Opinion

The West’s Last Chance: Building a New Global Order

The drone strikes came at dawn. On a January morning in 2026, another wave of Russian missiles arced across Ukrainian skies, while in Khartoum, the sound of artillery fire echoed through emptied streets as Sudan’s civil war ground into its third year. In Gaza, the fragile ceasefire negotiated months earlier showed fresh signs of strain. These aren’t disconnected tragedies flickering across our screens—they’re symptoms of a deeper rupture. The world has transformed more profoundly in the past four years than in the previous three decades, and the international order that once promised stability now resembles a house with crumbling foundations.

We are living through the death throes of the post-Cold War era. The optimism that followed 1989—when Francis Fukuyama proclaimed the “end of history” and democracy seemed destined to sweep the globe—now feels like ancient hubris. The very forces that were supposed to bind nations together—trade networks, energy interdependence, digital technology, and information flows—have become weapons in a new kind of global conflict. The liberal international order is fracturing, and the West faces a choice more consequential than any since the Marshall Plan: adapt to build a new global order that reflects today’s realities, or watch its influence dissolve into irrelevance.

The window for action is narrow. Between 2026 and 2030, decisions made in Washington, Brussels, and allied capitals will determine whether the twenty-first century belongs to multipolar chaos or to a reformed, resilient system of global governance. This is the West’s last chance—not to restore hegemony, but to help architect something more sustainable.

Why the Liberal International Order Is Crumbling

The post-1945 international order, refined after the Cold War, rested on three pillars: American military and economic dominance, a web of multilateral institutions from the UN to the WTO, and an assumption that globalization would inevitably spread liberal democracy and market capitalism. Each pillar is now compromised.

Start with the numbers. Global power is dispersing at unprecedented speed. China’s economy has grown from 4% of global GDP in 2000 to approximately 18% today, while the combined GDP of the G7 has shrunk from 65% to around 43% of world output. India is projected to become the world’s third-largest economy by 2027. The “rise of the rest” isn’t a future scenario—it’s present reality.

But economic redistribution alone doesn’t explain the order’s collapse. The deeper failure was ideological arrogance. Western policymakers assumed that autocracies would liberalize as they enriched, that technology would empower citizens against authoritarians, and that economic interdependence would make war obsolete. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 shattered the last illusion. As The Economist observed, “The tank is back; so is great-power rivalry.”

The mechanisms that once integrated nations now divide them. Global trade, which surged from 39% of world GDP in 1990 to 60% by 2008, has plateaued and is increasingly fragmented into competing blocs. The U.S. and China are decoupling their technology ecosystems—semiconductors, artificial intelligence, telecommunications infrastructure—creating what some analysts call “parallel universes of innovation.” Energy, previously a force for interdependence, became a coercive tool when Russia weaponized gas supplies to Europe, triggering the worst energy crisis in generations.

Even information—the currency of the digital age—has become a battlefield. Russian disinformation campaigns, Chinese narrative control, and Western social media platforms’ struggle with content moderation have produced not a global conversation but a cacophony of incompatible realities. Democratic backsliding has accelerated, with Freedom House recording 17 consecutive years of declining global freedom.

What a Multipolar World Really Means

The term “multipolar world order” gets thrown around carelessly. It doesn’t simply mean multiple power centers—the world has always had regional powers. What’s emerging is something more complex and potentially more unstable: a system where no single nation can set rules, where coalitions are fluid and transactional, and where might increasingly makes right.

This new multipolarity has three defining features. First, variable geometry—countries align differently on different issues. India, for example, participates in the Quad (with the U.S., Japan, and Australia) to counter China but buys Russian oil and abstains on Ukraine votes at the UN. Saudi Arabia normalizes relations with Iran through Chinese mediation while maintaining security ties to Washington. These aren’t contradictions; they’re the new logic.

Second, institutional paralysis. The UN Security Council—designed for a different era—is structurally incapable of addressing today’s crises, with Russia holding a veto and China increasingly willing to use its own. The World Trade Organization hasn’t completed a major multilateral round since 1994. The Bretton Woods institutions remain dominated by Western voting shares that no longer reflect economic reality. As Foreign Affairs recently documented, “The gap between the problems we face and the institutions we have to solve them has never been wider.”

Third, the return of spheres of influence. Russia’s war in Ukraine is explicitly about denying neighboring states sovereign choice. China’s Belt and Road Initiative—spanning 150 countries and over $1 trillion in infrastructure investment—creates economic dependencies that translate into political leverage. The U.S. maintains its alliance network but increasingly frames security in zero-sum terms. We’re not heading toward a rules-based multipolar order; we’re already in a power-based one.

The global South isn’t choosing sides—it’s choosing interests. At the UN vote condemning Russia’s invasion, 35 countries abstained and 12 were absent, representing more than half the world’s population. These nations see Western calls for a “rules-based order” as selective, applied to adversaries but not allies, enforced in Ukraine but ignored in Gaza or Yemen. The credibility deficit is real.

The Weaponization of Interdependence

Globalization was supposed to make conflict costly. It did—but that hasn’t stopped states from wielding economic tools as weapons. We’re witnessing what scholars call “weaponized interdependence“: the strategic use of network positions in global systems to coerce or exclude rivals.

Start with semiconductors. Taiwan produces over 90% of the world’s most advanced chips, making it simultaneously indispensable and vulnerable. The U.S. has effectively banned Chinese access to cutting-edge chip-making equipment through export controls, while Beijing has restricted exports of rare earth minerals critical to defense and clean energy. These aren’t trade disputes; they’re preview skirmishes in a potential conflict over Taiwan.

Energy flows have become political levers. Europe’s dependence on Russian gas—which supplied 40% of its natural gas before the war—gave Moscow enormous coercive power. The subsequent pivot to liquified natural gas from the U.S. and Qatar demonstrates that diversification is possible, but costly and slow. Meanwhile, China has locked up long-term contracts for resources across Africa and Latin America, securing supply chains while Western powers scramble.

Financial architecture is fragmenting too. The U.S. and allies’ decision to freeze Russian central bank reserves and eject Russian banks from SWIFT demonstrated the dollar-based system’s weaponizability—but also accelerated efforts to bypass it. China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) is expanding, yuan-denominated oil contracts are growing, and discussions of BRICS currencies gained momentum at recent summits. The dollar’s dominance isn’t ending soon, but its primacy is no longer assumed to be permanent.

Data governance presents perhaps the most consequential battlefield. Should data flow freely across borders (the Western position) or remain subject to national sovereignty and storage requirements (the Chinese model)? Europe’s GDPR represents a third way, emphasizing privacy rights over either commercial freedom or state control. There’s no emerging consensus—only divergence.

Why 2026–2030 Is the Decisive Window

History accelerates in certain periods, when choices made reverberate for generations. The late 1940s were such a moment, producing the UN, Bretton Woods, NATO, and the Marshall Plan. The early 1990s were another, though the choices made then—NATO expansion, shock therapy economics, WTO accession without political reform—look less wise in hindsight.

We’re in a third such period. Several factors make the next four years critical for rebuilding global order.

First, leadership transitions. The 2024 U.S. election has produced a new administration taking office as this is written. European elections in 2024 shifted the European Parliament rightward. China’s leadership, while more stable, faces slowing growth and demographic decline that will force strategic choices. India’s emergence as a major power is accelerating, with elections that will shape its trajectory. These concurrent transitions create both risk and opportunity—the chance to reset relationships before they calcify into permanent hostility.

Second, technological inflection points. Artificial intelligence is advancing faster than governance frameworks can adapt. The next few years will determine whether AI development follows a cooperative model (sharing safety research, preventing autonomous weapons races) or a competitive one (national AI champions, digital authoritarianism, ungoverned deployment). Climate technology is reaching scale—solar and batteries are now often cheaper than fossil fuels—creating opportunities for collaborative energy transitions if countries can align incentives.

Third, institutional windows. The UN’s 80th anniversary in 2025 and various institutional reviews create political space for reforms that are impossible during normal times. The 2030 deadline for the Sustainable Development Goals imposes a timeline for global cooperation on development. The WTO’s ministerial conferences and climate COPs provide recurring venues where new frameworks could be negotiated.

Fourth, war fatigue. Ukraine’s war, while ongoing, has demonstrated to Russia and others the unsustainability of conquest in a mobilized, weaponized world. The economic costs of fragmentation are becoming clear—global growth is sluggish, inflation pressures persist, and supply chain vulnerabilities plague everyone. The pain creates incentives to find off-ramps, if leaders are wise enough to take them.

But the window won’t stay open. If the next four years produce further fragmentation—China invading Taiwan, a wider Middle East war, collapse of arms control—the possibility of reconstructing any global order will vanish. We’ll be fully in the realm of competing blocs and zero-sum competition.

Concrete Steps to Build a Resilient Global Order

Rebuilding can’t mean restoring American hegemony or even Western dominance. That ship has sailed. The question is whether it’s possible to construct a polycentric order—multiple centers of power operating within agreed frameworks that prevent catastrophic conflict and enable cooperation on shared challenges.

This requires both humility about what’s achievable and ambition about what’s necessary. Here’s a framework:

Reform Core Institutions to Reflect Reality

The UN Security Council’s permanent membership—decided in 1945—no longer reflects global power. Expansion is overdue, with seats for India, Brazil, and African representation in some form. This is diplomatically complex but necessary for legitimacy. The alternative is growing irrelevance.

The IMF and World Bank need governance changes that give rising economies voting shares commensurate with their economic weight. China has proposed reforms repeatedly; Western resistance makes these institutions look like relics of Western power rather than genuine multilateral forums.

The WTO needs restoration of its dispute settlement mechanism, paralyzed since 2019 when the U.S. blocked appellate body appointments. Trade rules require updating for digital commerce, state capitalism, and climate-related measures. If the WTO can’t adapt, trade will fragment into bilateral and regional deals, losing any multilateral character.

These reforms won’t happen easily. They require Western countries accepting reduced voting shares and influence in exchange for revitalized, legitimate institutions. That’s a hard domestic sell, but the alternative—irrelevant institutions and no frameworks at all—is worse.

Build Coalitions of the Capable

If universal agreements are impossible, work with those willing. This means plurilateral approaches—coalitions of countries that share specific interests, even if they don’t agree on everything.

On climate, for example, the U.S., EU, and China together account for over half of global emissions. A trilateral framework on technology sharing, carbon pricing, and transition finance could achieve more than endless COP negotiations seeking consensus among 190+ parties. Expanding this to include India, Japan, and major developing emitters could create sufficient critical mass.

On technology governance, democracies could coordinate on AI safety standards, semiconductor supply chain security, and data protection frameworks. This isn’t about excluding China completely—interoperability matters—but about setting standards that reflect democratic values and then inviting others to adopt them if they choose.

On nuclear arms control, the U.S. and Russia still possess 90% of the world’s nuclear weapons. Bilateral talks must resume, even amid broader hostility. China should be brought into arms control negotiations as its arsenal expands. The New START treaty’s 2026 expiration creates urgency.

Create Minilateral Security Architecture

NATO remains the world’s most capable alliance, but it can’t be the sole security framework for a multipolar world. The West needs additional security partnerships that aren’t about containing China but about regional stability.

The Quad (U.S., Japan, India, Australia) should deepen coordination on maritime security, disaster response, and infrastructure financing—offering alternatives to Chinese-dominated projects. AUKUS (Australia, UK, U.S.) provides a model for technology sharing among close partners. Similar frameworks could emerge in other regions.

Crucially, these arrangements should have thresholds for engagement with rivals. Regular military-to-military communications with China and Russia reduce accident risks. Hotlines and crisis management protocols prevent escalation. During the Cold War, the U.S. and USSR maintained communication channels even at the tensest moments. That wisdom applies today.

Develop Values-Based Tech Governance

Technology competition will define the 21st century, but it doesn’t have to be a race to the bottom. Democratic countries should coordinate on principles for AI development: transparency, human oversight, privacy protection, and limiting use in autonomous weapons.

The EU’s AI Act provides a foundation, establishing risk tiers and requirements for high-risk applications. The U.S., Japan, South Korea, and other democracies could align their approaches, creating a large market for responsible AI that sets effective global standards.

On critical infrastructure—semiconductors, telecommunications, cloud computing—selective decoupling from authoritarian rivals makes sense where genuine security risks exist. But this should be narrow and focused, not a new digital Iron Curtain. Maintaining scientific collaboration and academic exchange remains important even amid strategic competition.

Link Climate and Security

Climate change is a threat multiplier, worsening water scarcity, migration pressures, and resource conflicts. It’s also a rare area where cooperation serves everyone’s interests. The West should propose linking climate finance to security cooperation.

Specifically: major emitters (including China) contribute to a massively scaled-up climate adaptation fund for vulnerable countries, particularly in Africa and South Asia. In exchange, these countries receive support for governance and stability, reducing migration pressures and conflict risks that affect everyone.

China is already the largest bilateral lender to developing countries. The West should match or exceed this with transparent, sustainable financing tied to institutions rather than dependency. If the West can’t compete with China’s infrastructure investments, it loses influence across the global South.

Rebuild Democratic Credibility

None of this works if democracies can’t demonstrate that their system delivers better outcomes. That means addressing the domestic pathologies—polarization, inequality, institutional dysfunction—that have undermined Western credibility.

The U.S. needs to show it can still build infrastructure, regulate tech platforms, and provide healthcare and education at levels comparable to peer democracies. Europe needs to demonstrate it can defend itself and make timely decisions. The alternatives to democracy—Chinese authoritarianism, Russian nationalism—look appealing to some precisely because Western democracies appear sclerotic.

This isn’t altruism; it’s strategic necessity. A world where democracy looks like a failing system will be a world where autocrats gain adherents and confidence. Conversely, democracies that deliver prosperity and justice will attract partners and maintain legitimacy.

The Global South’s Role in the New Order

Any viable global order must account for the voices and interests of countries that make up the majority of humanity. The global South—roughly 85% of the world’s population—isn’t a monolith, but it shares some common perspectives that the West ignores at its peril.

First, a deep skepticism of Western lectures about rules-based order. Countries remember that the Iraq War violated international law, that Western banks caused the 2008 financial crisis with global repercussions, and that climate change was caused primarily by historical Western emissions that now-developing countries are asked to curtail.

Second, pragmatic non-alignment. Most countries want access to Chinese investment, Western technology, and Russian energy—whatever serves development goals. The Cold War–style “you’re either with us or against us” framing doesn’t work. India’s ability to maintain relations with all major powers while advancing its interests is increasingly the model others follow.

Third, demand for agency in global governance. African countries, representing 1.4 billion people, have no permanent Security Council seat. Latin America’s voices are marginalized in economic governance. The Middle East beyond Saudi Arabia and Israel is often treated as a problem to be managed rather than a region with its own agency and interests.

A rebuilt global order must offer the global South genuine partnership, not clientelism. That means:

- Development finance that competes with China’s Belt and Road on scale, not just rhetoric about transparency and debt sustainability (which matters but isn’t sufficient).

- Technology transfer on climate and health, not just intellectual property protection that keeps life-saving innovations expensive.

- Institutional voice through Security Council reform and reweighted voting in economic institutions.

- Respect for sovereignty and non-interference, which most of the global South values more highly than Western promotion of democratic norms.

The West can’t afford to write off the global South or assume it will choose autocracy over democracy. But earning their partnership requires acknowledging past failures and offering tangible benefits, not just moral arguments.

Managing the China Challenge Without Catastrophe

China presents the most complex challenge to any new global order. It’s simultaneously a rival, a partner on climate and trade, and a country whose choices will shape whether this century sees catastrophic conflict or managed competition.

The West’s approach should be competitive coexistence—neither the naive engagement of the 1990s nor the comprehensive confrontation that some advocate. This means:

Compete where interests genuinely clash. On technology supremacy, Taiwan’s security, and maritime disputes in the South China Sea, the West and its partners should maintain clear red lines backed by capability. Economic decoupling in sensitive sectors (advanced semiconductors, certain AI applications, defense-critical minerals) is justified.

Cooperate where interests align. Climate change, pandemic preparedness, nuclear non-proliferation, and space debris don’t respect national boundaries. Chinese solar panel production has dramatically lowered clean energy costs globally—that benefits everyone. Scientific research, particularly in basic science, should remain collaborative where possible.

Communicate constantly to prevent miscalculation. The most dangerous scenario isn’t intentional aggression but accidental escalation from Taiwan Strait incidents, cyberattacks, or economic crises. Military-to-military dialogues, leader-level summits, and track-two diplomacy should intensify, not diminish.

Model an alternative. The best response to China’s authoritarian state capitalism isn’t to copy it but to demonstrate that democratic systems can innovate faster, adapt more flexibly, and provide better lives for citizens. If that’s true, many countries will prefer the democratic model. If it’s not true, no amount of rhetoric will matter.

The Taiwan question remains the most dangerous flashpoint. Beijing has made reunification a core nationalist goal; Washington has committed to Taiwan’s defense. War would be catastrophic for all parties. The current status quo—strategic ambiguity, unofficial relations, robust arms sales—has kept peace for decades but looks increasingly fragile.

Maintaining it requires military deterrence sufficient to make an invasion too costly, diplomatic creativity to give Beijing off-ramps, and discipline to avoid symbolic gestures that provoke crises without enhancing security. That’s a tightrope, but it’s navigable with skill and patience.

The Case for Cautious Optimism

The picture painted so far is sobering. War in Europe, democratic backsliding, fragmenting trade, and nuclear-armed rivals with clashing visions. Why should anyone be optimistic that the West—or anyone—can build a new global order?

Because history shows that even amid catastrophe, humans have rebuilt. The institutions created after World War II emerged from even greater devastation. The Cold War ended without nuclear exchange despite decades of existential tension. The 2008 financial crisis, which seemed likely to trigger a depression, was managed through unprecedented cooperation.

More concretely, several trends favor reconstruction over collapse:

Nuclear weapons impose caution. No major power wants direct war with another nuclear state, which constrains escalation in ways that didn’t exist before 1945. Proxy conflicts and economic warfare are awful, but they’re preferable to great power war.

Economic interdependence, while weaponized, remains deep. China and the U.S. trade over $750 billion annually. Complete decoupling would devastate both economies and many others. That creates incentives—grudging, perhaps, but real—for managing competition.

Climate imperatives force cooperation. No country can solve climate change alone. The physics doesn’t care about ideology. As damages mount—from flooding to food insecurity to migration—cooperation on mitigation and adaptation becomes survival, not idealism.

Democratic resilience shouldn’t be underestimated. Yes, democracies face challenges, but they’ve adapted before. The expansion of voting rights, welfare states, civil rights movements—all were responses to crises that made democracies more inclusive and legitimate. Current challenges could spur similar evolution.

Younger generations globally share values around climate action, social justice, and skepticism of nationalism that could reshape politics. Youth voter participation is rising, and while young people’s views are diverse, they’re generally more internationalist and less ideological than older cohorts.

The optimism must be cautious because the path is narrow and failure is possible. But it’s not inevitable.

A Call to Action: What Leaders Must Do Now

Rebuilding global order requires specific actions from those with power to shape it:

U.S. leaders must recognize that hegemony is over but leadership remains possible. That means investing in alliances, accepting institutional reforms that reduce American voting shares, and demonstrating that democracy can still deliver prosperity. It means restraining the impulse toward unilateralism and accepting that multilateralism is sometimes slower but more sustainable.

European leaders must move beyond dependence—on American security guarantees, on Russian energy, on Chinese manufacturing. That means defense spending that allows genuine strategic autonomy, industrial policy that secures critical supply chains, and diplomatic initiative that makes Europe a pole in multipolarity, not a prize to be competed over.

Chinese leaders face a choice between seeking dominance (which will provoke lasting opposition) and accepting shared leadership in a multipolar system. The latter would require transparency about military capabilities, compromise on territorial disputes, and trade practices that don’t systematically disadvantage partners. It’s unclear whether China’s political system can make these choices, but the offer should be extended.

Global South leaders should leverage their position. Non-alignment gives power when major powers compete for partnership. But it also requires making affirmative choices about what kind of order serves their interests, not just playing great powers against each other opportunistically.

Citizens in democracies must hold leaders accountable for both vision and delivery. That means demanding foreign policy that balances idealism with realism, rejecting both isolationism and overextension, and supporting the resources—diplomatic, military, economic—required to sustain global engagement.

The next four years will determine whether the 21st century becomes an era of spheres of influence and recurring crises or a period of managed multipolarity with functional cooperation on existential challenges. The West can’t unilaterally decide this outcome, but it can make the choice between constructive adaptation and nostalgic decline.

This is, genuinely, the last chance. Not because the West will disappear—it won’t—but because the window for shaping a new global order is closing. The decisions made between now and 2030 will echo for decades, perhaps generations. The world has changed more in the past four years than in the previous thirty. The next four will change it even more.

The question is whether we’ll navigate that change with wisdom, building institutions and partnerships that prevent the worst while enabling cooperation on shared challenges—or whether we’ll drift into fragmentation, conflict, and a darker future that none of us wants but all of us might get if we’re not careful.

The foundations are crumbling. We can rebuild them, but only if we start now, work together, and accept that the new architecture must look different from the old. The alternative isn’t stasis; it’s collapse. That’s why this is the West’s last chance—and humanity’s best hope.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

Digital Economy as Pakistan’s Next Economic Doctrine: A Growth Debate Trapped in the Past

Understanding the Digital Economy: More Than a Sector, a System

There is a persistent category error at the heart of Pakistan’s economic policymaking. Officials speak of the “digital economy” the way an earlier generation spoke of textiles or agriculture — as a discrete sector, a line on an export ledger, a portfolio to be managed rather than a platform to be built. This confusion is not merely semantic. It shapes budget allocations, regulatory frameworks, institutional mandates, and, ultimately, the trajectory of a nation of 240 million people standing at a crossroads between chronic underdevelopment and a genuinely plausible economic transformation.

The digital economy, properly understood, is not a sector. It is the operating system upon which all modern economic activity increasingly runs. It encompasses the digitisation of production processes, the datafication of consumer behaviour, the platformisation of labour markets, and the emergence of knowledge as the primary factor of production. When the World Bank’s April 2025 Pakistan Development Update frames digital transformation as Pakistan’s most credible path toward export competitiveness and sustained growth, it is not advocating for a bigger IT park in Islamabad. It is arguing for a wholesale reimagining of what the Pakistani economy produces, and for whom.

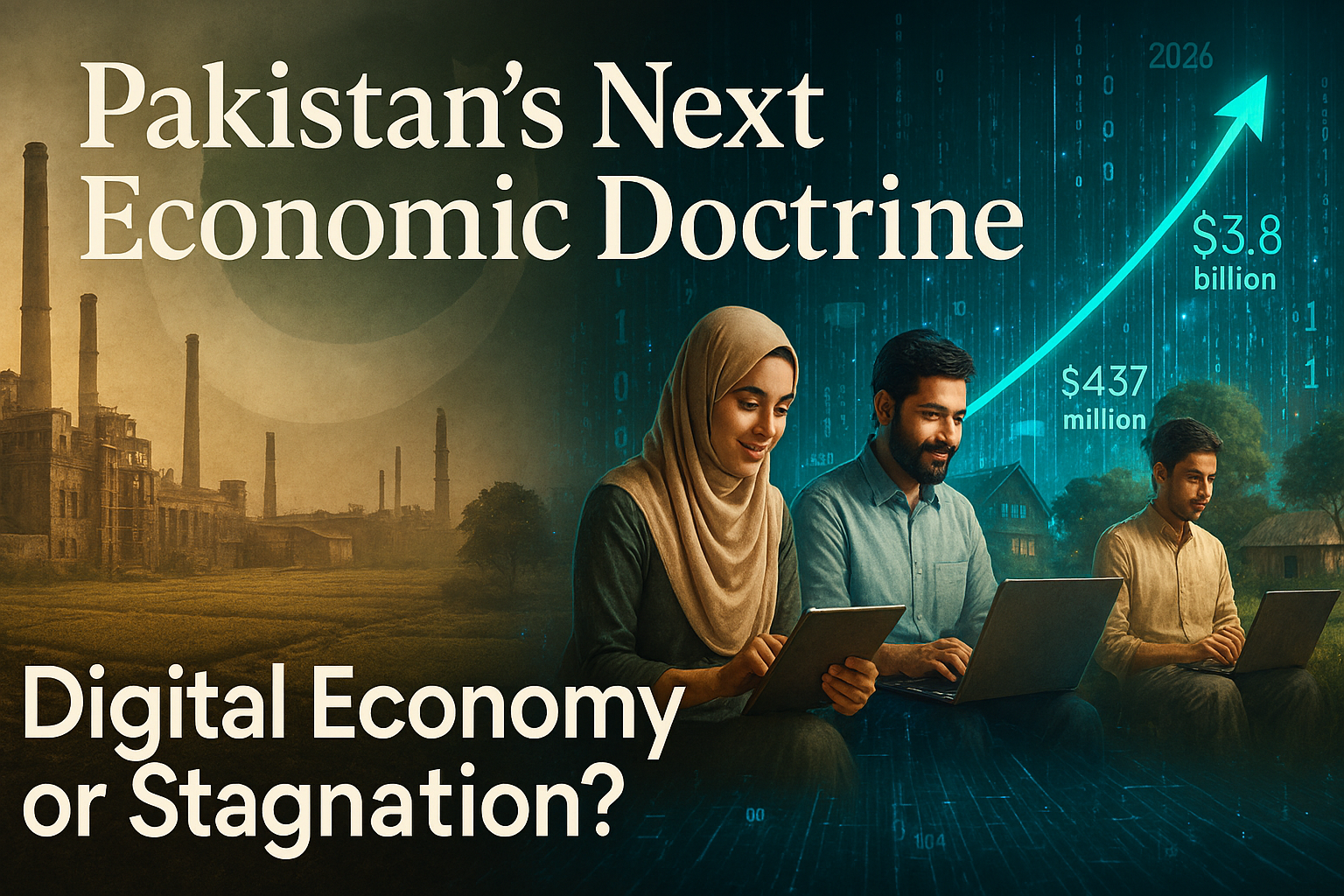

That reimagining has begun — tentatively, unevenly, and against considerable institutional resistance. The numbers, for once, are genuinely exciting. Pakistan IT exports reached $3.8 billion in FY2024–25, with the momentum building sharply into the current fiscal year: $2.61 billion in IT and ICT exports were recorded between July and January of FY2025–26, a 19.78% increase year-on-year, according to data released by the Pakistan Software Export Board (PSEB). December 2025 delivered a record single-month figure of $437 million — the highest in the country’s history. These are not marginal gains. They are signals of structural potential.

The question this analysis addresses is whether Pakistan possesses the institutional architecture, policy coherence, and political will to convert those signals into doctrine — or whether it will allow a historic opportunity to dissolve into the familiar entropy of short-termism, infrastructure neglect, and regulatory dysfunction.

Pakistan’s Emerging Digital Base: A Foundation That Defies the Headlines

The pessimistic narrative about Pakistan — fiscal crisis, security fragility, political instability — dominates international discourse and obscures a digital demographic reality that is, by most comparative metrics, extraordinary. Pakistan now has 116 million internet users, with penetration reaching 45.7% in early 2025 and accelerating. The PBS Household Survey 2024–25 found that over 70% of households have at least one member online, with individual usage approaching 57% of the adult population. Against the baseline of five years ago, this represents a compression of the connectivity timeline that took wealthier economies a generation to traverse.

Mobile is the primary vector. Pakistan’s 190 million mobile connections and 142 million broadband subscribers — figures corroborated by GSMA’s State of Mobile Internet Connectivity — reflect a population that has leapfrogged fixed-line infrastructure entirely and gone straight to smartphone-mediated internet access. Smartphone ownership has surged with the proliferation of affordable Chinese handsets, democratising access in a way that no government programme could have engineered.

The identity infrastructure is strengthening in parallel. NADRA’s digital ID system now covers the vast majority of the adult population, providing the authentication backbone without which digital financial services, e-commerce, and government-to-citizen digital delivery cannot scale. The State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) digital payments architecture — including the Raast instant payment system — has facilitated a measurable shift in transaction behaviour, particularly among younger urban cohorts.

What Pakistan has, in other words, is a digital base: not yet a digital economy, but the preconditions for one. The distinction is critical. A digital base is necessary but not sufficient. Converting it into export-generating, job-creating, productivity-enhancing economic activity requires deliberate policy architecture — something Pakistan has so far delivered only in fragments.

Geography Is Being Rewritten: The Location Dividend

For most of economic history, geography was fate. A landlocked country, a country far from major shipping lanes, a country without navigable rivers or natural harbours faced structural disadvantages that compounded over centuries. Pakistan’s geographic position — bordering Afghanistan, Iran, India, and China, with access to the Arabian Sea — has historically been as much a source of strategic anxiety as economic opportunity.

The digital economy rewrites this calculus. In knowledge-intensive digital services, physical location is increasingly irrelevant to market access. A software engineer in Lahore can serve a fintech client in Frankfurt. A data scientist in Karachi can work for a healthcare analytics firm in Houston. A UX designer in Peshawar can deliver to a product team in Singapore. The barriers that historically constrained Pakistani talent to domestic labour markets — or forced emigration — are structurally dissolving.

This is the location dividend: the ability to monetise Pakistani human capital in global markets without the friction costs of physical migration. It is a form of comparative advantage that requires no natural resources, no preferential trade agreements, and no proximity to wealthy consumer markets. It requires only talent, connectivity, and institutional conditions that allow value to flow across borders.

Pakistan’s digital economy growth model, at its most ambitious, is predicated on precisely this arbitrage: world-class technical skill delivered at emerging-market cost, routed through digital platforms, and paid in foreign exchange. The macroeconomic implications — for the current account, for foreign reserves, for wage convergence — are profound. The World Bank’s Digital Pakistan: Economic Policy for Export Competitiveness report identifies this services export channel as among the most scalable dimensions of the country’s growth potential.

The geography dividend is real. The question is whether Pakistan can build the institutional infrastructure to fully claim it.

The Freelancer Paradox: Scale Without Structure

Perhaps nowhere is the tension between Pakistan’s digital potential and its institutional constraints more vividly illustrated than in its freelance economy. The headline numbers are startling. Pakistan’s 2.37 million freelancers — an estimate from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) — generate a scale of digital services exports that places the country consistently in the top three to four globally on platforms including Upwork, Fiverr, and Toptal. Freelance earnings in H1 FY2025–26 reached $557 million, a 58% year-on-year increase from $352 million — a growth rate that no traditional export sector can approach.

This is the “freelancer paradox Pakistan” faces: enormous revealed comparative advantage, operating almost entirely outside formal policy architecture. The vast majority of Pakistan’s freelancers work without contracts, without access to institutional credit, without social protection, and without the kind of professional certification or dispute resolution frameworks that would allow them to move up the value chain from commodity task completion to complex, high-margin engagements.

The income ceiling is real and consequential. A Pakistani freelancer completing logo designs or basic data entry tasks on Fiverr earns at the low end of the global digital labour market. The same talent, operating through a structured agency model, with portfolio development support, client management training, and access to premium platforms, could command rates three to five times higher. The gap between what Pakistan’s freelance workforce earns and what it could earn is, effectively, a measure of what institutional neglect costs.

The foreign exchange dimension compounds the problem. Payments routed through platforms like PayPal — where availability for Pakistani users remains restricted — or through informal hawala networks, often bypass the formal banking system entirely. The SBP has made progress in facilitating formal remittance channels, but significant friction remains. Pakistan freelance exports are growing despite the system, not because of it.

A comprehensive Pakistan digital economy doctrine must address the freelancer economy not as an afterthought but as a strategic asset requiring dedicated institutional support: access to formal banking, skills certification, contract facilitation, and platform-level advocacy.

Infrastructure Reliability as Export Competitiveness: The Invisible Tax

Ask any Pakistani software engineer working on an international client project what their single biggest operational constraint is, and the answer is rarely regulatory. It is the power cut that interrupted a client call. It is the bandwidth throttling that corrupted a code repository push. It is the VPN restriction that prevented access to a cloud development environment. These are not edge cases. They are the daily texture of doing business in Pakistan’s digital economy.

Infrastructure reliability is not a background variable. In digital services exports, it is export competitiveness. A Pakistani IT firm competing against Indian, Ukrainian, or Filipino counterparts is not merely selling talent — it is selling reliable, on-time, high-quality delivery. A single missed deadline caused by a grid outage can cost a client relationship worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Cumulatively, infrastructure unreliability functions as an invisible tax on Pakistan’s digital exports Pakistan is uniquely ill-positioned to afford.

The electricity crisis is the most acute dimension of this problem. Pakistan’s circular debt overhang — exceeding Rs. 2.4 trillion — continues to produce load-shedding that falls hardest on small businesses and home-based workers, who constitute the backbone of the freelance and micro-enterprise digital economy. Large IT firms in tech parks have access to backup generation; individual freelancers in Multan or Faisalabad do not.

Broadband quality is the second constraint. Pakistan’s average fixed broadband speed, while improving, remains well below regional competitors. Mobile data costs have declined, but network congestion in urban cores during peak hours frequently degrades the quality of experience to levels incompatible with professional digital work. The GSMA has consistently highlighted last-mile connectivity gaps as the primary barrier to realising Pakistan’s mobile internet dividend.

A credible Pakistan digital economy doctrine must treat infrastructure investment — in power stability, fibre optic expansion, and spectrum management — not as a public works programme but as export infrastructure, directly analogous to port expansion for goods trade.

Cyber Risks and the Trust Deficit: The Hidden Vulnerability

Digital economies are only as robust as the trust that underpins them. Trust operates at multiple levels: consumer trust in digital financial services, business trust in cloud infrastructure, investor trust in data governance frameworks, and international partner trust in Pakistan’s regulatory environment. On all of these dimensions, Pakistan faces a significant trust deficit that constrains the Pakistan digital economy growth trajectory.

Cybersecurity incidents affecting Pakistani financial institutions have multiplied. The banking sector has faced card data breaches, phishing campaigns targeting mobile banking users, and SIM-swap fraud at scale. The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority’s (PTA) record of internet shutdowns and platform restrictions — including prolonged access restrictions to major social media platforms during periods of political tension — has created a perception among international digital businesses that Pakistan’s internet governance is unpredictable.

This unpredictability carries a direct economic cost. International clients contracting Pakistani firms for sensitive data processing work — healthcare records, financial data, personal information — conduct due diligence on the regulatory and security environment. A country with a history of arbitrary platform restrictions and limited data protection enforcement does not inspire confidence for high-value data contracts.

Pakistan’s Personal Data Protection Bill, in legislative limbo for several years, represents the most visible symptom of this institutional gap. Without a credible, enforced data protection framework, Pakistan cannot credibly bid for the categories of digital services work — cloud processing, AI training data, health informatics — where the highest margins and fastest growth lie. Closing this gap is not merely a legal formality; it is a prerequisite for moving up the digital value chain.

Institutional Constraints and Policy Incoherence: The Structural Brake

Pakistan’s digital economy governance is fragmented across a proliferation of bodies — the Ministry of IT and Telecom (MoITT), PSEB, PTA, the National Information Technology Board (NITB), provincial ICT authorities, and the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) — with overlapping mandates, inconsistent coordination, and chronic under-resourcing. This fragmentation is not accidental; it reflects the accumulation of institutional layering that characterises Pakistan’s economic governance more broadly.

The policy incoherence is manifested in contradictions that would be almost comic if they were not so economically costly. Pakistan simultaneously promotes itself as a top destination for IT outsourcing while maintaining VPN restrictions that its own IT workers require to access client systems. It celebrates freelance export earnings while allowing the forex payment infrastructure for those earnings to remain dysfunctional. It announces ambitious digital skills programmes while underfunding the higher education institutions that produce the graduates those programmes are supposed to train.

The Pakistan IT exports 2026 growth trajectory — impressive as it is — is occurring largely in spite of, rather than because of, this governance architecture. The question for policymakers is not whether the current momentum can continue; it can, for a time, on the basis of demographic dividend and individual entrepreneurial energy alone. The question is whether that momentum can be compounded into the kind of structural transformation that moves Pakistan from an exporter of digital labour to an exporter of digital products and platforms.

That transition requires a qualitatively different institutional environment: one capable of regulating without strangling, facilitating without distorting, and investing at the horizon of a decade rather than the cycle of a fiscal year.

Digital Sovereignty and Platform Dependency: The Strategic Dimension

Beneath the growth narrative lies a geopolitical and strategic question that Pakistan’s digital economy debate has been slow to engage: the question of digital sovereignty Pakistan must navigate. As Pakistani businesses and individual workers increasingly integrate into global digital platform ecosystems — Upwork, Fiverr, AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure — they gain access to markets, infrastructure, and tools that would be impossible to replicate domestically. They also incur structural dependencies that carry long-term risks.

Platform dependency is not a uniquely Pakistani problem. Every country that has embraced the global digital economy faces some version of this tension. But for Pakistan, the risks are heightened by the country’s limited regulatory leverage, its absence from the standard-setting bodies that govern international digital trade, and the concentration of critical digital infrastructure in the hands of a small number of US-headquartered technology corporations.

The practical implications are significant. When a major freelance platform adjusts its fee structure or payment policies, Pakistani freelancers — who have no collective bargaining mechanism, no government-backed alternative platform, and no domestic digital marketplace of comparable scale — absorb the consequences. When a cloud provider raises prices or discontinues a service, Pakistani startups that have built their infrastructure on that provider face switching costs that can be existential.

Digital sovereignty does not mean autarky. It means building sufficient domestic digital capacity — in cloud infrastructure, in payment systems, in data storage, in platform development — to maintain meaningful optionality. It means participating in the governance of the global digital economy rather than passively receiving its terms. It means developing the regulatory expertise to negotiate with platform giants on terms that protect Pakistani economic interests.

This is a long-game strategic agenda, not a short-cycle policy fix. But without it, Pakistan’s Pakistan digital economy growth risks being permanently extractive — generating value that is captured elsewhere.

Government as Digital Market Creator: The Enabling State

One of the most durable insights from the comparative study of digital economy development — South Korea, Estonia, Singapore, Rwanda — is that the private sector alone does not build digital economies. Governments create the conditions: the infrastructure, the standards, the skills pipeline, the procurement signals, and the regulatory certainty without which private investment cannot take root at scale.

Pakistan’s government has the opportunity — and, given the fiscal constraints, the obligation — to be a strategic market creator rather than a passive regulator. Government digitalisation is not merely an efficiency play; it is a demand-side signal to the domestic digital industry. When the government digitises land records, health systems, tax administration, and public procurement, it creates contract opportunities for Pakistani IT firms, validates the commercial viability of digital solutions, and builds the reference clients that domestic companies need to compete internationally.

The PSEB’s facilitation role — connecting international clients with Pakistani IT firms, providing export certification, and advocating for payment infrastructure improvements — represents the embryo of a more active industrial policy. The SIFC’s mandate, if properly operationalised for the digital sector, could provide the high-level coordination that has been missing. But these institutions need resources, autonomy, and political backing to function at the scale the opportunity demands.

The most immediate lever available is public digital procurement: a committed pipeline of government IT contracts awarded to domestic firms under transparent, merit-based processes. This single policy — properly designed and consistently executed — could do more to develop Pakistan’s digital industry than any number of incubator programmes or innovation fund announcements.

From Factor-Driven to Knowledge-Driven Economy Pakistan: The Structural Leap

Pakistan’s economic growth model has, for most of its history, been factor-driven: growth generated by deploying more labour, more land, more capital, in sectors with relatively low productivity — agriculture, low-complexity manufacturing, commodity exports. The digital economy represents the most credible pathway to a fundamentally different model: one in which growth is driven by increasing productivity, accumulating human capital, and generating returns from knowledge rather than from raw inputs.

The knowledge-driven economy Pakistan needs is not a distant aspiration. The ingredients exist, in nascent form: a young population with demonstrated aptitude for digital skills, universities producing engineers and computer scientists at scale, a diaspora with global networks and capital, and a domestic entrepreneurial ecosystem generating startups in fintech, healthtech, agritech, and edtech that are beginning to attract international venture investment.

The transition from factor-driven to knowledge-driven growth is not automatic or inevitable. It requires deliberate investment in research and development, in higher education quality, in intellectual property protection, and in the kind of long-term institutional stability that allows firms to make multi-year investment commitments. Pakistan’s R&D expenditure as a share of GDP remains among the lowest in Asia — a structural constraint that no amount of IT export promotion can overcome if sustained.

The ADB’s research on Pakistan freelancers earnings and digital service exports consistently emphasises that the earnings ceiling for task-based freelance work is far lower than for product-based or IP-based digital exports. Moving Pakistani digital workers up this value curve — from executing tasks to building products, from selling hours to licensing software — is the central challenge of knowledge economy transition.

Policy Priorities for a Digital Doctrine: What Must Be Done

A credible Pakistan digital economy doctrine for the period to 2030 requires six interlocking policy commitments, each necessary but none sufficient in isolation.

First, infrastructure as export policy. Pakistan must treat reliable electricity supply and high-quality broadband as preconditions for digital export competitiveness, not as welfare goods. This means prioritising digital economic zones with guaranteed power supply, accelerating fibre optic backbone expansion into secondary cities, and reducing spectrum costs for business-grade mobile broadband.

Second, the forex plumbing must be fixed. The SBP must complete the liberalisation of digital payment channels, enabling Pakistani freelancers and digital firms to receive, hold, and deploy foreign currency earnings without the friction that currently drives significant volumes into informal channels. Every dollar that flows through informal networks is a dollar that does not build Pakistan’s foreign reserves or generate formal tax revenue.

Third, data protection legislation must be enacted and enforced. The Personal Data Protection Bill must be passed in a form that meets international standards — not as a regulatory box-ticking exercise, but as a genuine market access instrument. Pakistan cannot compete for high-value data services contracts without credible data governance.

Fourth, skills investment must match ambition. Pakistan’s Pakistan IT exports 2026 targets require a quantum expansion of the technical skills pipeline — not through low-quality short courses, but through sustained investment in computer science education at the tertiary level, curriculum modernisation, and industry-academia partnerships that ensure graduates enter the workforce with market-relevant capabilities.

Fifth, institutional consolidation. The fragmented governance architecture for the digital economy must be rationalised. A single, adequately resourced Digital Economy Authority — with a clear mandate, cross-ministerial coordination powers, and direct accountability to the Prime Minister — would reduce the transaction costs of doing business in Pakistan’s digital sector by orders of magnitude.

Sixth, a digital sovereignty strategy. Pakistan needs a national cloud strategy, a digital platform policy, and active participation in international digital trade negotiations. These are not luxury items for a mature digital economy; they are foundational choices that, once deferred, become progressively more expensive to make.

Conclusion: A Decisive Economic Choice

Pakistan’s Pakistan digital economy moment is real, and it is now. The combination of demographic scale, demonstrated digital talent, accelerating connectivity, and record IT and freelance export earnings constitutes a rare convergence of factors that, in other economies, has served as the launching pad for durable structural transformation.

But potential is not destiny. History is littered with countries that glimpsed the digital transformation horizon and then allowed institutional inertia, political short-termism, and infrastructure neglect to ensure they never reached it.

The debate Pakistan is currently having about its digital economy is, at its deepest level, a debate about what kind of economic future the country chooses to construct. The old paradigm — commodity exports, remittances, periodic IMF bailouts, growth that barely keeps pace with population — has delivered recurrent crisis and chronic underinvestment in human capital. The digital paradigm offers something genuinely different: a pathway to prosperity grounded in the one resource Pakistan has in abundance, its people, and their capacity for knowledge work in a globally connected economy.

Digital sovereignty Pakistan must claim is not merely about technology. It is about economic agency — the ability to participate in the global economy on terms that capture value domestically rather than exporting it. Every reform deferred, every institutional bottleneck left unaddressed, every dollar that flows through informal channels rather than the formal banking system, is a cost Pakistan cannot afford.

The choice between a Pakistan whose digital economy remains a promising footnote and one whose Pakistan digital economy growth becomes the defining story of the coming decade is not a technical question. It is a political one. And it must be answered decisively — before the window that demographics, technology, and global market demand have opened begins, once again, to close.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

KOSPI Record Crash: South Korea’s Stock Market Suffers Its Worst Day in History as the US-Iran War Detonates a Global Sell-Off

At 9:03 a.m. Korean Standard Time, the screens inside the Korea Exchange trading hall in Yeouido, Seoul, turned a uniform, searing red. Within minutes, the sell orders were not arriving in waves — they were arriving like a flood breaking through a dam. Algorithms fired. Margin calls cascaded. Retail investors, who only weeks ago were borrowing money to buy Samsung Electronics at record highs, watched years of gains dissolve in real time. By 9:17 a.m., trading had been suspended for twenty minutes: the circuit breaker, a mechanism designed for exactly this kind of controlled catastrophe, had triggered for just the seventh time in the KOSPI’s 43-year history.

By the closing bell, South Korea’s benchmark index had shed 12.06 percent — 698.37 points — to close at 5,093.54. It was the worst single day in the KOSPI’s recorded history, surpassing even the paralysing shock of September 11, 2001. The world’s hottest major stock market, up more than 40 percent in just two months, had just been broken — not by a domestic crisis, not by a company scandal, but by missiles fired 6,000 kilometres away in the Persian Gulf.

What Happened: A Minute-by-Minute Collapse

The trigger was a week in the making. On the morning of February 28, 2026, US and Israeli forces launched a coordinated series of airstrikes against Iran, an operation that reportedly included the assassination of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. Iran’s response was swift and economically calculated: the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps announced a closure of the Strait of Hormuz, the narrow chokepoint through which roughly 20 million barrels of crude oil transit daily — accounting for approximately 20 percent of global supply.

South Korean markets were closed on Monday, March 2, for Independence Movement Day. When trading reopened Tuesday morning, the pent-up global selling pressure — two full days of deteriorating sentiment compressed into a single session — hit simultaneously. The KOSPI fell 7.24 percent on Tuesday, closing at 5,791.91, its largest single-session point drop on record at that time.

Wednesday brought something far worse.

The timeline:

- 09:00 KST — KOSPI opens at 5,592.29, already down sharply from Tuesday’s close.

- 09:08 KST — Circuit breaker triggered on the KOSDAQ after losses exceed 8 percent; trading suspended 20 minutes.

- 09:14 KST — KRX activates sidecar mechanism on the KOSPI as sell orders overwhelm buy-side liquidity.

- 09:17 KST — KOSPI circuit breaker fires. At the time of the halt, the index is down 469.75 points — 8.11 percent — to 5,322.16.

- 09:37 KST — Trading resumes. Selling immediately intensifies.

- 11:20 KST — KOSPI reaches intraday low of 5,059.45, down 12.65 percent — the worst intraday reading in 25 years and 11 months.

- 15:30 KST — Official close: 5,093.54, down 12.06 percent. Of the more than 800 stocks on the benchmark, just 10 finish in the green.

The KOSDAQ, South Korea’s technology-heavy secondary index, fared even worse, closing down 14 percent at 978.44 — its largest single-day decline since its founding in January 1997. The combined two-day equity wipeout erased an estimated $430 billion in market value.

Why South Korea Was Hit Hardest: The Anatomy of a Perfect Storm

Every major economy felt the tremor of the Iran conflict on March 4. But none — not Japan, not Taiwan, not China — fell anything close to what Seoul experienced. The gap is not coincidental. It is structural.

Energy dependence, extreme and existential. South Korea imports approximately 98 percent of its fossil fuels, with around 70 percent of its crude oil sourced from the Middle East, much of it transiting the Strait of Hormuz. According to the US Energy Information Administration, South Korea ranks among the top importers of Hormuz-transit crude globally. When Iran threatened to close — and partially did close — that chokepoint, the calculus for Korean manufacturers and energy utilities changed instantly. Higher oil does not merely raise input costs; it compresses margins across the entire export-driven economy, stokes inflation, and pressures the current account. Nomura estimates that South Korea’s net oil imports represent 2.7 percent of GDP — among the highest of any major economy and a stark vulnerability flag in any energy shock scenario.

Semiconductor concentration, a double-edged sword. The KOSPI’s extraordinary 2026 rally — up more than 40 percent in the first two months of the year, touching an all-time high above 6,347 in late February — was almost entirely the story of two companies: Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix. Together, the two memory chip giants account for close to 50 percent of the index by market capitalisation, according to Morningstar equity research. When sentiment turned, that concentration did not merely reflect the market’s decline — it amplified it. Samsung Electronics fell 11.74 percent to 172,200 won. SK Hynix dropped 9.58 percent to 849,000 won. Hyundai Motor collapsed 15.80 percent. Kia Corp shed 13.82 percent. Shipping stocks Pan Ocean, HMM, and KSS Line — directly exposed to Hormuz route disruption — plunged between 16 and 19 percent.

As Lorraine Tan, Asia director of equity research at Morningstar, noted, “The decline in the KOSPI can broadly be attributable to the single-name concentration that we see in Korean markets.” She added that the drop also implied growing concern that AI data-centre adoption could slow due to significantly higher energy costs — a double hit for chips stocks caught between geopolitical risk and demand uncertainty.

Margin debt: the accelerant. Before the conflict erupted, South Korean retail investors had borrowed heavily to ride the bull market. Margin debt and broker deposits had surged to record highs. When prices began to fall, those leveraged positions triggered forced liquidations, turning an orderly retreat into a rout. “There’s been a lot of buying on credit, especially in the heavyweight stocks,” Kim Dojoon, chief executive of Zian Investment Management, told Bloomberg. “If there’s another drop on Thursday, nobody will catch a falling knife.”

The holiday amplifier. Monday’s market closure meant that South Korean markets absorbed two full days of global deterioration in a single session on Tuesday — and then suffered a second cascading wave on Wednesday, with no circuit of relief between them.

Historical Benchmark: Into Uncharted Territory

To understand the magnitude of what happened in Seoul on March 4, 2026, consider the events it eclipses.

The KOSPI has recorded a decline of 10 percent or more in a single session on only four occasions in its 43-year history. According to the Korea Herald and historical KRX data, those occasions are:

| Date | Event | KOSPI Decline |

|---|---|---|

| April 17, 2000 | Dot-com bubble peak | -11.63% |

| September 12, 2001 | Post-9/11 shock | -12.02% |

| October 24, 2008 | Global Financial Crisis | -10.57% |

| March 4, 2026 | US-Iran War | -12.06% |

The September 12, 2001 session had stood for nearly 25 years as the single worst day in South Korean market history — a day when global commerce froze and the world reoriented around fear. Wednesday’s close eclipsed it by a margin of 0.04 percentage points. The intraday low — 12.65 percent — was the deepest since April 17, 2000.

The KOSDAQ’s 14 percent plunge, meanwhile, surpassed its previous worst session: the 11.71 percent rout of March 19, 2020, at the nadir of the COVID-19 pandemic panic. What happened this week in Seoul did not merely set a record. It rewrote the category entirely.

What makes the comparison to 2001 particularly sobering is context. On September 12, 2001, markets around the world fell together. In 2026, Wall Street is barely flinching: the S&P 500 fell approximately 1 percent overnight. The KOSPI’s collapse is not a global synchronised shock — it is something more targeted, and in some ways more alarming: a geopolitical vulnerability unique to South Korea’s economic structure being stress-tested in real time.

Global Contagion: Oil, Currencies, and the Hormuz Premium

Seoul was the epicentre, but the aftershocks radiated across the region and beyond.

Oil. Brent crude surged 10–13 percent in the days following the initial strikes, trading around $80–82 per barrel by March 2–4, according to energy analysts cited by Reuters. Analysts warned that if the Hormuz disruption proves sustained, prices could breach $100 per barrel — a level that would add an estimated 0.8 percentage points to global inflation, according to projections cited in the economic impact assessment published by Wikipedia. Natural gas prices in Europe surged 38 percent following reported attacks on Qatari LNG export facilities.

The Korean won. The currency markets told the same story in different decimal places. The won briefly pierced 1,500 per dollar on Wednesday — a level not seen since March 10, 2009, at the nadir of the global financial crisis. It was, psychologically, an enormous threshold. Yan Wang, chief of emerging markets at Alpine Macro, told the Korea Herald that the Korean won is historically “one of the most sensitive emerging market currencies to global risk sentiment,” while cautioning that fundamentals do not justify such weakness unless the conflict drags on significantly.

Asian markets. The contagion spread, though nowhere matched Seoul’s severity:

- Japan Nikkei 225: -3.61% to 54,245.54

- Taiwan TAIEX: -4.40% to 32,829

- Hong Kong Hang Seng: -2.00% to 25,249.48

- Shanghai Composite: -1.00% to 4,082.47

The asymmetry is instructive. China, a major oil importer, absorbed the shock with relative composure — partly due to its diversified energy sourcing and partially because domestic policy responses appeared pre-positioned. Japan and Taiwan, similarly dependent on Middle East energy, fell meaningfully but remained far above Korean levels, their indices lacking the same speculative leverage overhang.

Travel and supply chains. Iran’s airspace was closed to civilian aircraft following the initial strikes on February 28. Multiple carriers suspended Middle East routes, with knock-on effects for travel and tourism across the Gulf. Shipping insurance costs for Hormuz-transit tankers surged, with analysts suggesting the “war premium” could add $5–15 per barrel to delivered oil costs regardless of military escort arrangements — a persistent, structural cost increase for energy importers like South Korea.

Three Scenarios: What Comes Next

The trajectory of South Korea’s markets now depends almost entirely on one variable: how long the conflict lasts, and whether the Strait of Hormuz reopens to normal commercial traffic.

Scenario 1 — Rapid Resolution (probability: 30%) The US achieves its stated military objectives within four to five weeks, as President Trump publicly signalled. Iranian counter-retaliation is contained. Oil retreats to sub-$80. In this scenario, the structural case for Korean equities reasserts itself quickly — AI memory demand remains intact, Samsung and SK Hynix resume margin expansion, and the KOSPI, still up approximately 21 percent year-to-date even after the crash, stages a sharp technical rebound. Forced liquidations reverse. Analysts at Seoul-based brokerages place a 10 percent rebound in the first week post-ceasefire as the base case for this outcome.

Scenario 2 — Prolonged Stalemate (probability: 50%) The conflict extends beyond one month. The Strait of Hormuz remains partially disrupted. Oil stabilises in the $85–95 range. South Korea’s current account balance deteriorates. The Bank of Korea is forced to weigh currency intervention against inflation pressures — a familiar but painful dilemma for an open economy. The KOSPI finds a floor in the 4,800–5,000 range as earnings revisions bite. Recovery is slow, uneven, and dependent on semiconductor demand holding firm even as energy costs rise. Foreign investors remain cautious.

Scenario 3 — Full Energy Shock (probability: 20%) The conflict escalates into a sustained regional war. Hormuz closes effectively for multiple months. Crude reaches $100 or beyond. In this scenario, Hyundai Research Institute’s earlier estimate — that sustained $100 crude could shave 0.3 percentage points from South Korea’s 2026 GDP growth — becomes conservative. The KOSPI potentially tests 4,000. The Bank of Korea is forced into emergency rate decisions. The IMF revises Asian growth projections downward across the board. Global stagflation risks — higher energy prices coinciding with slower growth — re-enter the policy conversation for the first time since 2022.

Investor Playbook and Policy Response

What regulators and institutions are doing. The Bank of Korea issued a statement vowing to “respond to herd-like behaviour” in financial markets and pledged liquidity support measures if volatility persisted. The Korea Exchange activated circuit breakers and sidecar mechanisms as designed, but market participants noted that the tools slowed rather than stopped the cascade. Foreign investors, after dumping more than 12 trillion won in equities over the two-session period, ended Wednesday as modest net buyers — 231.2 billion won in net purchases — a tentative signal that some institutional money saw the dislocation as an entry point.

BofA’s take. “The sharp decline reflects the outsized leverage in long positions heading into February 28, 2026, when market sentiment was highly bullish on Korean tech due to the aggressive shortage of memory chips used in AI server production,” BofA strategist Chun Him Cheung told Investing.com. The implication: this was not a fundamental repricing of Korea’s economic future — it was a positioning purge, painful but potentially creating opportunity.

Where rational capital might look. For investors with a six-to-twelve-month horizon, the crash has produced a rare dislocation between price and fundamental value in high-quality names. Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix — despite their catastrophic session — retain structural leadership positions in AI-grade memory chips, a market with no near-term substitute suppliers. Analysts at IM Securities and Renaissance Asset Management both noted that if the conflict resolves within one month, a rebound toward 5,500–5,800 on the KOSPI is plausible. Defensive plays in South Korean energy utilities, domestic-demand retailers, and defence contractors — which have benefited from the same geopolitical tension that crushed the broader market — offer asymmetric positioning.

For retail investors caught in forced liquidations, the message is sobering but familiar: leverage borrowed at the peak of euphoria is the most reliable way to transform a geopolitical shock into a personal financial crisis.

Conclusion: The Price of Being the World’s Hottest Market

There is a painful irony at the heart of what happened to South Korea’s stock market this week. The KOSPI was, by virtually every measure, the world’s best-performing major equity index in early 2026. It rose on the back of genuine structural tailwinds — AI memory demand, corporate governance reforms, a re-rating of Korea’s innovation economy by global fund managers. The 40-percent rally in two months was not pure speculation; it was grounded in earnings.

But markets running that fast accumulate fragility. Leverage builds. Concentration intensifies. The margin for error narrows. When an external shock arrives — not a Korean shock, not a chip-sector shock, but a missile fired in the Persian Gulf — there is no buffer. The circuit breakers fired at 9:17 a.m. and could not stop what came afterward.

The KOSPI’s record-breaking crash is not, in isolation, a verdict on South Korea’s economic future. The structural case for its semiconductor giants remains intact. The reforms that re-rated the market over the past year have not been reversed. What has changed is the risk premium: an economy that earns its export surplus in silicon must pay for its energy in oil, and oil now carries a war premium that markets cannot price with confidence.

The Strait of Hormuz is 39 kilometres wide at its narrowest point. For South Korea, that passage has never felt smaller.

FAQs (FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS)

Q1: Why did South Korea’s stock market fall more than any other country’s during the US-Iran war? South Korea’s extreme vulnerability stems from three intersecting factors: it imports approximately 98 percent of its fossil fuels, with around 70 percent sourced from the Middle East via the Strait of Hormuz; its benchmark KOSPI index is heavily concentrated in semiconductor stocks (Samsung and SK Hynix account for close to half the index’s market cap) that had rallied more than 40 percent in early 2026 on margin debt; and a public holiday on Monday March 2 compressed two days of global selling into a single catastrophic Tuesday session.

Q2: How does the March 4, 2026 KOSPI crash compare to the September 11, 2001 drop? The KOSPI fell 12.06 percent on March 4, 2026, narrowly eclipsing the 12.02 percent decline recorded on September 12, 2001, the day after the 9/11 attacks. The intraday low of 12.65 percent was the deepest since April 17, 2000. It is now the worst single-day session in the KOSPI’s 43-year recorded history, surpassing four prior instances of 10-percent-plus declines including those during the dot-com bubble, 9/11, and the 2008 global financial crisis.

Q3: What happened to the Korean won during the KOSPI crash? The Korean won fell sharply during the two-day rout, briefly breaching 1,500 per dollar on Wednesday March 4 — a level not seen since March 2009 at the depth of the global financial crisis — before closing around 1,466 per dollar. The Bank of Korea vowed to respond to “herd-like behaviour” in currency markets and signalled readiness for intervention if volatility persisted.

Q4: Will South Korea’s stock market recover from the US-Iran war selloff? The outlook depends heavily on the duration of the conflict and whether the Strait of Hormuz reopens to normal commercial shipping. Most Seoul-based analysts see two primary scenarios: a quick resolution (within four to five weeks) that triggers a sharp technical rebound toward 5,500–5,800 on the KOSPI, or a prolonged stalemate that sees the index finding a floor near 4,800–5,000 as earnings are revised downward. The structural bull case — driven by AI memory chip demand and corporate governance improvements — has not been invalidated, but the energy-price risk premium has risen substantially.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Insurance

Gulf Insurance Costs Soar 12-Fold Despite Trump Guarantee: The Global Energy Crisis No One Saw Coming

War risk premiums for Strait of Hormuz transits have surged from a pre-crisis baseline of roughly 0.08% to as high as 1% of hull value — a near-12-fold explosion in cost that is quietly strangling global energy trade, even as President Trump promises an insurance backstop through the U.S. Development Finance Corporation.

The Quote That Stops a Ship

Imagine you are the operations director of a midsize Greek tanker company. Your very large crude carrier — a VLCC laden with two million barrels of Saudi crude, worth roughly $160 million at today’s prices — is sitting at anchor in the Gulf of Oman. It was bound for Ningbo. Your broker in London calls Tuesday morning. The hull war risk premium to transit the Strait of Hormuz, if you can get one at all, has just hit 1% of the vessel’s insured value — for a single seven-day period. On a ship valued at $120 million, that is $1.2 million. For one voyage. Last month, the same premium was $96,000.

You tell the captain to hold position.

That decision, replicated by hundreds of operators across the global tanker fleet since the United States and Israel launched joint strikes against Iran on February 28, 2026, is the quiet mechanism behind the most severe disruption to global energy flows since the 1979 Iranian Revolution. It is not missiles or mines that have effectively closed the Strait of Hormuz — it is a spreadsheet, a reinsurer’s risk model, and a 12-fold surge in the price of a specialized insurance policy that most people have never heard of.

The Surge Explained: From 0.08% to Uninsurable

War risk insurance is the unglamorous but indispensable plumbing of global trade. Standard marine policies exclude losses arising from armed conflict; a separate war risk policy fills that gap, and without it, port authorities refuse entry, charterers void contracts, and banks decline to finance cargo. As David Smith, head of marine at insurance broker McGill & Partners, put it bluntly: if you walked into the hull war market right now and said you had a tanker bound through the Strait of Hormuz, there is a genuine possibility you would struggle to find any underwriter prepared to quote terms at all.

The numbers behind the collapse are stark. Before the U.S.-Israeli air campaign against Iran began — what American planners have codenamed “Operation Epic Fury” — war risk premiums for Persian Gulf transits sat at roughly 0.08% to 0.1% of a vessel’s insured hull value on a standard seven-day basis, a baseline consistent with the relatively stable threat environment that followed the 2025 Houthi ceasefire. By March 3, 2026, premiums had surged to as much as 1% of vessel value, even for ships not planning to breach the Strait itself — and underwriters were in some cases declining to quote at all. For a VLCC valued at $120 million, that translates into a single-voyage war risk bill of $1.2 million, versus roughly $96,000 three weeks ago.

The structural driver of this repricing is reinsurance. London’s wholesale marine market does not carry that exposure on its own books — it cedes most of the risk upward to a small group of global reinsurers. When those reinsurers withdrew their support for Gulf war risk extensions in the 72 hours following the February 28 strikes, the primary market followed instantly. The Joint War Committee of Lloyd’s Market Association moved swiftly to expand its list of designated high-risk areas to include Bahrain, Djibouti, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar — a designation that automatically triggers reset clauses in thousands of charter party agreements and financing contracts worldwide.

The Insurer Exodus: A 72-Hour Cancellation Wave

The mechanics of what happened over March 1 and 2 deserve examination, because they reveal a structural vulnerability that no political guarantee — however loudly announced — can easily override.

All 12 members of the International Group of P&I Clubs, the mutual insurance cooperatives that together cover liability risks for approximately 90% of the world’s ocean-going merchant fleet, simultaneously issued 72-hour notices of cancellation for war risk extensions attached to their Gulf policies. Among the prominent names announcing cancellations effective March 5: Gard, Skuld, NorthStandard, the London P&I Club, and the American Club. Japan’s MS&AD Insurance Group separately suspended new underwriting across a broader range of war risk policies covering waters near Iran, Israel, and neighboring countries.

Skuld stated it was working on a buy-back option to reinstate cover at higher premiums. But the key phrase is “higher premiums” — the market was not withdrawing because the risk was uninsurable in principle. It was withdrawing because reinsurers needed to reset pricing to a level that reflected a genuine war environment, not a residual geopolitical tension premium. The parallel to 2022 is instructive: after Russia invaded Ukraine, insurers cancelled Black Sea war risk extensions before new cover was eventually negotiated — at vastly higher cost — as grain exports resumed months later under new terms. The Hormuz situation is structurally similar, but geographically more consequential.

What distinguishes this moment from previous Gulf shipping crises is the breadth of the insurer pullback. During the 1987–1988 Tanker Wars, the market stayed open — pricing adjusted but never fully closed. Today, the combination of advanced Iranian drone technology, demonstrated willingness to target vessels from multiple flags, and an IRGC commander’s declaration that the Strait is “closed” and any vessel attempting passage would be set ablaze has created what Munro Anderson of Vessel Protect, a war insurance specialist within Pen Underwriting, described as a “de facto closure of the strait based primarily on perception of threat rather than tangible blockade.” Perception, in insurance markets, is reality.