers in post and institutions intact; privatisation means structural change that generates permanent fiscal relief but also generates political resistance. The Pakistan Sovereign Wealth Fund, created to manage privatisation proceeds, remains operationally nascent.

A Measured Verdict

Pakistan’s March 2026 austerity package is simultaneously more than it appears and less than is needed.

It is more than it appears because the extension of salary cuts to SOEs — entities that have historically been treated as patronage preserves immune to market discipline — marks a genuinely wider perimeter for fiscal tightening than previous exercises. The daily reporting mandate, the board-fee elimination, the embassy directive: these collectively suggest a government that has at least understood the optics of credibility, if not yet fully operationalised its substance.

It is less than is needed because the structural drivers of Pakistan’s oil vulnerability — import dependence exceeding 80%, an LNG supply chain concentrated in a now-disrupted region, a transport sector consuming four-fifths of petroleum products — are entirely untouched by the package. Salary cuts and grounded ministerial vehicles are fiscal band-aids on an energy-architecture wound.

The coming weeks will clarify how durable the measures are and how seriously the IMF assesses them. A credible, sustained austerity programme — even one born of external shock rather than endogenous reform will — would improve Pakistan’s negotiating posture for the next tranche, steady foreign exchange reserves, and marginally restore the fiscal space that the oil shock is burning away.

Whether that translates into the deeper SOE privatisation and energy diversification that the country’s long-run fiscal sustainability actually demands is the question that March 23’s simplified embassy celebrations will not answer — but that every subsequent IMF review will insist on asking.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

IJM Board Rejects Sunway’s RM11bn Takeover as ‘Not Fair’ — 46% Discount Exposed

A unanimous board rejection, an independent valuation gap that beggars belief, and a political firestorm over Bumiputera rights. Malaysia’s biggest corporate drama of 2026 just reached its watershed moment.

Somewhere between the glass towers of Kuala Lumpur’s financial district and the legal filing rooms of Bursa Malaysia’s exchange, a RM11 billion gambit unravelled in slow motion on Friday. IJM Corporation Bhd’s board unanimously recommended that shareholders reject Sunway Bhd’s conditional voluntary takeover offer of RM3.15 per share, after appointed independent adviser M&A Securities declared the bid “not fair and not reasonable.” Free Malaysia Today The language was clinical. The implications were seismic.

M&A Securities found the offer price represents a discount of between RM2.69 and RM3.33 per share — roughly 46.1% to 51.4% below IJM’s estimated sum-of-parts value Scoop of between RM5.84 and RM6.48 per share. In plain English: Sunway’s opening bid, dressed up as a transformational merger, was asking IJM shareholders to surrender a blue-chip Malaysian conglomerate at roughly half its independently assessed worth. For a deal this size, that is not a negotiating discount. That is a devaluation.

The IJM Sunway takeover rejection now stands as one of the most decisive and well-reasoned rebuffs in Malaysian corporate history — a verdict that reverberates across ASEAN boardrooms, foreign investor portfolios, and the charged political terrain of Bumiputera economic policy.

How the RM11 Billion Bid Was Born — and Why It Was Always Controversial

The origins of this Malaysia construction takeover 2026 saga trace back to 12 January, when Sunway Bhd tabled a conditional voluntary offer to acquire all 3.51 billion outstanding shares in IJM Corp at RM3.15 per share — a total consideration of RM11.04 billion, structured as 10% cash (RM0.315 per share) and 90% via new Sunway shares valued at RM2.835 each, based on an issue price of RM5.65 per new Sunway share. BusinessToday

On paper, the rationale was compelling. A combined Sunway-IJM entity would create Malaysia’s largest integrated property-construction conglomerate, able to compete on a genuinely ASEAN scale at a moment when regional infrastructure spending is entering a multi-decade supercycle. Sunway’s founder and executive chairman, Tan Sri Jeffrey Cheah, framed the deal as a nation-building exercise — a champion ready to bid for mega-projects from Johor’s Forest City development to Indonesia’s new capital, Nusantara.

But the market read it differently. IJM’s shares tumbled as much as 16% on January 19, plunging to a three-month low of RM2.34, prompting Bursa Malaysia to suspend intra-day short-selling of the stock. Free Malaysia Today Investors were not celebrating a strategic premium. They were selling on the belief that the offer undervalued IJM and the political controversy surrounding the deal made its completion far from certain.

Within days, the controversy metastasised. UMNO Youth chief Datuk Dr Akmal Saleh publicly raised concerns that the takeover could dilute the equity interests of the Malaysian government and the rights of the country’s Bumiputera majority, while the Malay Businessmen and Industrialists Association also questioned the deal. Bloomberg For any corporate transaction in Malaysia, where affirmative-equity policies remain politically sensitive and government-linked investment companies (GLICs) serve as the pillars of the capital markets, this kind of political headwind is not incidental noise. It is structural resistance.

The 46–51% Discount: What ‘Not Fair and Not Reasonable’ Actually Means

The phrase “not fair and not reasonable” in Malaysian securities law has a precise, two-limbed meaning. An offer is not fair when the price does not reflect the target company’s intrinsic value; it is not reasonable when accepting shareholders would be worse off than simply remaining shareholders in the status quo. The Sunway RM11 billion IJM bid discount managed to fail both tests simultaneously — an analytical verdict rarely achieved at this magnitude of deal size.

M&A Securities’ circular filed with Bursa Malaysia found the RM3.15 per share offer represents a 46.1% discount to the estimated low value of IJM shares at RM5.84, and a 51.4% discount to the estimated high value of RM6.48. The Star The assessment uses a sum-of-parts valuation methodology — the standard approach for diversified conglomerates — which values each business division individually before aggregating. IJM’s sprawling portfolio spans toll roads, ports (including the strategic Kuantan Port), property development, construction, manufacturing, and plantation assets. Each line generates independently supportable cashflows. The IJM sum-of-parts valuation Sunway gap is not a rounding error. It is a canyon.

To contextualise just how extraordinary this discount is: comparable ASEAN construction and infrastructure mergers typically offer premiums of 15–30% to the pre-announcement share price, not discounts of nearly half. The implied value fell further to RM3.08 per share once Sunway’s two-sen interim dividend — announced on 25 February — was factored in, deepening the effective discount to 47.3% and 52.4% against the low and high valuation estimates respectively. The Star

Structurally, too, the deal’s composition amplified the unfairness argument. Nine-tenths of the consideration is paid not in cash but in newly issued Sunway shares — shares that M&A Securities assessed are already trading at premium multiples that embed substantial future growth expectations. Accepting those shares at that price, in exchange for IJM equity valued at a significant discount, is a double-compression trade that no disciplined institutional investor should accept without resistance.

What Minority Status in Sunway Would Really Cost IJM Shareholders

The control dimension of this story deserves sharper focus than it has received in the local financial press, and it is central to understanding why IJM shareholders should reject Sunway’s offer.

IJM shareholders who accept the offer would transition from being 100% equity holders in IJM — with full voting rights, direct asset exposure, and dividend control — to holding approximately a 20.6% minority stake in the combined Sunway entity. The Star That dilution is not merely numerical. It represents a qualitative transformation in shareholder rights.

As a minority stakeholder in Sunway, an IJM shareholder would have no meaningful ability to influence capital allocation, dividend policy, management decisions, or strategic direction. They would assume exposure to the integration risks of merging two large, culturally distinct conglomerates with different asset compositions. They would lose direct ownership of IJM’s strategic infrastructure — including four toll-road concessions and the Kuantan Port, which sits at the heart of Malaysia’s deepening trade relationship with China under the Belt and Road corridor.

M&A Securities made this point explicitly: as minority shareholders, accepting holders would assume significant integration, execution and transitional risks arising from the combination of two sizeable and diversified conglomerates with distinct operating models, asset compositions, and management cultures. The Star The advisory language, stripped of its legalese, is unambiguous: the deal trades known, direct ownership for uncertain, diluted exposure.

The Shadow Over the Deal: MACC, the UK Fraud Office, and Governance Questions

No analysis of the IJM board recommends reject Sunway takeover story is complete without confronting the extraordinary governance cloud that has hung over IJM throughout the bid process.

By March 4, Malaysia’s Anti-Corruption Commission had opened three separate investigation papers relating to IJM Corporation, including an inquiry into financial transactions and overseas investments worth approximately RM2.5 billion, a bribery case involving a project, and a probe into the Sunway share transaction itself. BERNAMA MACC chief commissioner Tan Sri Azam Baki confirmed active cooperation with the UK’s Serious Fraud Office in what he described as an ongoing, multi-jurisdictional investigation.

Critics including the Malay Chamber of Commerce warned that any takeover could undermine Bumiputera ownership in IJM, where government-linked investment companies currently control more than 50% of the shareholding. The Corporate Secret The Ministry of Finance subsequently confirmed that GLICs held a combined 45% equity interest in IJM as of 30 January 2026 — a figure that frames the deal not as a purely private-sector transaction but as a de facto restructuring of public savings.

For the foreign institutional investors who collectively form a significant slice of both companies’ free float, this combination of valuation uncertainty, regulatory investigation, and political sensitivity is precisely the kind of environment that prompts capital to step back and wait.

The Macro Lens: ASEAN Consolidation, Infrastructure Cycles, and Foreign Capital

The IJM-Sunway saga unfolds against a backdrop that gives it significance beyond two Malaysian companies. Southeast Asia is entering what the Asian Development Bank estimates will be a US$210 billion annual infrastructure investment cycle through the 2030s, driven by energy transition infrastructure, data centre buildouts, urbanisation, and post-pandemic industrial reshoring.

In this environment, the logic of creating regional construction champions has real merit. ASEAN property developers merger Malaysia dynamics are not illusory — consolidation that creates companies capable of competing for billion-dollar projects across Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Bangladesh is strategically sound. The question has always been price, governance, and process — not direction.

What the IJM Sunway impasse reveals, however, is that Malaysia’s capital markets are not yet willing to accept large-scale ASEAN consolidation at valuations that disadvantage existing shareholders. The independent adviser’s verdict, the board’s unanimous alignment, and the institutional shareholder base’s likely disposition all point toward a rejection outcome that will reverberate beyond Malaysia’s borders. Foreign fund managers watching from Singapore, Hong Kong, and London will note that Malaysia’s regulatory and advisory infrastructure functioned as designed — providing substantive, independent analysis rather than rubber-stamping a politically connected deal.

That is a positive signal for the long-term credibility of Bursa Malaysia as an investable market. The short-term message, however, is more complicated: Malaysia’s largest infrastructure assets remain fragmented, and the path toward sector champions capable of competing regionally just got harder.

Jeffrey Cheah’s Exit Clause — and What Happens Next

Sunway founder Jeffrey Cheah, speaking to reporters on Friday, confirmed the group is prepared to walk away if IJM shareholders do not accept the offer by the April 6 deadline. “There’s no compulsion for the shareholders to sell to us,” Cheah said, adding simply: “We walk away.” Bloomberg

That equanimity — whether genuine or tactical — suggests Sunway understands the arithmetic. With the IJM board unanimously opposed, independent advice formally on record, GLICs holding a controlling block likely to follow the board’s recommendation, and an active MACC investigation casting a shadow, the conditions for a successful takeover have effectively evaporated. Sunway’s own share price trajectory will now be closely watched: a failed large acquisition attempt can, paradoxically, unlock value for the acquirer by removing the dilution risk embedded in the share issuance component of the offer.

The offer window remains open until 5pm on April 6, 2026. An EGM on March 26 will give shareholders a formal platform to voice their position. But the trajectory is clear. Unless Sunway revises its offer materially — and there is no indication it will — this Malaysia construction takeover 2026 will end in failure, becoming a case study in valuation discipline, governance complexity, and the limits of strategic vision unmatched by fair commercial terms.

The Columnist’s Verdict: A Justified Rejection, and a Missed Opportunity

The IJM board and its independent adviser have done exactly what they should do. The Sunway IJM offer not fair finding is not an ideological verdict; it is a financial one. A 46–51% discount to independently computed sum-of-parts value is not a negotiating position — it is an insult to shareholders who have held IJM through multiple economic cycles, infrastructure downturns, and pandemic-era uncertainty. Institutional investors who hold IJM on behalf of Malaysian pensioners and ordinary savers cannot, in good conscience, accept that exchange.

What makes this story genuinely important, however, is what it leaves unresolved. Malaysia’s construction sector fragmentation is a real competitive disadvantage. The country’s infrastructure ambitions — high-speed rail, the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone, renewable energy buildout — require contractors of regional scale and financial depth. The failure of this particular deal does not make the case for consolidation disappear. It makes the need for a better-structured, more fairly priced next attempt more urgent.

Sunway, for its part, remains a formidable operator — financially disciplined, well-governed, and with the operational depth to absorb a large acquisition. Jeffrey Cheah built one of Asia’s most respected property-construction empires over four decades. The vision to create a regional champion is not the problem. The price was.

When the right deal — at the right price, with the right governance protections, free of regulatory clouds — is eventually presented, Malaysia’s capital markets will be watching. For now, the answer from IJM’s board, its independent adviser, and, in all probability, its shareholders is unambiguous: not at RM3.15.

The offer for IJM shares remains open for acceptance until 5pm on 6 April 2026.

Further Reading

- Bursa Malaysia — IJM Corporation Bhd Filings

- Bloomberg: Sunway Willing to Walk Away If IJM Bid Rejected

- Bloomberg: Sunway’s IJM Bid Questioned Over Bumiputera Rights

- Nikkei Asia: Malaysia’s IJM Urges Shareholders to Reject Sunway Takeover Bid

- Bernama: Three Investigation Papers Opened Against IJM Corporation

- The Edge Malaysia: Sunway’s Offer for IJM Not Fair, Not Reasonable

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

-

Markets & Finance2 months ago

Markets & Finance2 months agoTop 15 Stocks for Investment in 2026 in PSX: Your Complete Guide to Pakistan’s Best Investment Opportunities

-

Analysis1 month ago

Analysis1 month agoBrazil’s Rare Earth Race: US, EU, and China Compete for Critical Minerals as Tensions Rise

-

Banks2 months ago

Banks2 months agoBest Investments in Pakistan 2026: Top 10 Low-Price Shares and Long-Term Picks for the PSX

-

Investment2 months ago

Investment2 months agoTop 10 Mutual Fund Managers in Pakistan for Investment in 2026: A Comprehensive Guide for Optimal Returns

-

Asia2 months ago

Asia2 months agoChina’s 50% Domestic Equipment Rule: The Semiconductor Mandate Reshaping Global Tech

-

Global Economy3 months ago

Global Economy3 months agoPakistan’s Export Goldmine: 10 Game-Changing Markets Where Pakistani Businesses Are Winning Big in 2025

-

Analysis3 weeks ago

Analysis3 weeks agoTop 10 Stocks for Investment in PSX for Quick Returns in 2026

-

Global Economy3 months ago

Global Economy3 months ago15 Most Lucrative Sectors for Investment in Pakistan: A 2025 Data-Driven Analysis