Geopolitics

How Troubled Is the Iranian Economy?

The shopkeeper in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar no longer bothers checking the official exchange rate. Every morning, he opens his phone to WhatsApp groups where the real price of the dollar flickers like a fever chart—120,000 rials one hour, 135,000 the next, sometimes 150,000 by afternoon. “The number doesn’t matter anymore,” he tells a regular customer, weighing out pistachios with hands that have measured nuts and currency crises for three decades. “What matters is that yesterday’s salary buys half of yesterday’s goods.” Outside, in the labyrinthine alleys where merchants have traded since the Safavid era, the mood is brittle. When the rial plunged past the psychologically devastating threshold of 700,000 to the dollar in late 2025—a figure that would have seemed apocalyptic just years earlier—something fractured in the social contract between Iran’s 88 million citizens and their government.

The protests that erupted were not merely about currency. They were about the accumulated weight of sanctions, mismanagement, and dashed expectations—a generation raised on promises of prosperity now queuing for subsidized bread. The government’s response was swift and brutal: internet blackouts, mass arrests, dozens dead in street clashes. By January 2026, the demonstrations had been largely suppressed, the streets quieted through force. Yet the underlying economic rot that sparked the unrest remains unaddressed, a malignancy spreading through Iran’s financial organs while the world watches a slow-motion collapse of what was once the Middle East’s second-largest economy.

This is not merely an Iranian story. It reverberates through global oil markets, shapes the calculus of nuclear negotiations, and has elevated unlikely opposition figures like Reza Pahlavi—son of the deposed Shah—into positions of potential political relevance for the first time in decades. Understanding how deeply troubled Iran’s economy has become requires looking beyond exchange rates to the structural fractures beneath: the oil dependency that sanctions have weaponized, the subsidy system that simultaneously bankrupts the state and enslaves the public, and the geopolitical isolation that has turned economic policy into a game of survival rather than prosperity. The question is no longer whether Iran faces an economic crisis, but whether that crisis will metastasize into something the Islamic Republic cannot contain.

How Financially Unstable Has Iran Become in 2026?

The Currency Catastrophe and Inflation Spiral

The Iranian rial’s trajectory tells a story of cascading financial collapse. As of January 2026, the currency trades at approximately 700,000–750,000 rials per US dollar on the unofficial market—a staggering depreciation from roughly 32,000 rials per dollar when the Trump administration reimposed comprehensive sanctions in 2018. This represents a loss of over 95% of the currency’s value in less than eight years, an economic evisceration rarely seen outside of hyperinflationary episodes in Zimbabwe or Venezuela.

The official rate, maintained through dwindling foreign exchange reserves and increasingly desperate interventions by the Central Bank of Iran, hovers around 420,000 rials per dollar—a figure that exists primarily on paper and serves mainly to subsidize essential imports and enable corruption through arbitrage. The gap between official and market rates has become a barometer of state dysfunction, widening whenever geopolitical tensions spike or sanctions enforcement tightens.

Inflation has become the daily tax on Iranian life. Official figures from Iran’s Statistical Center put annual inflation at approximately 42% as of late 2025, though independent economists and international observers estimate the real rate for food and essential goods approaches 60-70%. Housing costs in Tehran have surged beyond the reach of middle-class families; a modest apartment now requires years of combined household savings for a down payment. The price of cooking oil, chicken, and eggs—staples of Iranian cuisine—have tripled or quadrupled in the past two years alone.

Key economic indicators for Iran (2026 estimates):

- Inflation rate: 42% official, 60-70% for food and essentials

- GDP growth: -2% to -3% (contraction)

- Unemployment: 11-12% official, youth unemployment approaching 25%

- Currency depreciation: 95%+ since 2018

- Foreign reserves: Estimated $10-20 billion (down from $120+ billion in 2012)

GDP Contraction and the Non-Oil Sector Collapse

Iran’s gross domestic product has been shrinking in real terms for much of the past five years. The International Monetary Fund projects a contraction of 2-3% for the 2025-2026 fiscal year, marking the continuation of a trend that has seen Iran’s economy oscillate between stagnation and recession since maximum pressure sanctions returned. In purchasing power parity terms, GDP per capita has regressed to levels last seen in the early 2000s—an entire generation’s potential prosperity erased.

The non-oil sector, which reformist economists once hoped would diversify Iran away from petroleum dependency, has instead withered under the combined weight of sanctions, currency volatility, and domestic mismanagement. Manufacturing output has declined as companies struggle to import raw materials and machinery parts. The automotive sector, once a source of national pride with production exceeding one million vehicles annually, now operates at roughly 40% capacity. International partnerships with French, German, and Japanese manufacturers evaporated when sanctions snapped back, leaving Iranian carmakers to produce outdated models with smuggled components.

Small and medium enterprises—the backbone of employment in any healthy economy—face existential challenges. Access to credit has evaporated as banks, themselves drowning in non-performing loans estimated at over 40% of total lending, restrict new financing. The rial’s volatility makes business planning impossible; contracts signed in the morning can be rendered unprofitable by afternoon exchange rate movements. Many entrepreneurs have simply given up, closing shop or pivoting to speculative activities like cryptocurrency trading and gold smuggling.

The Oil Dependency Trap and Sanctions Warfare

Despite decades of rhetoric about economic diversification, Iran remains hostage to petroleum exports. Oil and gas revenues constitute an estimated 60-70% of government income and over 80% of export earnings. When sanctions effectively barred Iran from global oil markets in 2018-2020, government revenue collapsed, forcing Tehran into desperate measures: slashing public investment, delaying salary payments to civil servants, and monetizing deficits through Central Bank money printing that fueled inflation.

Though Iran has found creative sanctions-busting methods—selling oil at steep discounts to China through shadowy networks of front companies and ship-to-ship transfers—export volumes remain well below potential. Iran currently exports an estimated 1.2-1.4 million barrels per day, compared to over 2.5 million barrels before sanctions. The discount required to circumvent sanctions—often 15-20% below market prices—means Iran earns far less per barrel than Gulf competitors, hemorrhaging billions in annual revenue.

The non-oil export sector, which might compensate, remains underdeveloped and plagued by sanctions complications. Iran exports pistachios, carpets, petrochemicals, and some manufactured goods to neighboring countries, but payment mechanisms are tortuous. Banking sanctions mean transactions must go through barter arrangements or cryptocurrency channels, adding costs and uncertainty. The tourism industry, which briefly flourished during the 2015-2018 sanctions relief period, has vanished again as international visitors disappeared.

Unemployment, Poverty, and Social Fracture

Official unemployment stands at 11-12%, but these figures drastically understate reality. Youth unemployment—the demographic time bomb that terrifies the regime—approaches 25% and reaches even higher levels among university graduates. Iran produces hundreds of thousands of engineering, science, and humanities graduates annually, but the sanctioned, stagnating economy cannot absorb them. The result is a catastrophic brain drain: skilled Iranians emigrate to Turkey, the UAE, Europe, and North America in numbers unseen since the immediate post-revolution exodus.

Poverty has metastasized. While the Iranian government does not publish comprehensive poverty statistics, independent research suggests that approximately 30-35% of the population now lives below the poverty line, defined as lacking the income to afford basic nutrition and housing. This represents a doubling of poverty rates since 2018. The middle class, once the bedrock of Iranian society, has been hollowed out—professionals and civil servants with fixed salaries watch their purchasing power evaporate monthly.

The government’s response—expanding cash handouts and subsidies—has created fiscal unsustainability while failing to address root causes. Universal basic income transfers reach most Iranian households, but at levels rendered increasingly meaningless by inflation. Subsidized goods are available but require hours of queuing and connection to distribution networks controlled by the Revolutionary Guards and affiliated foundations. This has created a peculiar economy of dependence: citizens hate the system that impoverishes them yet cannot survive without its handouts.

What Circumstances Have Elevated Reza Pahlavi to Prominence?

The resurgence of Reza Pahlavi—eldest son of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the Shah deposed in 1979—into political relevance would have seemed fantastical a decade ago. For years, the crown prince lived in quiet exile in Maryland, a historical curiosity maintaining ceremonial ties to a dwindling community of Iranian royalists. Yet the economic desperation and suppressed fury of 2022-2023 protests, followed by the 2025 economic collapse, created space for opposition figures once dismissed as irrelevant.

The Vacuum of Opposition Leadership

Iran’s opposition landscape has long been fragmented and ineffective. Reformist politicians who operate within the Islamic Republic’s framework—figures like former presidents Mohammad Khatami and Hassan Rouhani—are constrained by red lines they cannot cross. Diaspora opposition groups are balkanized, divided by ideology, ethnicity, and personalities. Meanwhile, the regime has systematically destroyed independent political organizations through imprisonment, exile, and intimidation.

Into this vacuum stepped Pahlavi, who has carefully cultivated a modern, democratic image. He advocates for a constitutional referendum, secular governance, and national reconciliation—positions designed to appeal to diverse constituencies without explicitly demanding monarchy’s restoration. His social media presence, managed with professional savvy, reaches millions of young Iranians who have no memory of his father’s authoritarian rule but see in him an alternative to the Islamic Republic’s theocracy.

The 2022 protests following Mahsa Amini’s death were a turning point. As thousands chanted “Woman, Life, Freedom” and openly called for regime overthrow, Pahlavi positioned himself as a unifying voice for change. He condemned violence, called for international support, and articulated a vision of democratic Iran—carefully calibrated messaging that garnered unprecedented attention. Western media outlets began covering him seriously for the first time in decades, and polling among diaspora Iranians showed rising favorability.

The Symbolism of Pre-Revolutionary Nostalgia

Economic misery has bred selective amnesia about Iran’s pre-revolutionary past. Older Iranians remember the Shah’s era as one of relative prosperity, modernization, and global respect—conveniently forgetting the SAVAK secret police, corruption, and inequality that fueled the 1979 revolution. Younger Iranians, educated but underemployed, compare their constrained present not to the 1970s reality but to an idealized vision of what might have been had revolution never occurred.

Pahlavi skillfully leverages this nostalgia while distancing himself from his father’s authoritarianism. He speaks of democracy, human rights, and economic freedom—concepts that resonate with a population exhausted by theocratic micromanagement of daily life. The Pahlavi name, once toxic, has been partially rehabilitated through the Islamic Republic’s own failures. When the regime can neither deliver prosperity nor tolerate dissent, alternative visions gain currency.

International Attention and Legitimacy

Western governments and media, searching for Iranian opposition interlocutors, have granted Pahlavi platforms once unimaginable. He has addressed policy forums, given interviews to major publications, and met with legislators in Washington and European capitals. This international visibility creates a feedback loop: attention abroad boosts credibility at home, particularly among Iranians who consume foreign media through VPNs.

Whether Pahlavi represents genuine political potential or merely symbolic opposition remains debatable. Inside Iran, his support is difficult to measure given repression and the impossibility of free polling. Some see him as a transitional figure who could facilitate regime change without being its ultimate beneficiary. Others dismiss him as a Western creation with no organic constituency. What’s undeniable is that economic collapse has made the previously unthinkable—regime change involving monarchist symbols—at least discussable.

What Is at Stake in Potential Iranian Regime Change?

Economic Stakes: Reconstruction vs. Continued Decline

A regime change scenario presents both enormous opportunity and catastrophic risk for Iran’s economy. On one hand, a post-Islamic Republic government could potentially unlock sanctions relief, reintegrate into global financial systems, and attract the investment desperately needed to rebuild infrastructure and industry. Iran possesses substantial human capital—an educated population of 88 million—and vast natural resources beyond oil: minerals, agricultural potential, and strategic geographic position connecting Europe, Asia, and the Middle East.

Foreign direct investment, which currently trickles in at under $2 billion annually, could surge if sanctions lift and political risk declines. Iranian oil production could rapidly expand to 4+ million barrels daily, generating tens of billions in annual revenue. The return of Iranian banks to the SWIFT system would normalize trade. The tourism industry could flourish given Iran’s extraordinary cultural heritage.

Yet the path from collapse to reconstruction is treacherous. Regime change rarely unfolds smoothly, particularly in countries with Iran’s regional entanglements and internal complexities. Economic transitions following regime change have mixed records: consider Libya’s descent into chaos after Gaddafi, versus South Africa’s managed transition from apartheid. Iran’s centralized state structure, Revolutionary Guards’ economic dominance, and sanctions-spawned black market networks could prove difficult to dismantle without triggering chaos.

The immediate post-transition period would likely see economic turbulence: capital flight, currency instability, and political uncertainty deterring investment. The Revolutionary Guards control an estimated 40% of the economy through front companies and foundations—unwinding this would require either accommodation or confrontation. Subsidy reform, necessary for fiscal sustainability, would spark immediate popular backlash as prices surge. International creditors would demand debt restructuring.

Geopolitical Stakes: Regional Realignment and Nuclear Questions

Iran’s potential regime change would reshape Middle Eastern geopolitics more profoundly than any event since the 1979 revolution itself. The Islamic Republic has built an axis of influence spanning Lebanon (Hezbollah), Syria (Assad regime), Iraq (Shia militias), and Yemen (Houthis). A new Iranian government—particularly one aligned with Western interests—could withdraw support from these proxies, fundamentally altering regional power dynamics.

Israel and Saudi Arabia, Iran’s primary adversaries, view regime change as potentially beneficial but also unpredictable. An unstable, fragmenting Iran could be more dangerous than a repressive but coherent Islamic Republic. The nuclear program remains the ultimate wildcard: would a new government abandon enrichment in exchange for sanctions relief, or maintain it as a nationalist symbol? The fate of Iran’s uranium stockpiles and centrifuge infrastructure would be central to any transition negotiation.

Russia and China, Iran’s quasi-allies of convenience, would lose a strategic partner useful primarily for its opposition to American influence. Their investments in Iranian infrastructure and energy could become political liabilities in a pro-Western Iran. Conversely, Europe and the United States would gain opportunities to reintegrate Iran into Western-led international institutions, potentially stabilizing oil markets and reducing Middle Eastern tensions.

Social Stakes: Sectarian Tensions and National Identity

Regime change would force Iran to confront suppressed questions of identity, religion, and governance that the Islamic Republic settled through authoritarian imposition. Would a post-theocratic Iran remain an Islamic country, just with secular governance? How would the Shia clerical establishment, deeply embedded in society, adapt to reduced political power? What role would ethnic minorities—Azeris, Kurds, Arabs, Baloch—demand in a new constitutional order?

The risk of Yugoslavia-style fragmentation seems low given Iran’s strong historical national identity predating the Islamic Republic. Yet ethnic tensions exist, particularly in border regions where Kurdish and Baloch insurgencies simmer. A weak central government emerging from regime change could face separatist challenges.

Women’s rights would be central to any transition, given their leadership in recent protests. The compulsory hijab, gender segregation, and legal discrimination that characterize the Islamic Republic would face immediate challenges. Yet Iranian society itself remains divided on these issues—urban secular elites versus traditional provincial communities. Navigating these divisions without triggering backlash would test any new government.

The Shadow of Sanctions and the Price of Defiance

The cruel irony of Iran’s economic crisis is that it represents precisely the outcome Western sanctions architects intended: economic pressure so severe it forces either government capitulation or popular revolt. Yet sanctions’ human cost—impoverished civilians, medical shortages, brain drain—has not translated into policy change from Tehran’s leadership, which has weathered pressure through repression and distributing pain downward.

Whether sanctions have been strategic success or moral failure remains contested. Proponents argue they prevented war while constraining Iran’s nuclear program and regional activities. Critics point to humanitarian suffering and the strengthening of hardliners who use sanctions as nationalist rallying cry. What’s clear is that maximum pressure created maximum desperation without achieving stated objectives of behavioral change or negotiated settlement.

The Biden administration’s limited sanctions relief proved insufficient to reverse economic decline, while Trump’s return to office in 2025 dashed hopes for meaningful negotiations. Iran’s government, convinced that Western demands are designed for regime change regardless of concessions, has doubled down on resistance. The nuclear program has advanced to alarming levels—near weapons-grade enrichment without actual weaponization—creating a permanent crisis that neither side can resolve without political courage absent in Tehran and Washington.

Conclusion: The Economics of Endurance and Uncertainty

Iran’s economic troubles run deeper than currency fluctuations or even sanctions—they reflect a regime that has sacrificed prosperity for ideological purity and elite enrichment. The protests of 2025 were suppressed, but the economic grievances that fueled them remain unresolved and worsening. The question is no longer whether Iran’s economy is troubled, but whether it can remain troubled indefinitely without triggering irreversible political consequences.

The elevation of figures like Reza Pahlavi indicates that Iranians are psychologically preparing for possibilities once unthinkable. Yet regime change carries profound risks alongside potential rewards. The Islamic Republic has proven remarkably resilient, surviving war, sanctions, and periodic unrest for 45 years. Its security apparatus remains powerful, its ideological supporters still numerous enough to matter, and its regional influence a source of leverage.

What happens next depends on variables impossible to predict: Will oil prices surge or crash? Will the Trump administration pursue military confrontation or transactional diplomacy? Will Iran’s youth overcome fear to mount sustained resistance, or will repression and exhaustion prevail? Can the regime implement reforms sufficient to relieve pressure without triggering demands for fundamental change?

For the shopkeeper in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar, these geopolitical abstractions matter less than the daily calculus of survival. He measures the crisis not in percentage points but in customers who can no longer afford pistachios they once bought by the kilo. Economic troubles, he knows from experience, can be endured for a long time—until suddenly they cannot. The question for Iran in 2026 is which side of that inflection point the country stands on.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

Digital Economy as Pakistan’s Next Economic Doctrine: A Growth Debate Trapped in the Past

Understanding the Digital Economy: More Than a Sector, a System

There is a persistent category error at the heart of Pakistan’s economic policymaking. Officials speak of the “digital economy” the way an earlier generation spoke of textiles or agriculture — as a discrete sector, a line on an export ledger, a portfolio to be managed rather than a platform to be built. This confusion is not merely semantic. It shapes budget allocations, regulatory frameworks, institutional mandates, and, ultimately, the trajectory of a nation of 240 million people standing at a crossroads between chronic underdevelopment and a genuinely plausible economic transformation.

The digital economy, properly understood, is not a sector. It is the operating system upon which all modern economic activity increasingly runs. It encompasses the digitisation of production processes, the datafication of consumer behaviour, the platformisation of labour markets, and the emergence of knowledge as the primary factor of production. When the World Bank’s April 2025 Pakistan Development Update frames digital transformation as Pakistan’s most credible path toward export competitiveness and sustained growth, it is not advocating for a bigger IT park in Islamabad. It is arguing for a wholesale reimagining of what the Pakistani economy produces, and for whom.

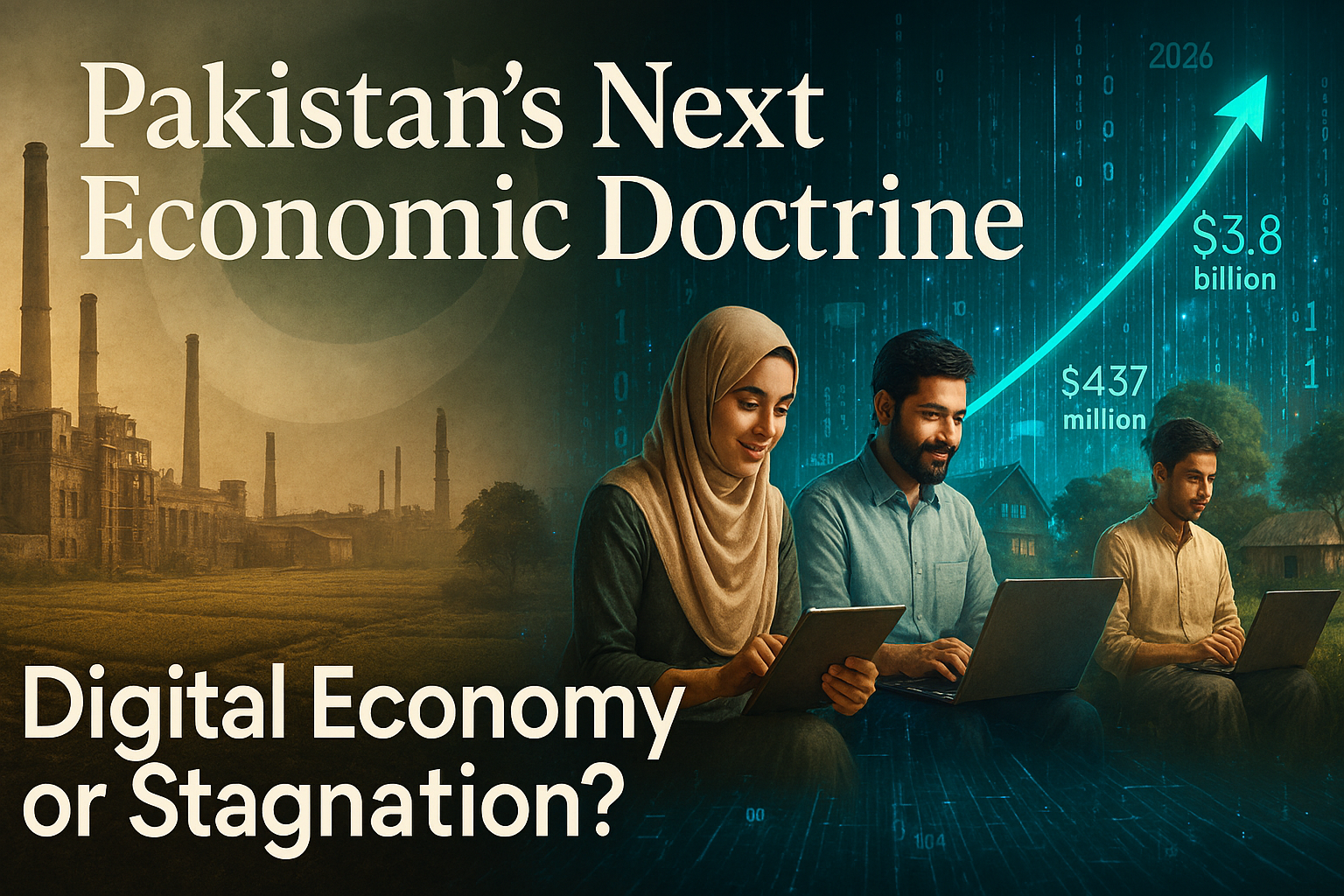

That reimagining has begun — tentatively, unevenly, and against considerable institutional resistance. The numbers, for once, are genuinely exciting. Pakistan IT exports reached $3.8 billion in FY2024–25, with the momentum building sharply into the current fiscal year: $2.61 billion in IT and ICT exports were recorded between July and January of FY2025–26, a 19.78% increase year-on-year, according to data released by the Pakistan Software Export Board (PSEB). December 2025 delivered a record single-month figure of $437 million — the highest in the country’s history. These are not marginal gains. They are signals of structural potential.

The question this analysis addresses is whether Pakistan possesses the institutional architecture, policy coherence, and political will to convert those signals into doctrine — or whether it will allow a historic opportunity to dissolve into the familiar entropy of short-termism, infrastructure neglect, and regulatory dysfunction.

Pakistan’s Emerging Digital Base: A Foundation That Defies the Headlines

The pessimistic narrative about Pakistan — fiscal crisis, security fragility, political instability — dominates international discourse and obscures a digital demographic reality that is, by most comparative metrics, extraordinary. Pakistan now has 116 million internet users, with penetration reaching 45.7% in early 2025 and accelerating. The PBS Household Survey 2024–25 found that over 70% of households have at least one member online, with individual usage approaching 57% of the adult population. Against the baseline of five years ago, this represents a compression of the connectivity timeline that took wealthier economies a generation to traverse.

Mobile is the primary vector. Pakistan’s 190 million mobile connections and 142 million broadband subscribers — figures corroborated by GSMA’s State of Mobile Internet Connectivity — reflect a population that has leapfrogged fixed-line infrastructure entirely and gone straight to smartphone-mediated internet access. Smartphone ownership has surged with the proliferation of affordable Chinese handsets, democratising access in a way that no government programme could have engineered.

The identity infrastructure is strengthening in parallel. NADRA’s digital ID system now covers the vast majority of the adult population, providing the authentication backbone without which digital financial services, e-commerce, and government-to-citizen digital delivery cannot scale. The State Bank of Pakistan’s (SBP) digital payments architecture — including the Raast instant payment system — has facilitated a measurable shift in transaction behaviour, particularly among younger urban cohorts.

What Pakistan has, in other words, is a digital base: not yet a digital economy, but the preconditions for one. The distinction is critical. A digital base is necessary but not sufficient. Converting it into export-generating, job-creating, productivity-enhancing economic activity requires deliberate policy architecture — something Pakistan has so far delivered only in fragments.

Geography Is Being Rewritten: The Location Dividend

For most of economic history, geography was fate. A landlocked country, a country far from major shipping lanes, a country without navigable rivers or natural harbours faced structural disadvantages that compounded over centuries. Pakistan’s geographic position — bordering Afghanistan, Iran, India, and China, with access to the Arabian Sea — has historically been as much a source of strategic anxiety as economic opportunity.

The digital economy rewrites this calculus. In knowledge-intensive digital services, physical location is increasingly irrelevant to market access. A software engineer in Lahore can serve a fintech client in Frankfurt. A data scientist in Karachi can work for a healthcare analytics firm in Houston. A UX designer in Peshawar can deliver to a product team in Singapore. The barriers that historically constrained Pakistani talent to domestic labour markets — or forced emigration — are structurally dissolving.

This is the location dividend: the ability to monetise Pakistani human capital in global markets without the friction costs of physical migration. It is a form of comparative advantage that requires no natural resources, no preferential trade agreements, and no proximity to wealthy consumer markets. It requires only talent, connectivity, and institutional conditions that allow value to flow across borders.

Pakistan’s digital economy growth model, at its most ambitious, is predicated on precisely this arbitrage: world-class technical skill delivered at emerging-market cost, routed through digital platforms, and paid in foreign exchange. The macroeconomic implications — for the current account, for foreign reserves, for wage convergence — are profound. The World Bank’s Digital Pakistan: Economic Policy for Export Competitiveness report identifies this services export channel as among the most scalable dimensions of the country’s growth potential.

The geography dividend is real. The question is whether Pakistan can build the institutional infrastructure to fully claim it.

The Freelancer Paradox: Scale Without Structure

Perhaps nowhere is the tension between Pakistan’s digital potential and its institutional constraints more vividly illustrated than in its freelance economy. The headline numbers are startling. Pakistan’s 2.37 million freelancers — an estimate from the Asian Development Bank (ADB) — generate a scale of digital services exports that places the country consistently in the top three to four globally on platforms including Upwork, Fiverr, and Toptal. Freelance earnings in H1 FY2025–26 reached $557 million, a 58% year-on-year increase from $352 million — a growth rate that no traditional export sector can approach.

This is the “freelancer paradox Pakistan” faces: enormous revealed comparative advantage, operating almost entirely outside formal policy architecture. The vast majority of Pakistan’s freelancers work without contracts, without access to institutional credit, without social protection, and without the kind of professional certification or dispute resolution frameworks that would allow them to move up the value chain from commodity task completion to complex, high-margin engagements.

The income ceiling is real and consequential. A Pakistani freelancer completing logo designs or basic data entry tasks on Fiverr earns at the low end of the global digital labour market. The same talent, operating through a structured agency model, with portfolio development support, client management training, and access to premium platforms, could command rates three to five times higher. The gap between what Pakistan’s freelance workforce earns and what it could earn is, effectively, a measure of what institutional neglect costs.

The foreign exchange dimension compounds the problem. Payments routed through platforms like PayPal — where availability for Pakistani users remains restricted — or through informal hawala networks, often bypass the formal banking system entirely. The SBP has made progress in facilitating formal remittance channels, but significant friction remains. Pakistan freelance exports are growing despite the system, not because of it.

A comprehensive Pakistan digital economy doctrine must address the freelancer economy not as an afterthought but as a strategic asset requiring dedicated institutional support: access to formal banking, skills certification, contract facilitation, and platform-level advocacy.

Infrastructure Reliability as Export Competitiveness: The Invisible Tax

Ask any Pakistani software engineer working on an international client project what their single biggest operational constraint is, and the answer is rarely regulatory. It is the power cut that interrupted a client call. It is the bandwidth throttling that corrupted a code repository push. It is the VPN restriction that prevented access to a cloud development environment. These are not edge cases. They are the daily texture of doing business in Pakistan’s digital economy.

Infrastructure reliability is not a background variable. In digital services exports, it is export competitiveness. A Pakistani IT firm competing against Indian, Ukrainian, or Filipino counterparts is not merely selling talent — it is selling reliable, on-time, high-quality delivery. A single missed deadline caused by a grid outage can cost a client relationship worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. Cumulatively, infrastructure unreliability functions as an invisible tax on Pakistan’s digital exports Pakistan is uniquely ill-positioned to afford.

The electricity crisis is the most acute dimension of this problem. Pakistan’s circular debt overhang — exceeding Rs. 2.4 trillion — continues to produce load-shedding that falls hardest on small businesses and home-based workers, who constitute the backbone of the freelance and micro-enterprise digital economy. Large IT firms in tech parks have access to backup generation; individual freelancers in Multan or Faisalabad do not.

Broadband quality is the second constraint. Pakistan’s average fixed broadband speed, while improving, remains well below regional competitors. Mobile data costs have declined, but network congestion in urban cores during peak hours frequently degrades the quality of experience to levels incompatible with professional digital work. The GSMA has consistently highlighted last-mile connectivity gaps as the primary barrier to realising Pakistan’s mobile internet dividend.

A credible Pakistan digital economy doctrine must treat infrastructure investment — in power stability, fibre optic expansion, and spectrum management — not as a public works programme but as export infrastructure, directly analogous to port expansion for goods trade.

Cyber Risks and the Trust Deficit: The Hidden Vulnerability

Digital economies are only as robust as the trust that underpins them. Trust operates at multiple levels: consumer trust in digital financial services, business trust in cloud infrastructure, investor trust in data governance frameworks, and international partner trust in Pakistan’s regulatory environment. On all of these dimensions, Pakistan faces a significant trust deficit that constrains the Pakistan digital economy growth trajectory.

Cybersecurity incidents affecting Pakistani financial institutions have multiplied. The banking sector has faced card data breaches, phishing campaigns targeting mobile banking users, and SIM-swap fraud at scale. The Pakistan Telecommunication Authority’s (PTA) record of internet shutdowns and platform restrictions — including prolonged access restrictions to major social media platforms during periods of political tension — has created a perception among international digital businesses that Pakistan’s internet governance is unpredictable.

This unpredictability carries a direct economic cost. International clients contracting Pakistani firms for sensitive data processing work — healthcare records, financial data, personal information — conduct due diligence on the regulatory and security environment. A country with a history of arbitrary platform restrictions and limited data protection enforcement does not inspire confidence for high-value data contracts.

Pakistan’s Personal Data Protection Bill, in legislative limbo for several years, represents the most visible symptom of this institutional gap. Without a credible, enforced data protection framework, Pakistan cannot credibly bid for the categories of digital services work — cloud processing, AI training data, health informatics — where the highest margins and fastest growth lie. Closing this gap is not merely a legal formality; it is a prerequisite for moving up the digital value chain.

Institutional Constraints and Policy Incoherence: The Structural Brake

Pakistan’s digital economy governance is fragmented across a proliferation of bodies — the Ministry of IT and Telecom (MoITT), PSEB, PTA, the National Information Technology Board (NITB), provincial ICT authorities, and the Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) — with overlapping mandates, inconsistent coordination, and chronic under-resourcing. This fragmentation is not accidental; it reflects the accumulation of institutional layering that characterises Pakistan’s economic governance more broadly.

The policy incoherence is manifested in contradictions that would be almost comic if they were not so economically costly. Pakistan simultaneously promotes itself as a top destination for IT outsourcing while maintaining VPN restrictions that its own IT workers require to access client systems. It celebrates freelance export earnings while allowing the forex payment infrastructure for those earnings to remain dysfunctional. It announces ambitious digital skills programmes while underfunding the higher education institutions that produce the graduates those programmes are supposed to train.

The Pakistan IT exports 2026 growth trajectory — impressive as it is — is occurring largely in spite of, rather than because of, this governance architecture. The question for policymakers is not whether the current momentum can continue; it can, for a time, on the basis of demographic dividend and individual entrepreneurial energy alone. The question is whether that momentum can be compounded into the kind of structural transformation that moves Pakistan from an exporter of digital labour to an exporter of digital products and platforms.

That transition requires a qualitatively different institutional environment: one capable of regulating without strangling, facilitating without distorting, and investing at the horizon of a decade rather than the cycle of a fiscal year.

Digital Sovereignty and Platform Dependency: The Strategic Dimension

Beneath the growth narrative lies a geopolitical and strategic question that Pakistan’s digital economy debate has been slow to engage: the question of digital sovereignty Pakistan must navigate. As Pakistani businesses and individual workers increasingly integrate into global digital platform ecosystems — Upwork, Fiverr, AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure — they gain access to markets, infrastructure, and tools that would be impossible to replicate domestically. They also incur structural dependencies that carry long-term risks.

Platform dependency is not a uniquely Pakistani problem. Every country that has embraced the global digital economy faces some version of this tension. But for Pakistan, the risks are heightened by the country’s limited regulatory leverage, its absence from the standard-setting bodies that govern international digital trade, and the concentration of critical digital infrastructure in the hands of a small number of US-headquartered technology corporations.

The practical implications are significant. When a major freelance platform adjusts its fee structure or payment policies, Pakistani freelancers — who have no collective bargaining mechanism, no government-backed alternative platform, and no domestic digital marketplace of comparable scale — absorb the consequences. When a cloud provider raises prices or discontinues a service, Pakistani startups that have built their infrastructure on that provider face switching costs that can be existential.

Digital sovereignty does not mean autarky. It means building sufficient domestic digital capacity — in cloud infrastructure, in payment systems, in data storage, in platform development — to maintain meaningful optionality. It means participating in the governance of the global digital economy rather than passively receiving its terms. It means developing the regulatory expertise to negotiate with platform giants on terms that protect Pakistani economic interests.

This is a long-game strategic agenda, not a short-cycle policy fix. But without it, Pakistan’s Pakistan digital economy growth risks being permanently extractive — generating value that is captured elsewhere.

Government as Digital Market Creator: The Enabling State

One of the most durable insights from the comparative study of digital economy development — South Korea, Estonia, Singapore, Rwanda — is that the private sector alone does not build digital economies. Governments create the conditions: the infrastructure, the standards, the skills pipeline, the procurement signals, and the regulatory certainty without which private investment cannot take root at scale.

Pakistan’s government has the opportunity — and, given the fiscal constraints, the obligation — to be a strategic market creator rather than a passive regulator. Government digitalisation is not merely an efficiency play; it is a demand-side signal to the domestic digital industry. When the government digitises land records, health systems, tax administration, and public procurement, it creates contract opportunities for Pakistani IT firms, validates the commercial viability of digital solutions, and builds the reference clients that domestic companies need to compete internationally.

The PSEB’s facilitation role — connecting international clients with Pakistani IT firms, providing export certification, and advocating for payment infrastructure improvements — represents the embryo of a more active industrial policy. The SIFC’s mandate, if properly operationalised for the digital sector, could provide the high-level coordination that has been missing. But these institutions need resources, autonomy, and political backing to function at the scale the opportunity demands.

The most immediate lever available is public digital procurement: a committed pipeline of government IT contracts awarded to domestic firms under transparent, merit-based processes. This single policy — properly designed and consistently executed — could do more to develop Pakistan’s digital industry than any number of incubator programmes or innovation fund announcements.

From Factor-Driven to Knowledge-Driven Economy Pakistan: The Structural Leap

Pakistan’s economic growth model has, for most of its history, been factor-driven: growth generated by deploying more labour, more land, more capital, in sectors with relatively low productivity — agriculture, low-complexity manufacturing, commodity exports. The digital economy represents the most credible pathway to a fundamentally different model: one in which growth is driven by increasing productivity, accumulating human capital, and generating returns from knowledge rather than from raw inputs.

The knowledge-driven economy Pakistan needs is not a distant aspiration. The ingredients exist, in nascent form: a young population with demonstrated aptitude for digital skills, universities producing engineers and computer scientists at scale, a diaspora with global networks and capital, and a domestic entrepreneurial ecosystem generating startups in fintech, healthtech, agritech, and edtech that are beginning to attract international venture investment.

The transition from factor-driven to knowledge-driven growth is not automatic or inevitable. It requires deliberate investment in research and development, in higher education quality, in intellectual property protection, and in the kind of long-term institutional stability that allows firms to make multi-year investment commitments. Pakistan’s R&D expenditure as a share of GDP remains among the lowest in Asia — a structural constraint that no amount of IT export promotion can overcome if sustained.

The ADB’s research on Pakistan freelancers earnings and digital service exports consistently emphasises that the earnings ceiling for task-based freelance work is far lower than for product-based or IP-based digital exports. Moving Pakistani digital workers up this value curve — from executing tasks to building products, from selling hours to licensing software — is the central challenge of knowledge economy transition.

Policy Priorities for a Digital Doctrine: What Must Be Done

A credible Pakistan digital economy doctrine for the period to 2030 requires six interlocking policy commitments, each necessary but none sufficient in isolation.

First, infrastructure as export policy. Pakistan must treat reliable electricity supply and high-quality broadband as preconditions for digital export competitiveness, not as welfare goods. This means prioritising digital economic zones with guaranteed power supply, accelerating fibre optic backbone expansion into secondary cities, and reducing spectrum costs for business-grade mobile broadband.

Second, the forex plumbing must be fixed. The SBP must complete the liberalisation of digital payment channels, enabling Pakistani freelancers and digital firms to receive, hold, and deploy foreign currency earnings without the friction that currently drives significant volumes into informal channels. Every dollar that flows through informal networks is a dollar that does not build Pakistan’s foreign reserves or generate formal tax revenue.

Third, data protection legislation must be enacted and enforced. The Personal Data Protection Bill must be passed in a form that meets international standards — not as a regulatory box-ticking exercise, but as a genuine market access instrument. Pakistan cannot compete for high-value data services contracts without credible data governance.

Fourth, skills investment must match ambition. Pakistan’s Pakistan IT exports 2026 targets require a quantum expansion of the technical skills pipeline — not through low-quality short courses, but through sustained investment in computer science education at the tertiary level, curriculum modernisation, and industry-academia partnerships that ensure graduates enter the workforce with market-relevant capabilities.

Fifth, institutional consolidation. The fragmented governance architecture for the digital economy must be rationalised. A single, adequately resourced Digital Economy Authority — with a clear mandate, cross-ministerial coordination powers, and direct accountability to the Prime Minister — would reduce the transaction costs of doing business in Pakistan’s digital sector by orders of magnitude.

Sixth, a digital sovereignty strategy. Pakistan needs a national cloud strategy, a digital platform policy, and active participation in international digital trade negotiations. These are not luxury items for a mature digital economy; they are foundational choices that, once deferred, become progressively more expensive to make.

Conclusion: A Decisive Economic Choice

Pakistan’s Pakistan digital economy moment is real, and it is now. The combination of demographic scale, demonstrated digital talent, accelerating connectivity, and record IT and freelance export earnings constitutes a rare convergence of factors that, in other economies, has served as the launching pad for durable structural transformation.

But potential is not destiny. History is littered with countries that glimpsed the digital transformation horizon and then allowed institutional inertia, political short-termism, and infrastructure neglect to ensure they never reached it.

The debate Pakistan is currently having about its digital economy is, at its deepest level, a debate about what kind of economic future the country chooses to construct. The old paradigm — commodity exports, remittances, periodic IMF bailouts, growth that barely keeps pace with population — has delivered recurrent crisis and chronic underinvestment in human capital. The digital paradigm offers something genuinely different: a pathway to prosperity grounded in the one resource Pakistan has in abundance, its people, and their capacity for knowledge work in a globally connected economy.

Digital sovereignty Pakistan must claim is not merely about technology. It is about economic agency — the ability to participate in the global economy on terms that capture value domestically rather than exporting it. Every reform deferred, every institutional bottleneck left unaddressed, every dollar that flows through informal channels rather than the formal banking system, is a cost Pakistan cannot afford.

The choice between a Pakistan whose digital economy remains a promising footnote and one whose Pakistan digital economy growth becomes the defining story of the coming decade is not a technical question. It is a political one. And it must be answered decisively — before the window that demographics, technology, and global market demand have opened begins, once again, to close.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

Top 10 Countries with the World’s Strongest Currencies in 2026 — Ranked & Analysed

Discover the world’s strongest currencies in 2026 — ranked by exchange value, economic backing & purchasing power. From Kuwait’s $3.27 dinar to the Swiss franc’s unmatched stability, the definitive guide.

Where Money Is Worth More Than You Think

There is a question that unsettles most travellers the moment they land at an unfamiliar airport and squint at a currency board: how much, exactly, is this money worth? The instinct is to reach for the US dollar as a yardstick — to ask, almost reflexively, whether the local note in your hand represents more or less than a single greenback. That reflex is understandable. The dollar remains, by a vast margin, the most traded and most held reserve currency on the planet. But it is not the strongest.

That distinction belongs to a small Gulf emirate whose population would fit comfortably inside greater Manchester, and whose currency has quietly dominated every global ranking for more than two decades. It is joined on the podium by neighbours whose names rarely make mainstream financial headlines, and by a landlocked Alpine republic whose monetary tradition has become almost mythological in global finance circles.

Currency strength is, of course, a deceptively complicated concept. A high nominal exchange rate — the number of US dollars one unit of a foreign currency can buy — is the most intuitive measure, but it captures only part of the picture. Purchasing power parity (PPP), the stability of the issuing central bank, inflation history, current-account balances, and forex reserve depth all feed into a fuller assessment of monetary credibility. The rankings below attempt to honour that complexity: they are ordered primarily by nominal value against the USD as of early March 2026, but enriched with structural and macroeconomic context at every step.

For travellers, the implications are vivid and practical: a strong home currency means your holiday budget stretches further in weaker-currency markets. For investors, it signals where monetary policy is disciplined, inflation is tamed, and capital preservation is most plausible. For economists, it is a mirror of a nation’s fiscal choices — and occasionally its geological luck.

Here, then, is the definitive ranking of the world’s strongest currencies in 2026.

Methodology: How We Ranked the World’s Strongest Currencies

Ranking currencies by strength is not a single-variable exercise. Our methodology combines four weighted criteria:

1. Nominal exchange rate vs. USD (primary weight: 50%) — the most cited metric globally; how many US dollars one unit of the currency buys as of early March 2026.

2. Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) and domestic price stability (25%) — drawing on the IMF World Economic Outlook database and World Bank ICP data to assess what each currency actually buys at home.

3. Central bank credibility, forex reserves, and current-account balance (15%) — using BIS data, central bank publications, and IMF Article IV consultations.

4. Long-term inflation track record and monetary regime stability (10%) — a currency pegged rigidly to the dollar for decades earns credit for predictability; a currency that preserved purchasing power across multiple global crises earns even more.

Geographic territories whose currencies are pegged 1:1 to a sovereign currency (Gibraltar Pound, Falkland Islands Pound) are noted but not separately ranked; they effectively mirror their parent currency’s fundamentals.

The World’s Strongest Currencies in 2026: Comparative Table

| Rank | Country / Territory | Currency | Code | Value vs. USD (Mar 2026) | 1-Year Change | Exchange Regime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kuwait | Kuwaiti Dinar | KWD | ≈ $3.27 | Stable (±0.5%) | Managed basket peg |

| 2 | Bahrain | Bahraini Dinar | BHD | ≈ $2.66 | Stable (fixed) | Hard USD peg |

| 3 | Oman | Omani Rial | OMR | ≈ $2.60 | Stable (fixed) | Hard USD peg |

| 4 | Jordan | Jordanian Dinar | JOD | ≈ $1.41 | Stable (fixed) | Hard USD peg |

| 5 | United Kingdom | Pound Sterling | GBP | ≈ $1.26 | −1.8% | Free float |

| 6 | Cayman Islands | Cayman Dollar | KYD | ≈ $1.20 | Stable (fixed) | Hard USD peg |

| 7 | Switzerland | Swiss Franc | CHF | ≈ $1.13 | +2.1% | Managed float |

| 8 | European Union | Euro | EUR | ≈ $1.05 | −1.2% | Free float |

| 9 | Singapore | Singapore Dollar | SGD | ≈ $0.75 | +1.4% | NEER-managed |

| 10 | United States | US Dollar | USD | $1.00 | Benchmark | Free float |

Exchange rates are indicative mid-market values, early March 2026. Sources: Central Bank of Kuwait, Central Bank of Bahrain, Central Bank of Oman, Bloomberg, Reuters.

#10 — United States: The Dollar That Rules the World (Even When It Isn’t the Strongest)

USD/USD: 1.00 | Reserve share: ~56% of global FX reserves (IMF COFER, mid-2025)

It would be intellectually dishonest to construct any list of monetarily significant currencies without beginning — or in this case, ending — with the US dollar. Technically ranked tenth by nominal exchange rate, the dollar’s omission from any strong-currency discussion would be absurd. It is the global reserve currency, the denomination of roughly 90% of all international foreign-exchange transactions, and the standard against which every other currency on this list is measured.

The dollar’s structural power derives not from its face value but from the depth and liquidity of US capital markets, the legal enforceability of US-dollar-denominated contracts, and the unrivalled network effects that come from decades of institutional entrenchment. When the world is frightened — by a banking crisis, a pandemic, or a geopolitical rupture — capital flows into dollars, not away from them. That is the ultimate credential.

The Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate-hiking cycle of 2022–2023 temporarily turbocharged the greenback to multi-decade highs. Since then, a gradual easing cycle has modestly softened the dollar index (DXY), which hovered around the mid-100s range in early 2026. Yet its dominance in global trade invoicing and central bank reserves remains essentially unchallenged.

Travel angle: For American travellers abroad, the dollar’s reserve status means widespread acceptance and generally favourable conversion, particularly in emerging markets. The caveat: in the Gulf states above the dollar on this list, the local currencies are pegged to the dollar, so there is no exchange-rate advantage — the mathematics are already baked in.

#9 — Singapore: The Asian Precision Instrument

SGD/USD: ≈ 0.75 | Inflation: ~2.1% (MAS, 2025) | Current account: strong surplus

Singapore manages its currency with the kind of institutional exactitude one might expect from a city-state that has spent sixty years treating good governance as a competitive export. The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) does not set interest rates in the conventional sense; it manages the Singapore dollar’s value against an undisclosed basket of currencies through a “nominal effective exchange rate” (NEER) policy band — a mechanism that gives it enormous flexibility to use currency appreciation as an anti-inflation tool.

The result is a currency that, while not high in nominal USD terms, has consistently outperformed peers in Asia on purchasing-power stability. Singapore’s AAA sovereign credit rating (Standard & Poor’s, Fitch), perennially current-account surplus, and status as Asia’s pre-eminent financial hub all feed into the SGD’s credibility premium. The SGD appreciated modestly against the dollar in 2025 as MAS maintained a slightly appreciating NEER slope — a deliberate policy response to residual imported inflation from elevated global commodity prices.

For investors, the Singapore dollar is one of very few Asian currencies worth holding as a diversification tool in a hard-currency portfolio. For travellers from weaker-currency nations, Singapore’s cost of living will feel punishing — this is, after all, consistently one of the world’s most expensive cities. But that high cost is the precise reflection of the currency’s strength.

#8 — The Euro: Collective Strength, Individual Tensions

EUR/USD: ≈ 1.05 | ECB deposit rate: 2.25% (as of Feb 2026) | Eurozone GDP growth: ~0.9% (IMF 2026 forecast)

The euro is the world’s second most traded currency and the reserve currency of choice after the dollar, held in roughly 20% of global central bank foreign exchange portfolios. It represents the collective monetary credibility of twenty nations — a fact that is simultaneously its greatest source of strength and its most persistent structural vulnerability.

The European Central Bank’s prolonged rate-hiking campaign of 2022–2024 was executed with more determination than many in financial markets expected, and it produced results: eurozone core inflation fell from its 2022 peak of above 5% to below 2% by mid-2025, a trajectory that restored considerable credibility to the ECB’s inflation-targeting framework. The subsequent easing cycle has been cautious; the deposit rate stood at approximately 2.25% in early 2026, a level the ECB’s governing council has characterised as still moderately restrictive.

The euro’s Achilles heel remains the fiscal divergence between its member states. Germany’s near-recessionary growth in 2024–2025, combined with France’s persistent budget deficit challenges and Italy’s elevated debt-to-GDP ratio (above 135%), keeps sovereign risk premia alive in bond markets and periodically unsettles the currency. Still, the Eurozone’s aggregate current-account position is in surplus, and the ECB’s “Transmission Protection Instrument” — its bond-buying backstop — has effectively capped the threat of another existential sovereign debt crisis for now.

Travel angle: For USD- or GBP-holders, the euro’s current rate around $1.05 represents a relatively modest barrier. Western European travel remains expensive not because of the exchange rate but because of local price levels — a function of high wages and robust social provision rather than currency manipulation.

#7 — Switzerland: The Safe-Haven That Earned Its Reputation

CHF/USD: ≈ 1.13 | SNB policy rate: 0.25% | Inflation: ~0.3% (SNB, Feb 2026) | Current account surplus: ~9% of GDP

If the Kuwaiti dinar wins on headline exchange rate, the Swiss franc wins on something arguably more impressive: institutional longevity. Switzerland has managed its monetary affairs with such consistent discipline that the franc has preserved real purchasing power across multiple global crises, two world wars (in which Switzerland remained neutral), the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, the 2008 global financial crisis, and the COVID-19 shock. That record of monetary continuity, spanning more than 175 years since the franc’s introduction in 1850, is essentially without parallel among modern fiat currencies.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) operates with an independence and a long-termism that remains the envy of its peers. Its mandate — price stability, defined as annual CPI inflation of 0–2% — has been met with remarkable consistency. Swiss inflation in early 2026 stood at approximately 0.3%, one of the lowest in the developed world, and a reflection of the SNB’s willingness in previous years to tolerate the economic pain of a strong franc (which reduces import costs and anchors domestic prices) rather than engineer currency weakness for short-term competitiveness.

Switzerland’s current-account surplus, running at roughly 9% of GDP, reflects a country that consistently exports more value than it imports — in pharmaceuticals, precision machinery, financial services, and, of course, the world’s most trusted watches. That structural external surplus is a bedrock of franc credibility.

The SNB’s policy rate stood at 0.25% in early 2026 — low, because very low inflation means there is no need for restrictive policy. The franc’s strength is not conjured by high interest rates attracting hot capital; it is built on structural surpluses, institutional credibility, and a century and a half of monetary conservatism.

Investor angle: The CHF remains one of the most reliable safe-haven plays in global markets. When geopolitical risk flares — and it has consistently done so across 2024–2026 — capital rotates into the franc. Its appreciation during such episodes is the price of insurance.

#6 — Cayman Islands: Offshore Stronghold, Surprising Currency

KYD/USD: 1.20 (fixed since 1974) | Sector: International financial centre

The Cayman Islands may be small — approximately 65,000 residents across three Caribbean islands — but their currency punches well above its geographic weight. The Cayman Islands dollar has been pegged to the US dollar at a fixed rate of 1.20 since 1974, a peg that has held without interruption for over five decades.

The peg is sustainable because the Cayman Islands economy generates exceptional foreign currency inflows. As one of the world’s leading offshore financial centres, the Cayman Islands hosts thousands of hedge funds, private equity vehicles, structured finance vehicles, and the regional offices of major global banks. This financial infrastructure creates persistent capital inflows that underpin the peg’s credibility without recourse to the kind of oil revenues that sustain Gulf currencies.

The absence of direct taxation — no corporate tax, no income tax, no capital gains tax — also functions as a structural attractor for international capital, further reinforcing demand for the local currency.

For travellers, the Cayman Islands’ combination of strong currency and luxury resort economy makes it one of the Caribbean’s more expensive destinations. But that premium reflects something real: it is, genuinely, one of the most politically stable and financially sophisticated jurisdictions in the Western Hemisphere.

#5 — United Kingdom: History’s Most Enduring Major Currency

GBP/USD: ≈ 1.26 | Bank of England base rate: 4.25% (Feb 2026) | UK GDP growth forecast: 1.3% (IMF 2026)

The pound sterling has a plausible claim to being the world’s oldest currency still in active use. Predating the United States by more than a millennium in its earliest forms, sterling carries the weight of institutional memory — and the scars of historical crises, from the 1976 IMF bailout to Black Wednesday in 1992 to the post-Brexit adjustment of 2016. That the pound has navigated all of this and still trades above $1.25 says something significant about the resilience of UK monetary institutions.

The Bank of England, established in 1694, has been on a cautious easing path since mid-2024, reducing its base rate from the post-pandemic peak of 5.25% to 4.25% by early 2026 as UK inflation — which ran brutally hot in 2022–2023 — returned closer to the 2% target. Core CPI had moderated to approximately 2.7% by early 2026, still slightly elevated but no longer the acute political crisis it was.

The UK’s economic structure — highly service-oriented, with the City of London representing one of the world’s two or three most important financial centres — means sterling’s value has always been intimately connected to confidence in UK financial governance. Post-Brexit trade frictions have not destroyed that confidence, though they have permanently restructured some trade flows and depressed productivity estimates.

Travel angle: Sterling’s strength makes UK residents among the best-positioned travellers in the world, particularly when visiting North Africa, South-East Asia, or Eastern Europe, where exchange rate differentials translate into substantial purchasing power advantages. The pound buys significantly more in emerging markets today than it did five years ago.

#4 — Jordan: Strength Without Oil

JOD/USD: 1.41 (fixed peg) | Inflation: ~2.8% | IMF programme: Extended Fund Facility (ongoing)

Jordan’s presence in the top four is the most intellectually interesting entry on this list, because it is a standing refutation of the narrative that strong currencies require oil. Jordan has no significant hydrocarbon reserves. Its economy depends on phosphate exports, manufacturing, services, remittances from a large diaspora, foreign aid — primarily from the United States, Saudi Arabia, and the EU — and its strategic geopolitical position at the intersection of three continents and several of the region’s most complex political dynamics.

The Jordanian dinar has been pegged to the US dollar at a fixed rate of 0.709 JOD per dollar (implying approximately $1.41 per dinar) since 1995, a commitment the Central Bank of Jordan has maintained through multiple regional crises — the 2003 Iraq war, the 2011 Arab Spring, the Syrian refugee crisis (Jordan hosts one of the world’s largest refugee populations relative to its size), and the ongoing regional tensions of 2024–2025.

The peg’s credibility is purchased at a fiscal cost: Jordan must maintain sufficient foreign exchange reserves to defend it, which constrains domestic monetary flexibility and requires disciplined fiscal policy, often in collaboration with IMF structural adjustment programmes. That discipline — painful as it has periodically been — is precisely what makes the dinar’s high nominal value sustainable.

Investor angle: The JOD peg makes Jordan one of the more predictable currency environments in the Middle East, which partly explains why Amman has attracted meaningful foreign direct investment in logistics, technology, and pharmaceuticals in recent years.

#3 — Oman: The Prudent Gulf State

OMR/USD: 2.60 (fixed peg) | Oil production: ~1 mbpd | Moody’s rating: Ba1

The Omani rial’s fixed exchange rate of 2.6008 USD per rial has been unchanged for decades — a testament to the consistency of Oman’s monetary framework. Like its Gulf neighbours, Oman’s currency strength is anchored in hydrocarbon wealth, but the sultanate has pursued a more earnest diversification agenda than some of its neighbours, with meaningful investment in tourism, logistics, fisheries, and renewable energy under its Vision 2040 framework.

Oman’s fiscal position has improved markedly since the turbulence of the low-oil-price years of 2015–2016, when the country ran significant budget deficits and accumulated external debt. Higher oil prices in the early 2020s rebuilt fiscal buffers, and the government has since pursued subsidy reform and revenue diversification with greater determination than before. Moody’s upgraded Oman’s sovereign credit in 2023, reflecting improving balance-of-payment dynamics.

The Central Bank of Oman manages the currency through a currency board-style arrangement, holding sufficient USD reserves to back every rial in circulation at the fixed rate. This mechanistic commitment is what gives the OMR its enviable nominal stability — and what keeps it permanently ranked as the world’s third most valuable currency by exchange rate.

Travel angle: Oman’s strong currency, combined with its emergence as a luxury-eco-tourism destination, means it is not an especially cheap place to visit. But for holders of stronger currencies like the pound or the Swiss franc, the arithmetic is favourable — and Oman’s landscapes, from the Musandam fjords to the Wahiba Sands, make the cost worthwhile.

#2 — Bahrain: The Gulf’s Financial Hub

BHD/USD: 2.659 (fixed peg since 1980) | Financial sector: ~17% of GDP | Moody’s: B2

Bahrain’s dinar has been fixed to the US dollar at 0.376 BHD per dollar — implying approximately $2.66 per dinar — since 2001, maintaining an unchanged peg for a quarter century. That consistency, in a region not historically associated with monetary conservatism, is itself a form of credibility.

Bahrain’s economy is more diversified than Kuwait’s: the financial services sector contributes roughly 17% of GDP, making Manama one of the Gulf’s two dominant financial centres alongside Dubai. The country also has a more developed manufacturing base, including aluminium smelting, and has positioned itself as a regional hub for Islamic finance. This economic diversification is strategically significant because Bahrain has proportionally lower oil reserves than Kuwait or Saudi Arabia — the financial sector was, to some extent, a deliberate hedge against that exposure.

The BHD’s nominal strength is reinforced by Saudi Arabia’s implicit backstop role: the two countries share a causeway, a deep economic relationship, and a security alliance. Saudi Arabia’s vast financial resources have historically been seen as an informal guarantor of Bahraini monetary stability — a factor markets price into the risk premium attached to the dinar’s peg.

Investment angle: Bahrain’s status as a relatively open economy with few capital controls makes the BHD more accessible to international investors than most Gulf currencies. Its fintech regulatory sandbox and digital banking framework have drawn growing interest from global financial institutions in 2024–2025.

#1 — Kuwait: The Uncontested Crown

KWD/USD: ≈ 3.27 | Oil reserves: world’s 6th largest | Inflation: ~2.1% | FX reserves: > $45bn (CBK)

The Kuwaiti dinar is, by the most direct measure available — how many US dollars it takes to buy one unit — the strongest currency in the world. One dinar buys approximately $3.27 at current exchange rates, a premium that has been maintained, with only modest fluctuation, for decades.

Kuwait’s monetary position begins with geology. The country sits atop the world’s sixth-largest proven oil reserves, estimated at approximately 101 billion barrels — a figure that, relative to the country’s population of around 4.3 million citizens (and a total population of roughly 4.7 million including expatriates), represents extraordinary per-capita resource wealth. Oil and petroleum products account for more than 85% of government revenue and over 90% of export earnings. When oil prices are elevated — as they broadly have been across 2022–2025 — the fiscal arithmetic is essentially self-reinforcing.

The Central Bank of Kuwait manages the dinar through a managed peg to an undisclosed basket of international currencies, with the US dollar believed to constitute the largest single weight, given Kuwait’s oil revenues are denominated in dollars. This basket arrangement gives the CBK marginally more flexibility than a simple USD peg — it insulates the dinar slightly from bilateral dollar volatility.

Kuwait’s sovereign wealth fund, the Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA), is among the oldest and largest in the world, with assets variously estimated at over $900 billion. This vast stock of externally held financial wealth provides an additional buffer for the currency — in extremis, the KIA’s assets could theoretically be liquidated to defend the dinar. In practice, they have never needed to be. The combination of ongoing oil revenues, low domestic inflation (circa 2.1%), and conservative fiscal management has kept the dinar stable in nominal terms for as long as most investors can remember.

It is worth acknowledging the critique: Kuwait’s currency strength reflects resource rents and fiscal subsidies rather than diversified economic productivity. The dinar has not been “stress-tested” in the way the Swiss franc has, across multiple non-commodity-linked monetary regimes. A world permanently transitioning away from fossil fuels would eventually restructure the fiscal basis of KWD strength. But “eventually” is doing considerable work in that sentence. In March 2026, with global oil demand still running at near-record levels and the energy transition proceeding more slowly than many modelled, the Kuwaiti dinar remains — unchallenged — the most valuable currency on the planet by exchange rate.

Travel angle: For visitors holding stronger currencies (GBP, CHF, EUR), Kuwait is a genuinely affordable destination for what it offers — a sophisticated urban environment, world-class dining, and proximity to the rest of the Gulf. For those arriving with weaker currencies, the dinar’s strength can feel formidable at the exchange counter.

The Big Picture: What Strong Currencies Mean for Travel and Investment in 2026

The Travel Equation

Currency strength creates a purchasing-power asymmetry that sophisticated travellers have long exploited. Holding a strong currency — Kuwaiti dinar, British pound, Swiss franc, or euro — means that destinations with weaker currencies effectively go “on sale” from the holder’s perspective.

In 2026, the most compelling value gaps are between strong-currency nations and emerging markets where inflation has eroded local purchasing power without triggering proportionate currency depreciation. South-East Asia (Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia), parts of Central and Eastern Europe, and much of Sub-Saharan Africa offer exceptional experiential value for travellers from the currencies on this list.

For travellers from weaker-currency nations visiting strong-currency countries — the United Kingdom, Switzerland, or the Gulf states — the inverse applies. The exchange rate headwind is real and material. Budget accordingly.

The Investment Case

Strong currencies are not automatically superior investment vehicles. A currency that is strong because it is pegged to the dollar (BHD, OMR, JOD, KYD) offers exchange-rate stability but does not offer upside appreciation. The Swiss franc and Singapore dollar — both managed floats — have historically appreciated in real terms over time, making them genuine long-term stores of value.

The broader investment signal from strong-currency nations is less about the currency itself and more about the policy environment it implies: low inflation, institutional independence, disciplined fiscal management, and rule of law. These are also the conditions most conducive to long-term capital preservation and, frequently, to strong equity market performance.

The Geopolitical Dimension

Several currencies on this list are exposed to geopolitical tail risks that their stable exchange rates do not fully price. Gulf currencies depend on continued hydrocarbon demand and regional stability. The pound is permanently sensitive to UK fiscal credibility and any resurgence of concerns about debt sustainability. The euro faces structural tensions that have been managed but not resolved.

The Swiss franc and Singapore dollar stand apart: their strength is built on institutional foundations that are largely independent of any single commodity price, political decision, or regional dynamic. In a world of elevated geopolitical uncertainty, that institutional bedrock commands a premium that is likely to persist.

Conclusion: Currency Strength as a Mirror of National Character

The currencies at the top of this ranking are not accidents. The Kuwaiti dinar is strong because Kuwait made conservative choices about how to manage extraordinary resource wealth — choices that not every resource-rich nation has made. The Swiss franc is strong because Switzerland has maintained institutional discipline across a century and three-quarters of monetary history. The pound retains its position because British financial markets have earned global trust over decades, even while political decisions have periodically tested it.

For travellers, the lesson is straightforward: when your home currency is strong, the world effectively gives you a discount on its experiences. For investors, the lesson is more nuanced: strength by nominal exchange rate and strength by structural monetary credibility are not the same thing — and in the long run, the latter matters more.

In 2026, the world’s currency hierarchy reflects, as it always has, the aggregate of every monetary policy decision, every fiscal choice, and every institutional investment that preceded it. The dinar, the franc, the pound, the rial — each is a ledger of its nation’s choices, settled daily on the world’s foreign exchange markets.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ Schema)

Q1: What is the strongest currency in the world in 2026?

The Kuwaiti Dinar (KWD) is the strongest currency in the world in 2026 by nominal exchange rate, trading at approximately $3.27 per dinar as of early March 2026. Its strength is underpinned by Kuwait’s vast oil reserves, conservative central bank management, and a managed basket peg that maintains extraordinary stability.

Q2: Which country has the strongest currency for travel in 2026?

For travellers, holding UK Pounds Sterling (GBP), Swiss Francs (CHF), or Euros (EUR) provides the most practical travel purchasing power advantage globally, as these currencies are widely accepted worldwide and deliver significant exchange-rate advantages in emerging markets across Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe.

Q3: Why is the Kuwaiti Dinar so strong?

The Kuwaiti Dinar’s strength derives from Kuwait’s position as one of the world’s largest per-capita oil exporters, responsible fiscal management by the Central Bank of Kuwait, a managed currency peg to a basket of international currencies, low domestic inflation, and the backing of the Kuwait Investment Authority — one of the world’s largest sovereign wealth funds, with assets estimated at over $900 billion.

Q4: Is a strong currency good for a country’s economy?

A strong currency has both benefits and costs. Benefits include lower import costs (reducing inflation), greater purchasing power for citizens abroad, and stronger investor confidence. Costs include reduced export competitiveness, as locally produced goods become more expensive for foreign buyers, and potential pressure on manufacturing sectors. Countries like Switzerland and Singapore manage this tension deliberately through monetary policy.

Q5: What are the best currencies to hold as an investment in 2026?

For capital preservation, the Swiss Franc (CHF) and Singapore Dollar (SGD) have the strongest track records of long-term purchasing-power preservation among free-floating or managed-float currencies. For nominal stability, USD-pegged Gulf currencies (KWD, BHD, OMR) offer predictable exchange rates but limited upside appreciation. The US Dollar retains unparalleled liquidity and reserve-currency status. Diversification across multiple hard currencies remains the consensus recommendation from institutional investors.

Sources : Data sourced from Central Bank of Kuwait, Central Bank of Bahrain, Central Bank of Oman, Monetary Authority of Singapore, Swiss National Bank, Bank of England, European Central Bank, IMF World Economic Outlook (Oct 2025 / Jan 2026 update), World Bank International Comparison Programme, BIS Triennial Survey, Bloomberg FX data, and Reuters market data. Exchange rates are indicative mid-market values as of early March 2026 and are subject to market fluctuation.