Opinion

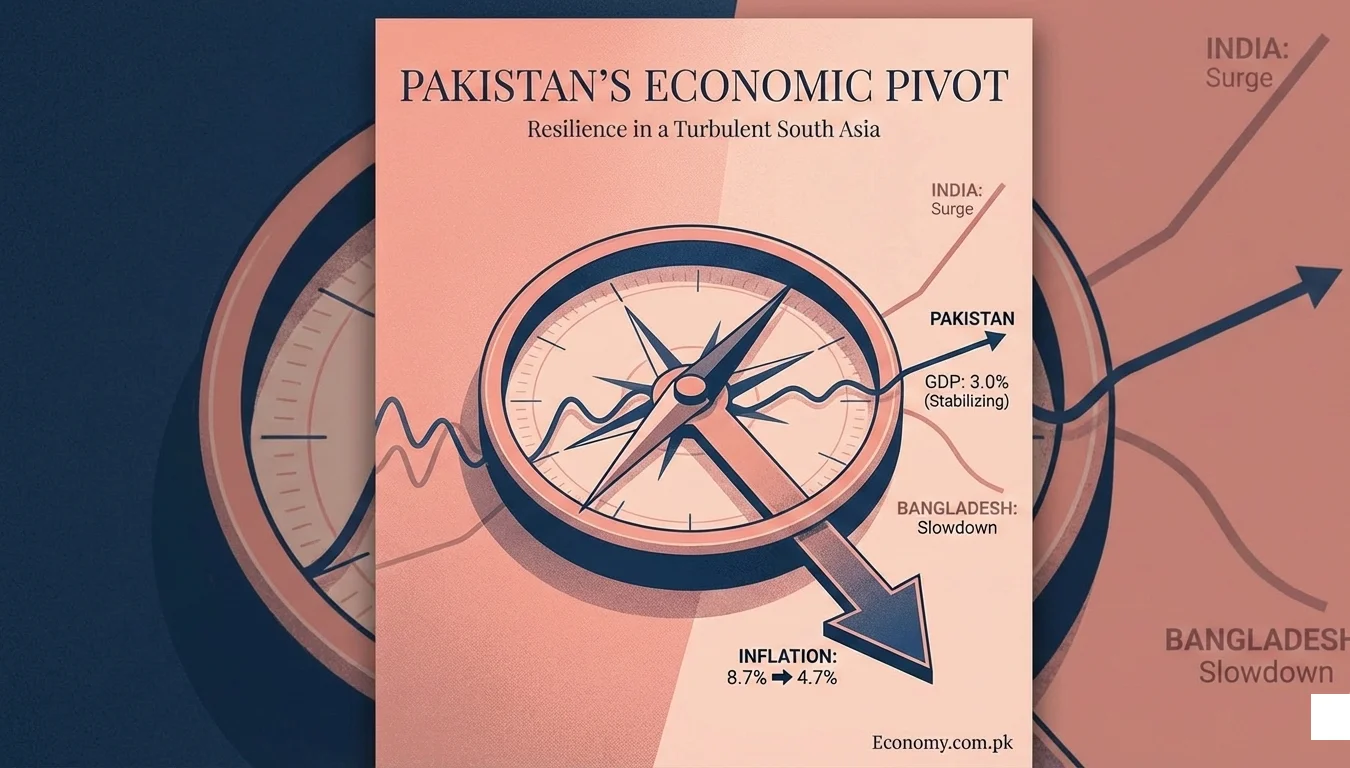

Pakistan’s Economic Pivot: Finding Resilience in a Turbulent South Asia

The narrative surrounding South Asia’s economy has long been dominated by singular giants, but the tides are shifting. For years, the headlines have focused solely on high-speed growth or deepening crises. However, the latest data released by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in its December 2025 Asian Development Outlook (ADO) paints a far more nuanced picture—one of divergence, realignment, and for Pakistan, a critical moment of stabilization.

While the region as a whole is projected to grow at a robust 6.5% in 2025, the internal dynamics are changing. As India continues its consumption-led surge and Bangladesh faces unexpected headwinds, Pakistan is quietly executing a pivot. The numbers suggest that despite political noise and the lingering scars of climate disasters, the Pakistani economy is showing signs of genuine resilience, offering a unique, albeit cautious, investment case for the fiscal year 2025-26.

The Pakistani Pivot: What the Numbers Really Mean

For investors and policymakers fatigued by volatility, the ADB’s latest upgrade is a breath of fresh air. The bank has revised Pakistan’s GDP growth forecast for FY2025 up to 3.0%, a significant improvement from the earlier estimate of 2.7%. This trajectory is expected to hold steady, with a sustained 3.0% forecast for FY2026.

At first glance, 3% might not seem like a headline-grabbing figure compared to historical highs. However, in the context of stabilization, it is monumental. It represents a floor—a foundational level of activity that proves the economy has absorbed the worst of the shocks.

Resilience in Action

The most telling data point, arguably, is not the annual forecast but the quarterly performance. Despite severe flood disruptions that threatened to derail agricultural output, Pakistan’s economy clocked a surprising 5.7% growth in Q4 FY2025. This figure is a testament to the adaptability of Pakistan’s private sector and the hard-won resilience of its agricultural base.

The Inflation Relief

Perhaps the most critical indicator for the common man and the business community is the dramatic cooling of prices. The ADB report highlights a sharp decline in inflation, averaging 4.7% in the first four months of FY2026 (July–October). This is a massive reprieve compared to the suffocating 8.7% recorded during the same period last year.

For the Pakistan Economic Outlook 2025, this drop in inflation is the game-changer. It signals that monetary tightening has worked, supply chains are normalizing, and the central bank may soon have the room to pivot toward pro-growth policies, potentially lowering borrowing costs for the private sector.

The Regional Race: A Comparative Analysis

To understand Pakistan’s position, we must look at the neighborhood. The South Asia Economic Trends revealed in the ADO report show three distinct economic stories unfolding simultaneously.

India: The Consumption Engine

India remains the regional outlier in terms of sheer velocity. The ADB has upgraded India’s growth forecast to 7.2% for 2025, driven largely by robust domestic consumption. India is currently in an expansion phase, leveraging its massive internal market to buffer against global slowdowns. For Pakistan, India serves as a benchmark for what is possible when political stability meets consistent policy frameworks.

Bangladesh: The Unexpected Slowdown

The sharper contrast, however, lies to the east. Bangladesh, often touted as the “miracle” economy, is facing significant friction. The ADB has cut Bangladesh’s growth forecast to 4.7% (down from 5.1%). This deceleration is attributed to export weakness—particularly in the readymade garment sector—and rising political uncertainty.

“Stabilization is not the destination; it is merely the platform. A 3% growth rate keeps the lights on, but it does not employ the millions of youth entering the workforce.“

Pakistan vs India Economy comparisons are common, but the comparison with Bangladesh is currently more relevant. As Bangladesh struggles with export dips and structural adjustments, Pakistan has an opportunity to regain lost ground. The narrative that Pakistan is the “sick man” of South Asia is being challenged by data that shows Pakistan stabilizing while competitors stumble.

Opinion: Turning Stabilization into Acceleration

As the Lead Editor of Economy.com.pk, I view these numbers with “cautious optimism.” Stabilization is not the destination; it is merely the platform. A 3% growth rate keeps the lights on, but it does not employ the millions of youth entering the workforce annually.

To turn this ADB GDP Forecast for Pakistan into a sustained trajectory of 5-6% growth, three things must happen:

- Capitalize on Regional Weakness: With Bangladesh’s export engine sputtering, Pakistan’s textile and manufacturing sectors must aggressively court international buyers looking to diversify supply chains. The stabilization of the Rupee and lower inflation provide the perfect window for this.

- Climate-Proofing is Economic Policy: The 5.7% growth in Q4 FY2025 occurred despite floods. Imagine the potential if our infrastructure was resilient. Investment in climate-smart agriculture is no longer a “green” luxury; it is a hard economic necessity.

- Political Continuity: The data shows that the economy responds to stability. The current recovery is fragile. Any return to chaotic populism could spook the very investors now taking a second look at Pakistani assets.

Conclusion

The data from the Asian Development Bank confirms what analysts on the ground have suspected: the storm is passing. While India sprints and Bangladesh catches its breath, Pakistan is standing firm.

With GDP growth revised upward to 3.0%, inflation nearly halved to 4.7%, and a private sector showing remarkable grit in Q4, the indicators for FY2026 are flashing green. The road ahead requires discipline, but for the first time in years, the economic map of South Asia shows Pakistan not as a crisis point, but as a recovering contender.

**

Disclaimer: This analysis is based on the latest Asian Development Outlook (ADO) data. Investors are advised to conduct their own due diligence.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply

Analysis

Trump Nominates Kevin Warsh as Next Fed Chair: A Conventional Choice with Unconventional Implications

President Donald Trump announced Friday morning that he is nominating Kevin Warsh to succeed Jerome Powell as Federal Reserve Chair CNBC, bringing to a close a five-month search process that has been as much political theater as personnel decision. The choice represents a superficially conventional selection—Warsh is a former Fed governor with crisis-era credentials—yet it arrives at one of the most fraught moments in the central bank’s modern history, raising fundamental questions about monetary policy independence, interest rate trajectory, and the future of American economic governance.

“I have known Kevin for a long period of time, and have no doubt that he will go down as one of the GREAT Fed Chairmen, maybe the best,” CNBC Trump wrote on Truth Social. “On top of everything else, he is ‘central casting,’ and he will never let you down.” CNBC

The nomination of the 55-year-old economist, Wall Street veteran, and Stanford scholar marks a homecoming of sorts for someone who nearly secured the role eight years ago. Yet Warsh returns to a Federal Reserve under siege—facing a Justice Department criminal investigation of Powell, a Supreme Court case testing presidential power over Fed governors, and relentless political pressure from a president who has made aggressive rate cuts a centerpiece of his economic agenda.

Who Is Kevin Warsh?

Warsh’s biography reads like a textbook case study in American financial elite formation. Born in Albany, New York, in 1970, he earned his undergraduate degree in public policy from Stanford University and a law degree from Harvard before joining Morgan Stanley’s mergers and acquisitions department in 1995, where he rose to executive director.

His transition to public service came in 2002 when President George W. Bush appointed him Special Assistant for Economic Policy and Executive Secretary of the National Economic Council. Four years later, at just 35, Bush nominated him to the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, making him the youngest person ever to hold that position—a distinction that remains today.

Warsh’s tenure coincided with the eruption of the 2008 financial crisis, where he served as Chairman Ben Bernanke’s primary liaison to Wall Street Wikipedia and played a pivotal role in crisis management. Bernanke later wrote that Warsh, “with his many Wall Street and political contacts and his knowledge of practical finance,” was among his “most frequent companions on the endless conference calls through which we shaped our crisis-fighting strategy.” Wikipedia

During the September 2008 chaos, Warsh helped engineer the conversion of his former employer Morgan Stanley into a bank holding company, effectively saving the firm from collapse. His Wall Street pedigree and Republican credentials made him invaluable during a crisis that required swift, unconventional action.

Yet Warsh’s Fed tenure ended in controversy. By 2011, he had become increasingly concerned that quantitative easing would lead to inflation Britannica and publicly broke with Bernanke over the second round of bond purchases (QE2). His resignation that March, seven years before his term was set to expire, signaled a fundamental disagreement over the central bank’s post-crisis direction.

Since leaving the Fed, Warsh has served as a Distinguished Visiting Fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, worked with billionaire investor Stanley Druckenmiller at Duquesne Family Office, and sat on the board of directors for UPS. He also conducted an influential independent review of the Bank of England’s monetary policy framework, whose recommendations were adopted by Parliament.

The Nomination Process: A Reality-Show Search

Trump’s search for Powell’s successor has been anything but conventional. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent led a process that at one point considered eleven candidates spanning from former and current Fed officials to prominent economists and Wall Street pros CNBC. The field was eventually narrowed to four finalists: Warsh, current Fed Governor Christopher Waller, BlackRock fixed income executive Rick Rieder, and National Economic Council Director Kevin Hassett.

For months, Hassett appeared to be the front-runner—a veteran Republican economist with strong White House visibility. But Trump’s frequent media appearances praising “the two Kevins” kept Warsh in contention, and the president ultimately decided he couldn’t afford to lose Hassett from his current role. “A lot of people think that this is somebody that could have been there a few years ago,” Euronews Trump told reporters Thursday evening, fueling speculation that had already reached fever pitch.

Bloomberg reported Thursday night that Warsh had visited the White House, sending prediction markets into overdrive. By Friday morning, betting platforms showed Warsh’s odds exceeding 85%.

Market Reaction: Hawkish Credentials Meet Dovish Expectations

Financial markets responded to Warsh’s likely nomination with a complex mixture of relief and apprehension. Stocks fell with US Treasuries as the administration prepared the announcement, a choice viewed as more hawkish than other contenders. Gold slid 2.8% and the dollar gained Bloomberg on Thursday evening as speculation mounted.

The market’s ambivalence reflects Warsh’s inherent contradictions. His historical reputation is that of an inflation hawk who consistently warned of price pressures that never materialized during his 2006-2011 tenure. In September 2009, with unemployment at 9.5% and climbing, Warsh argued that the Fed should begin pulling back on its recovery efforts Wikipedia, warning of an “excessive surge in lending” that could fuel inflation. That inflation never appeared, leading critics like University of Oregon Professor Tim Duy to suggest Warsh prioritized Wall Street over Main Street.

Yet Warsh’s recent rhetoric has shifted markedly. In a Wall Street Journal op-ed last year, he argued that the Fed should “discard its forecast of stagflation” Yahoo! and acknowledged that artificial intelligence would be a “significant” disinflationary force boosting productivity. He has publicly supported lower interest rates—precisely what Trump demands.

This hawkish-to-dovish evolution has left analysts divided. “If the nominee is indeed Warsh, we could actually end up with a Fed that tilts hawkish at the margin,” MarketScreener said Sonu Varghese, global macro strategist at Carson Group. Yet Trump himself has insisted, “He thinks you have to lower interest rates” Yahoo!—his key litmus test for the role.

Commonwealth Bank strategist Kristina Clifton noted the dollar’s rise reflected expectations that Warsh “is a little bit less dovish than perhaps Kevin Hassett” and would “perhaps preserve a little bit more of the Fed’s independence than some of the other candidates would.” MarketScreener

The Independence Question: A Central Bank Under Siege

Warsh’s nomination arrives at a moment of unprecedented political pressure on the Federal Reserve. The Justice Department’s criminal investigation of Powell over testimony regarding the Fed’s $2.5 billion headquarters renovation—the first such probe of a sitting Fed chair—has shocked senators from both parties and raised alarms about central bank independence.

Powell argued the investigation was part of an attempt to intimidate the Fed for its interest rate decisions, undermining its independence. Euronews The probe has created a toxic confirmation environment, with Republican Senator Thom Tillis of North Carolina vowing to block any Fed nominee until the investigation is resolved. “I will oppose the confirmation of any nominee for the Fed—including the upcoming Fed Chair vacancy—until this legal matter is fully resolved,” CNBC Tillis declared.

Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski has joined Tillis in opposition, potentially creating a mathematical problem for Warsh’s confirmation. With 53 Republicans in the Senate but at least two defections, passage is no longer assured—particularly given likely united Democratic opposition, intensified by Trump’s attempt to fire Fed Governor Lisa Cook.

Warsh himself has sent mixed signals on independence. In an April 2025 speech to the Group of Thirty and International Monetary Fund, he called Fed independence “important and worthy” NPR but argued the central bank had weakened its case by overreaching its mandate. “Our constitutional republic accepts an independent central bank only if it sticks closely to its congressionally-directed duty and successfully performs its tasks,” NPR he stated.

More provocatively, Warsh has accused the Fed under Powell of “using independence as a shield from accountability” and said members should “grow up” and “be tough” in the face of criticism. The Hill Such rhetoric suggests a willingness to challenge institutional norms—precisely what troubles defenders of Fed autonomy.

Monetary Policy Implications: Lower Rates, Smaller Balance Sheet

If confirmed, Warsh would inherit a Federal Reserve navigating treacherous terrain. The central bank has cut its benchmark rate by 1.75 percentage points since September 2024, bringing it to a range of 3.5% to 3.75%. Yet inflation remains a good deal from the Fed’s 2% target CNBC, while the labor market has cooled into what economists describe as a “no-fire, no-hire” equilibrium.

Trump wants rates far lower—he has called for rates as low as 1%, compared to the current 3.6% range. Markets, however, expect caution. Traders are pricing in at most two more cuts this year before the benchmark fed funds rate lands around 3% CNBC, which policymakers view as the long-run neutral rate.

Warsh’s distinctive policy combination—lower rates paired with aggressive balance sheet reduction—sets him apart from conventional dovishness. He believes AI-driven productivity gains are disinflationary, justifying aggressive rate cuts, while arguing the Fed’s balance sheet has subsidized Wall Street and should shrink significantly. Yahoo Finance

This approach could reshape the liquidity environment that has supported risk assets since 2008. The Fed’s balance sheet currently stands at roughly $6.5 trillion, down from $8.9 trillion in 2022. Warsh’s anti-quantitative easing stance suggests further reductions ahead, potentially pressuring equity valuations and cryptocurrencies that have historically risen alongside Fed balance sheet expansion.

Australian strategist Damien Boey captured market uncertainty: “The trade-off that he makes with lower rates is that he wants the Fed to have a smaller balance sheet. The markets are reacting as if thinking: ‘What would the world look like with a smaller Fed balance sheet?'” MarketScreener

Historical Context: Echoes of Volcker, Bernanke, and Powell

Warsh’s nomination invites comparison to previous Fed leadership transitions. Like Paul Volcker before Ronald Reagan appointed Alan Greenspan, Powell faces replacement by a president demanding different priorities. Yet unlike Volcker, who left voluntarily after taming inflation, Powell is being ousted while price pressures remain elevated and his term as governor extends until early 2028.

Powell could follow the unconventional path of staying on as a regular governor—a move that would allow him to serve as what some describe as “a bulwark against Trump’s efforts to compromise Fed independence.” CNBC Most Fed chairs have resigned their board positions upon losing the chairmanship, but Powell’s potential decision to remain would reflect the extraordinary circumstances of Trump’s pressure campaign.

Warsh’s relationship with his own mentor, Ben Bernanke, offers instructive precedent. Despite working closely during the crisis, Warsh ultimately broke with Bernanke over QE2, suggesting an independent streak. Yet his recent alignment with Trump’s preferences raises questions about whether he would resist presidential pressure more effectively than Powell has.

JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon—rarely effusive about Fed nominees—reportedly said at a private December conference that Warsh would make “a great chair,” a rare endorsement carrying significant weight in financial circles.

Global Ramifications and the Dollar’s Future

Warsh’s potential Fed leadership extends beyond domestic implications. As a former Fed representative to the G-20 and emissary to Asian economies, he brings international credentials that could prove valuable as Trump pursues an aggressive tariff agenda.

“A Warsh appointment would not only play to the view that Fed independence will be protected, it would also play to the view that whilst some reforms should be expected, it’s not going to really dramatically change the Fed,” MarketScreener noted a strategist at Oversea-Chinese Banking Corp.

The dollar’s initial strength following Warsh speculation reflected confidence in his hawkish pedigree. Yet sustained dollar performance will depend on whether Warsh delivers the aggressive rate cuts Trump demands or maintains the data-dependent approach that has characterized modern Fed policy.

The Path Forward: Confirmation, Implementation, and Consequences

Warsh’s confirmation hearing will likely prove contentious. Senators will probe his evolution from inflation hawk to rate-cut advocate, question his ties to Trump through his father-in-law Ronald Lauder (a major Republican donor), and press him on Fed independence. The Tillis blockade adds procedural complexity, potentially delaying confirmation until the Powell investigation concludes—if it ever does.

Should Warsh clear the Senate, he would face immediate challenges. The Federal Open Market Committee consists of 12 members—seven governors and five rotating regional Fed bank presidents. Building consensus for Trump’s preferred policies among career central bankers skeptical of political interference will test Warsh’s leadership and diplomatic skills.

Moreover, Powell’s potential decision to remain as a governor would create an unusual dynamic: a displaced chair serving alongside his successor, potentially marshaling opposition to policies he views as imprudent. This scenario has no modern precedent and could produce public disagreements that undermine market confidence.

The broader economic backdrop compounds these challenges. Trump’s tariff policies are widely viewed as inflationary, creating tension between the president’s demand for lower rates and the Fed’s price stability mandate. Warsh’s argument that tariffs represent one-time price level adjustments—a view increasingly echoed by some Fed officials—could provide intellectual cover for rate cuts despite elevated inflation. Yet if price pressures persist, Warsh would face the uncomfortable choice between accommodating presidential preferences and fulfilling his statutory mandate.

Conclusion: Continuity, Disruption, or Something In Between?

Kevin Warsh’s nomination represents a paradox wrapped in conventional credentials. On paper, he is precisely the sort of figure markets should find reassuring: a former Fed governor with crisis management experience, academic standing, and bipartisan relationships. His selection over more unconventional candidates like Hassett or outsiders without central banking experience suggests Trump ultimately opted for establishment continuity.

Yet Warsh’s recent rhetoric, his willingness to challenge institutional norms, and his alignment with Trump’s policy preferences signal potential disruption ahead. The combination of lower rates and aggressive balance sheet reduction could reshape American monetary policy in ways that echo his earlier opposition to quantitative easing—only now with presidential blessing rather than opposition.

The ultimate test will be whether Warsh can reconcile his historical hawkishness with Trump’s dovish demands, maintain the Fed’s credibility amid unprecedented political pressure, and navigate economic conditions that may not cooperate with anyone’s preferred policy path. As Financial Times readers know, central banking is ultimately about expectations management—and Warsh inherits an institution whose independence, credibility, and policy framework are all under question.

Markets appear to be pricing in cautious optimism: a Chair who understands financial stability, respects institutional process, yet remains sympathetic to growth-oriented policies. Whether that optimism proves justified may depend less on Warsh’s intentions than on economic realities, political pressures, and the still-unresolved question of what Fed independence means in the Trump era.

The coming months will reveal whether this conventional choice produces unconventional outcomes—or whether the guardrails of institutional process, market discipline, and economic constraints ultimately force convergence toward the cautious, data-dependent approach that has characterized modern central banking. For investors, policymakers, and citizens alike, Warsh’s tenure—should he be confirmed—will offer a defining test of American economic governance at a moment when both inflation and political pressure remain uncomfortably elevated.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

AI

The Voice of the Next Billion: How Uplift AI is Rewiring the Global South’s Digital Frontier

KARACHI — In the sun-drenched cotton fields of southern Punjab, a farmer named Bashir holds a cheap Android smartphone. He doesn’t type; he doesn’t know how. Instead, he presses a button and asks a question in his native Saraiki. Within seconds, a human-sounding voice responds, explaining the exact nitrate concentration needed for his soil based on the morning’s weather report.

This isn’t a speculative vision of 2030. It is the immediate reality being built by Uplift AI, a Pakistani voice-AI infrastructure startup that recently announced a $3.5 million seed round in January 2026. Led by Y Combinator and Indus Valley Capital, the round marks a pivotal shift in the global AI narrative—one where the “next billion users” are brought online not through text, but through the primal, intuitive medium of speech.

A High-Stakes Bet on Linguistic Sovereignty

The funding arrives as Pakistan’s tech ecosystem stages a gritty comeback. Following a 2025 rebound that saw startups raise over $74 million—a 121% increase from the previous year’s doldrums—Uplift AI’s seed round represents one of the largest early-stage injections into pure-play AI in the region.

Joining the cap table is an elite syndicate including Pioneer Fund, Conjunction, Moment Ventures, and a group of high-profile Silicon Valley angels. Their conviction lies in a sobering statistic: 42% of Pakistani adults are illiterate. For them, the LLM revolution of 2023–2024 was a spectator sport. By building foundational voice models for Urdu, Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, Balochi, and Saraiki, Uplift AI is effectively building the “operating system” for a population previously locked out of the digital economy.

The Engineers Who Left Big Tech for the Indus Valley

Uplift AI’s pedigree is its primary moat. Founders Zaid Qureshi and Hammad Malik are veterans of the front lines of voice technology. Malik spent nearly a decade at Apple and Amazon, contributing to the core logic of Siri and Alexa, while Qureshi served as a senior engineer at AWS Bedrock, designing the very guardrails that govern modern enterprise AI.

“Off-the-shelf models from Silicon Valley treat regional languages as an afterthought—a translation layer slapped onto an English brain,” says Hammad Malik, CEO of Uplift AI. “We built our Orator family of models from the ground up. We don’t just translate; we capture the cadence, the cultural nuance, and the soul of the language.”

This “ground-up” philosophy involved a massive, in-house data operation. The startup has spent the last year recording thousands of hours of native speakers across Pakistan’s provinces to ensure their Speech-to-Text (STT) and Text-to-Speech (TTS) engines could outperform global giants like ElevenLabs or OpenAI in local dialects. According to the company, their models are currently 60 times more cost-effective for regional developers than Western alternatives.

Traction: From Khan Academy to the Corn Fields

The market’s response suggests the founders’ thesis was correct. Uplift AI has already secured high-impact partnerships:

- Khan Academy: Dubbed over 2,500 Urdu educational videos, slashing production costs and making world-class education accessible to millions of non-reading students.

- Syngenta: Deploying voice-first tools for farmers to receive agricultural intelligence in their local dialects.

- Developer Ecosystem: Over 1,000 developers are currently utilizing Uplift’s APIs to build everything from FIR (First Information Report) bots for police stations to health-intake systems for rural clinics.

| Language | Status | Market Reach (Est.) |

| Urdu | Live | 100M+ Speakers |

| Punjabi | Live | 80M+ Speakers |

| Sindhi | Live | 30M+ Speakers |

| Pashto | Beta | 25M+ Speakers |

| Balochi/Saraiki | In-Development | 20M+ Speakers |

Competitive Landscape: The Regional “Voice-First” Race

Uplift AI does not exist in a vacuum. In neighboring India, well-funded players like Sarvam AI and Krutrim are racing to build sovereign “Indic” models. However, Uplift’s focus on voice-first infrastructure rather than just text-based LLMs gives it a unique edge in markets with low literacy and high mobile penetration.

While global giants like AssemblyAI or OpenAI’s Whisper offer multilingual support, they often struggle with “code-switching”—the common practice in Pakistan of mixing Urdu with English or regional slang. Uplift’s models are natively trained to understand this linguistic fluidity, making them the preferred choice for local enterprises.

Macro Implications: AI as a GDP Multiplier

The significance of this round extends beyond a single startup. It signals Pakistan’s emergence as a serious contender in the “Sovereign AI” movement. By investing in local infrastructure, the country is reducing its “intelligence trade deficit”—the reliance on expensive, foreign-hosted models that don’t understand local context.

According to Aatif Awan, Managing Partner at Indus Valley Capital, “Voice is the primary gateway to the digital economy in emerging markets. Uplift AI isn’t just a tech play; it’s a productivity play for the entire nation.”

The startup plans to use the $3.5M to expand its R&D team and begin its foray into the MENA (Middle East and North Africa) region, targeting other underserved languages. As the “Generative AI” hype settles into a phase of practical utility, the real winners will be those who can connect the most sophisticated technology to the most fundamental human need: to be understood.

What’s Next?

The success of Uplift AI suggests that the next phase of the AI revolution won’t happen in the boardrooms of San Francisco, but in the streets of Karachi and the farms of Multan. By giving a digital voice to the 42% who cannot read, Uplift AI is not just building a company—it is unlocking a nation.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

Singapore Tightens Training Subsidies as Economic Pressures Mount

SkillsFuture funding reforms signal a strategic pivot toward industry-led upskilling—but at what cost to smaller providers and self-funded learners?

On a humid afternoon in December, Melissa Tan sat in her Jurong West training center watching enrollment numbers tick downward on her computer screen. After fourteen years running a mid-sized vocational training provider, she had weathered economic downturns, policy shifts, and the digitization of Singapore’s workforce. But the new SkillsFuture funding guidelines announced by SkillsFuture Singapore (SSG) in late January felt different. “We’ve built our reputation on serving individuals who want to pivot careers on their own initiative,” she explained over coffee. “Now we need forty percent of our students to be employer-sponsored. That’s a complete business model transformation.”

Tan’s predicament illustrates the complex trade-offs embedded in Singapore’s latest recalibration of its decade-old SkillsFuture initiative. Effective December 31, 2025, SSG has imposed substantially tighter funding criteria on approximately 9,500 training courses across 500 providers—requirements that privilege employer-driven training over individual initiative, data-validated skills over experimental offerings, and quantifiable outcomes over pedagogical innovation. The reforms arrive at a moment when Singapore’s small, open economy faces mounting pressure from technological disruption, an aging workforce, and intensifying regional competition for talent and capital.

The policy shift represents more than administrative housekeeping. It embodies a fundamental question confronting advanced economies worldwide: How do governments balance the democratization of lifelong learning with the imperative to channel scarce public resources toward demonstrable economic returns?

The Mechanics of Tightening

The new guidelines affect what SSG terms “Tier 2” courses—those developing currently demanded skills for workers’ existing roles or professions. (They explicitly exclude SkillsFuture Series courses focused on emerging skills, or career transition programs like Institute of Higher Learning qualifications.) The changes impose three primary gatekeeping mechanisms:

Course approval: Prospective courses must now demonstrate alignment with either (1) skills appearing on SSG’s newly released Course Approval Skills List, derived from data science analysis of job market trends, or (2) documented evidence of industry demand through endorsement from designated government agencies or professional bodies. This represents a marked departure from the previous approach, which permitted a broader range of training offerings to access public subsidies.

Funding renewal threshold: From December 31, 2025 onward, courses seeking to renew their two-year funding cycle must demonstrate that at least 40 percent of enrollments came from employer-sponsored participants. This metric directly measures whether training aligns with enterprise workforce development priorities rather than individual hobbyist pursuits.

Quality survey compliance: Beginning June 1, 2026, courses must achieve a minimum 75 percent response rate on post-training quality surveys, with ratings above the lower quartile. This mechanism aims to eliminate providers who deliver mediocre experiences while gaming enrollment numbers.

A transitional framework softens the immediate impact. Between December 31, 2025 and June 30, 2027, selected course types—including standalone offerings from institutes of higher learning, courses leading to Workforce Skills Qualification Statements of Attainment, and certain other categories—receive a one-year grace period if they fail the 40 percent employer-sponsorship threshold. But the reprieve is temporary; from July 1, 2027, all Tier 2 courses must meet the full criteria.

The Economic Logic: Aligning Supply with Demand

The rationale behind these reforms emerges clearly when viewed against Singapore’s macroeconomic imperatives and recent labor market data. According to SSG’s 2025 Skills Trends analysis, demand for AI-related competencies has surged across industries, with skills like “Generative AI Principles and Applications” experiencing the fastest growth in job postings data. Simultaneously, green economy skills—sustainability management, carbon footprint assessment—and care economy capabilities have gained prominence as Singapore pursues its Green Plan 2030 and grapples with demographic aging.

Yet training providers, responding to consumer demand rather than labor market signals, have often proliferated courses in saturated or declining sectors. The mismatch represents a classic market failure: individual learners, lacking perfect information about employment prospects, gravitate toward familiar or fashionable topics rather than areas of genuine skills shortage. Training providers, incentivized to maximize enrollment volumes, oblige. Public subsidies then inadvertently subsidize this misalignment.

The 40 percent employer-sponsorship requirement cleverly leverages employers’ superior information about workforce needs. Companies investing real money in their employees’ training create a demand-side filter that SSG believes will naturally favor courses addressing actual productivity gaps. “Employers vote with their wallets,” one SSG official noted at the January 27 Training and Adult Education Conference announcing the changes. “If a course can’t attract employer sponsorship, we need to ask whether it’s truly addressing labor market needs.”

From a public finance perspective, the logic is straightforward. Singapore, despite its fiscal strength, operates under self-imposed constraints: a balanced budget requirement, limited borrowing for current spending, and a cultural aversion to expansive welfare states. SkillsFuture expenditures have grown substantially since the program’s 2015 launch—Singaporeans aged 25 and above have collectively claimed over S$1 billion in SkillsFuture Credits, with enhanced subsidies for mid-career workers (aged 40-plus) adding further fiscal pressure. Ensuring these outlays generate measurable employment and productivity outcomes becomes imperative as the government contemplates longer-term structural challenges: an aging society requiring expanded healthcare spending, investments in digital infrastructure and green transition, and resilience measures against external economic shocks.

Global Context: Singapore’s Experiment in Comparative Relief

To appreciate the boldness of Singapore’s approach, consider its divergence from other advanced economies’ lifelong learning models. Denmark’s flexicurity system combines generous unemployment benefits with extensive active labor market policies, including subsidized adult education. But Denmark can afford this largesse through high taxation (total government revenue exceeds 46 percent of GDP, versus Singapore’s 20 percent) and a homogeneous, highly unionized workforce. South Korea’s K-Digital Training initiative, launched in 2020, channels subsidies toward digital skills bootcamps—but targets primarily youth and unemployed workers, not the broader workforce Singapore aims to reach.

France’s Compte Personnel de Formation (CPF) offers perhaps the closest parallel: a portable training account funded through payroll levies, giving workers autonomy over skill development. Yet France’s system has faced criticism for fraud, low-quality providers gaming the system, and inadequate alignment with labor market needs—precisely the pathologies Singapore’s reforms seek to preempt. A 2021 report in The Economist examining retraining programs across OECD countries found that success correlated strongly with employer involvement and labor market relevance, rather than mere accessibility.

Singapore’s model occupies a distinctive middle ground: universal entitlements (every citizen aged 25-plus receives credits), but channeled through market mechanisms and employer validation. The SkillsFuture reforms effectively tighten the alignment mechanism without abandoning the universalist principle—a pragmatic compromise characteristic of Singapore’s technocratic governance style.

The Squeeze on Training Providers: Winners and Losers

The employer-sponsorship threshold creates clear winners and losers among training providers. Large, established players with existing corporate relationships—polytechnics, ITE, private training centers serving multinational corporations—possess natural advantages. They can leverage long-standing contracts, industry advisory boards, and placement track records to attract employer-sponsored enrollments.

Smaller providers face steeper challenges. Many built their businesses serving self-funded mid-career professionals seeking new skills or side ventures—precisely the demographic segment the reforms indirectly penalize. “We’ve invested heavily in emerging areas like blockchain development and sustainability consulting,” explained one boutique training center director who requested anonymity. “These are forward-looking skills, but companies aren’t yet sponsoring at scale because the roles barely exist in their organizations. Under the new rules, we’re essentially being told to wait until the demand becomes mainstream—by which point the opportunity has passed.”

The enrolment cap mechanism, while intended to prevent gaming, compounds the squeeze. Courses reaching their enrollment limit before the funding renewal check (six months prior to the end of the two-year validity period) must pass quality checks before accepting additional students. High-demand courses thus face bureaucratic friction at the worst possible moment—when they’ve demonstrated market appeal. Lower-demand courses, by contrast, may never hit enrollment thresholds requiring scrutiny, creating a perverse incentive structure.

Training providers serving niche industries face particular vulnerability. Specialized sectors like maritime law, conservation biology, or heritage preservation generate modest enrollment volumes and limited employer-sponsorship rates (small firms in these fields often lack formal training budgets). Yet these represent precisely the differentiated capabilities that sustain Singapore’s position as a diversified, knowledge-intensive economy beyond the big four sectors (finance, logistics, technology, manufacturing).

Access and Equity: The Self-Funded Learner’s Dilemma

The employer-sponsorship emphasis raises important equity questions. Not all workers enjoy employer-sponsored training opportunities equally. Research by Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower shows that company-sponsored training tends to concentrate among degree-holders, professionals, and employees of large firms. Rank-and-file workers in SMEs, gig economy participants, and those in precarious employment—precisely the groups most vulnerable to technological displacement—face significant barriers.

Consider Raj Kumar, a 47-year-old logistics coordinator whose employer, a small freight forwarding company, lacks a formal training budget. Kumar has used SkillsFuture credits to complete courses in data analytics and digital supply chain management, hoping to transition into a more technology-oriented role. Under the new guidelines, his preferred courses may lose funding eligibility if they fail to attract sufficient employer sponsorship—forcing him to either pay full cost or choose less relevant but better-subsidized alternatives.

Women reentering the workforce after caregiving breaks present another equity concern. These mid-career returners often invest in self-funded retraining to compensate for skills atrophy or career pivots. Employer-sponsorship requirements create a catch-22: they need training to become employable, but courses require employer interest to remain subsidized.

SSG officials argue that alternative pathways remain available—SkillsFuture Career Transition Programs explicitly serve career switchers, and mid-career enhanced subsidies (covering up to 90 percent of course fees for Singaporeans aged 40-plus) continue supporting self-funded learning. But the distinction between “career transition” and “skills upgrading” proves blurry in practice. Many mid-career workers pursue incremental skill acquisition that doesn’t constitute wholesale career change yet enables internal mobility or role evolution. The new framework may inadvertently penalize this gray zone of professional development.

Data-Driven Skill Identification: Promise and Pitfalls

The Course Approval Skills List represents one of SSG’s more innovative elements. Using natural language processing and machine learning algorithms, SSG analyzes job posting data, wage trends, and hiring patterns to identify skills experiencing demand growth. The 2025 Skills Trends report reveals that 71 skills—spanning agile software development, sustainability management, and client communication—demonstrated consistently high demand and transferability across 2022-2024, with trends expected to continue into 2025.

This data-driven approach offers significant advantages over traditional expert panels or industry surveys. It’s faster, more comprehensive, and less subject to lobbying by incumbent industry players. The methodology also permits granular analysis—SSG now tracks not just skill categories but specific applications and tools (Python libraries, ERP systems, design software) required in job roles.

However, data-driven skill identification harbors limitations. Job postings reflect current employer preferences, not future needs. Emerging disciplines—quantum computing applications, circular economy frameworks, AI ethics—may barely register in job posting data until they’ve already achieved critical mass. By then, first-mover advantages have vanished. If training providers can only offer courses on SSG’s approved list, Singapore risks systematically underinvesting in forward-looking capabilities.

The methodology also privileges skills easily described in job postings. Tacit knowledge, soft skills, and creative competencies prove harder to quantify through algorithmic analysis. Yet these capabilities—judgment, cross-cultural communication, ethical reasoning—often determine long-term career success and organizational adaptability. A training ecosystem optimized for algorithmically identifiable skills may inadvertently neglect the human qualities most resistant to automation.

The Broader Stakes: Singapore’s Competitiveness Calculus

The SkillsFuture reforms must be understood within Singapore’s broader economic development strategy. The city-state has staked its future on becoming a hub for advanced manufacturing, digital services, sustainability innovation, and high-value professional services—sectors requiring a workforce that continuously upgrades capabilities. With neighboring countries investing heavily in technical education (Vietnam’s IT workforce, Thailand’s Eastern Economic Corridor initiative) and established hubs like Hong Kong and Seoul competing for similar industries, Singapore cannot afford complacency.

Yet the tightening carries risks. If Singapore’s training ecosystem becomes too employer-driven and algorithmically determined, it may sacrifice the experimental, entrepreneurial energy that has historically fueled its adaptive capacity. Many of Singapore’s successful industry pivots—from petrochemicals to biotech, from port logistics to digital banking—emerged from individuals and organizations pursuing capabilities ahead of obvious market demand.

The reforms also reflect broader tensions in Singapore’s governance model. The technocratic state excels at efficiency, optimization, and resource allocation toward measurable objectives. These strengths propelled Singapore from third-world poverty to first-world prosperity in two generations. But efficiency-maximizing systems can become brittle when confronted with uncertainty and ambiguity. Training that produces clear, quantifiable outcomes in stable domains may underperform when facing discontinuous change or nonlinear technological shifts.

Forward-Looking Implications: What Comes Next

The January 2026 announcement likely represents the opening salvo in a longer recalibration of Singapore’s lifelong learning architecture. Several trends warrant attention:

Increased emphasis on outcomes-based funding: Expect SSG to develop more sophisticated metrics beyond employer sponsorship—wage progression, job placement rates, productivity enhancements. The agency has already signaled interest in tracking post-training employment outcomes. Future iterations may adjust subsidy levels based on demonstrated impact.

Evolution of the Skills List methodology: As SSG refines its algorithmic approaches, the Course Approval Skills List will likely become more dynamic—updated quarterly rather than annually, incorporating leading indicators beyond job postings, and potentially using predictive modeling to anticipate emerging needs.

Differentiated treatment by sector: SSG may recognize that employer-sponsorship patterns differ across industries. Creative sectors, startups, and SME-dominated fields may receive adjusted thresholds or alternative validation mechanisms.

Greater integration with immigration and talent policy: The skills identified through SkillsFuture’s data infrastructure will increasingly inform Singapore’s employment pass criteria, tech.pass requirements, and sectoral talent initiatives. Training subsidies and immigration policy will converge into a unified human capital strategy.

Experimentation with training innovation zones: To preserve space for experimental offerings, Singapore may designate sandbox environments where providers can test new course concepts with lighter regulatory oversight before scaling.

The Danish Comparison: Lessons from Flexicurity

It’s instructive to contrast Singapore’s approach with Denmark’s vaunted flexicurity model, often cited as a gold standard for lifelong learning. Denmark spends approximately 2.5 percent of GDP on active labor market policies, including extensive adult education subsidies. Workers displaced by technological change or trade shocks can access generous retraining programs with income support.

But Denmark’s system operates in a fundamentally different institutional context. High trust between labor unions, employers, and government enables coordinated approaches to workforce adjustment. Collective bargaining determines training priorities. Social insurance funds (financed through high payroll taxes) cushion income shocks during reskilling. Cultural norms around equality and solidarity legitimize substantial transfers to support individual skill development.

Singapore lacks these institutional preconditions. Its tripartite labor relations model (government-union-employer cooperation) provides some coordination, but stops short of Nordic-style corporatism. The country’s fiscal conservatism precludes Danish-level spending. And Singapore’s multicultural, immigrant-heavy society (40 percent of the population are foreign workers or residents) complicates solidarity-based social insurance.

The SkillsFuture reforms implicitly recognize these constraints. Rather than expand public spending, they aim to spend existing resources more strategically. Rather than rely on trust-based coordination, they deploy data analytics and market mechanisms. This represents neither a superior nor inferior model, but an adapted solution to Singapore’s particular constraints.

The Economist’s Verdict: Calculated Risk or Overreach?

From a pure economic efficiency standpoint, the reforms possess clear merits. Channeling training subsidies toward employer-validated, data-confirmed skills should improve returns on public investment. The employer-sponsorship threshold creates skin-in-the-game dynamics that filter out marginal or dubious training offerings. And the quality survey requirements introduce accountability mechanisms previously absent.

Yet efficiency gains come with potential costs. By privileging current labor market demand over forward-looking capability building, Singapore may diminish its adaptive capacity. The employer-sponsorship threshold, while logical, risks excluding individuals in precarious employment or career transition phases. And the centralization of skill identification—however data-driven—concentrates epistemic power in a single agency that, like all institutions, harbors blind spots.

The optimal balance remains elusive. Singapore’s technocratic governance has historically navigated such trade-offs adeptly, adjusting policies as evidence accumulates. The transitional provisions built into the reforms suggest policymakers recognize implementation risks. Whether these safeguards prove sufficient will emerge over the next eighteen months as providers, employers, and individual learners respond to the new incentives.

What This Means for Stakeholders

For employers: The reforms create opportunities to influence training supply by directing sponsorship toward strategically valuable skills. Forward-thinking HR departments should inventory critical competencies, identify skill gaps, and proactively engage training providers to develop relevant curricula. SMEs, often lacking structured training budgets, may face disadvantages unless industry associations or government intermediaries help aggregate demand.

For training providers: Survival requires pivoting toward corporate partnerships and employer-sponsored enrollments. This means investing in business development capabilities, building industry advisory boards, and potentially consolidating to achieve scale. Providers serving niche or emerging fields face particularly acute pressures—they must either find creative ways to demonstrate industry demand or accept exit from the subsidized market.

For individual learners: Self-funded skill development becomes costlier and riskier. Prudent strategies include leveraging Career Transition Programs when making significant pivots, prioritizing employer-sponsored opportunities where available, and focusing SkillsFuture credits on courses appearing on SSG’s approved skills list. Mid-career workers should proactively discuss training needs with employers to access sponsorship.

For policymakers elsewhere: Singapore’s experiment offers lessons beyond its borders. The employer-sponsorship threshold provides a demand-side filter without abandoning universal access—a model potentially applicable in other advanced economies facing similar efficiency-equity trade-offs. The data-driven skills identification methodology, while imperfect, represents an improvement over purely expert-driven approaches. And the transitional framework demonstrates how aggressive policy reforms can incorporate adjustment periods to mitigate disruption.

The Bigger Picture: Singapore’s Perpetual Adaptation

Step back from the technical details, and the SkillsFuture reforms embody a deeper pattern: Singapore’s continuous recalibration in response to shifting circumstances. The 2015 SkillsFuture launch represented an initial bet on individual empowerment and lifelong learning. A decade’s experience has revealed implementation challenges—misaligned incentives, quality concerns, sustainability questions. The 2025-26 reforms adjust the model based on this learning.

This adaptive approach—launching initiatives, monitoring outcomes, adjusting parameters—characterizes Singapore’s developmental trajectory. The country pivoted from entrepôt trade to manufacturing to services to knowledge economy not through prescient master plans, but through iterative experimentation and course correction. The SkillsFuture reforms continue this tradition.

Yet adaptation has limits. Each course correction narrows future options. Path dependencies emerge. The shift toward employer-driven training may prove difficult to reverse if individual-initiative learning atrophies. Data-driven skill identification, once institutionalized, creates constituencies defending existing methodologies. Singapore’s policymakers must balance the need for optimization with preserving optionality.

Conclusion: The Test Ahead

The SkillsFuture funding tightening represents a calculated bet: that aligning training subsidies with employer demand and labor market data will enhance returns on human capital investment without unduly compromising access or innovation. It’s a quintessentially Singaporean solution—technocratic, efficiency-oriented, data-driven, yet wrapped in rhetoric of lifelong learning and social mobility.

Whether the bet pays off depends on execution and adaptation. Will the employer-sponsorship threshold effectively filter quality while preserving access for vulnerable workers? Will the Skills List methodology prove sufficiently forward-looking, or will it systematically underweight emerging capabilities? Will training providers adapt successfully, or will the sector consolidate in ways that reduce diversity and experimentation?

The answers will emerge gradually as the reforms take effect. Melissa Tan, the training provider director pondering her center’s future that humid December afternoon, exemplifies the stakes. Her ability to navigate the new landscape—finding corporate partners, aligning offerings with approved skills, maintaining quality—will determine not just her business survival but the aggregate health of Singapore’s training ecosystem.

For a small, open economy in a volatile world, the quality of that ecosystem matters immensely. Singapore’s prosperity rests not on natural resources or scale, but on its people’s capabilities. As artificial intelligence reshapes work, climate imperatives transform industries, and geopolitical tensions fragment global markets, continuous skill upgrading becomes not a policy choice but an existential imperative.

The SkillsFuture reforms, whatever their shortcomings, recognize this reality. They represent not the final word on lifelong learning policy, but another iteration in Singapore’s ongoing experiment in sustaining adaptability at the national scale. The city-state’s track record suggests it will continue adjusting, learning, and recalibrating as conditions evolve.

That flexibility—the institutional capacity to course-correct without abandoning core commitments—may prove Singapore’s most valuable skill of all.

Sources:

- SkillsFuture Singapore Official Announcement, January 27, 2026

- Skills Demand for the Future Economy Report 2025

- TPGateway SSG Funding Guidelines

- The Economist, “Retraining Low-Skilled Workers,” Special Report, January 2017

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

-

Markets & Finance3 weeks ago

Markets & Finance3 weeks agoTop 15 Stocks for Investment in 2026 in PSX: Your Complete Guide to Pakistan’s Best Investment Opportunities

-

Global Economy4 weeks ago

Global Economy4 weeks agoWhat the U.S. Attack on Venezuela Could Mean for Oil and Canadian Crude Exports: The Economic Impact

-

Asia4 weeks ago

Asia4 weeks agoChina’s 50% Domestic Equipment Rule: The Semiconductor Mandate Reshaping Global Tech

-

Investment3 weeks ago

Investment3 weeks agoTop 10 Mutual Fund Managers in Pakistan for Investment in 2026: A Comprehensive Guide for Optimal Returns

-

Global Economy1 month ago

Global Economy1 month agoPakistan’s Export Goldmine: 10 Game-Changing Markets Where Pakistani Businesses Are Winning Big in 2025

-

Global Economy1 month ago

Global Economy1 month ago15 Most Lucrative Sectors for Investment in Pakistan: A 2025 Data-Driven Analysis

-

Global Economy1 month ago

Global Economy1 month agoPakistan’s Economic Outlook 2025: Between Stabilization and the Shadow of Stagnation

-

China Economy4 weeks ago

China Economy4 weeks agoChina’s Property Woes Could Last Until 2030—Despite Beijing’s Best Censorship Efforts

Pingback: Pakistan's Strategic Economic Position in South Asia - The Economy