Business

How Generational Wealth Transfer Will Reshape China’s Economy

In the hushed private banking suites of Hong Kong and Singapore, a seismic shift is underway. Family patriarchs who built empires from rubble in the decades following China’s economic reforms now face an inescapable reality: their heirs—globally educated, digitally native, and values-driven—are preparing to inherit the largest concentration of private wealth in human history. This transition will do more than shuffle assets between generations. It will fundamentally recalibrate how capital flows through the world’s second-largest economy, reshape consumption patterns from property to experiences, and accelerate an eastward tilt in global financial power that began quietly but now moves with tectonic force.

The generational wealth transfer in China represents far more than inheritance planning. It is the economic inflection point where demographic destiny meets accumulated prosperity, where women inheritors will command unprecedented financial influence, and where the fraying social contract around property wealth collides with the imperatives of a consumption-driven future. The implications span geopolitics, fiscal sustainability, market architecture, and the lived reality of hundreds of millions of Chinese families navigating the most rapid aging process any major economy has ever experienced.

The Scale: Beyond Previous Estimates

Global wealth transfer projections have escalated dramatically. Cerulli Associates estimates that $124 trillion will change hands worldwide by 2048, surpassing total global GDP. UBS’s Global Wealth Report 2025 refined these figures, projecting over $83 trillion in transfers over the next 20–25 years, with $74 trillion moving between generations and $9 trillion transferring laterally between spouses.

For China specifically, the numbers have evolved beyond the 2023 Hurun estimate of $11.8 trillion over 30 years. UBS now projects mainland China will see more than $5 trillion in intergenerational wealth movement over the next two decades—a figure likely conservative given China’s billionaire population expanded by over 380 individuals daily in 2024. When combined with Oliver Wyman’s estimate that $2.7 trillion will transfer across Asia-Pacific by 2030, with Global Chinese families representing a substantial portion, the true scale approaches $6–7 trillion for Greater China through 2030 alone.

This wealth concentration is staggering. China’s projected transfers approach 30–35% of its current nominal GDP, creating both opportunity and peril. The wealth is highly concentrated: research indicates the top 1% of Chinese households control approximately one-third of the nation’s private wealth, five times more than the bottom 50% combined. How this capital reallocates will determine whether China navigates its demographic transition with economic resilience or faces a corrosive wealth effect that deepens consumption malaise.

The Demographic Imperative: Aging at Unprecedented Speed

China is experiencing the most compressed aging trajectory of any major economy in modern history. United Nations and World Bank projections show the population aged 65 and above doubling from 172 million (12.0%) in 2020 to 366 million (26.0%) by 2050. Some forecasts push this to 30% or higher, approaching Japan’s current super-aged society status but at a far earlier stage of per capita income development.

The dependency mathematics are brutal. China’s old-age dependency ratio—the number of retirees per working-age adult—will surge from approximately 0.13 in 2015 to 0.47–0.50 by 2050, mirroring the United Kingdom’s current burden. By 2050, China will transition from eight workers per retiree today to just two, straining pension systems, healthcare infrastructure, and family support networks simultaneously.

Unlike Western economies that grew wealthy before aging, China confronts what analysts term “growing old before growing rich.” China’s 65+ population is projected to reach 437 million by 2051, representing 31% of the total population—the largest elderly cohort on Earth. This creates fiscal pressures demanding over 10 million annual pension claimants by current trajectories, even as the working-age population contracts by an estimated 125 million between 2020 and 2050.

The demographic crisis is no longer theoretical. China’s population declined by 2.08 million in 2023, with the death rate reaching its highest level since 1974. The total fertility rate collapsed to 1.09 in 2022, well below replacement. Life expectancy, meanwhile, climbed to 77.5 years and is expected to reach 80 by 2050, with women averaging 88 years. These twin forces—collapsing births and extended longevity—create the conditions for history’s largest intergenerational asset transfer within a society still building its social safety net.

Property’s Wealth Effect: From Cornerstone to Constraint

For two decades, residential property served as China’s primary wealth accumulation vehicle. Urban households hold 70% of their assets in real estate, making housing the foundation of middle-class prosperity. Between 2010 and 2020, property prices in China’s top 70 cities surged nearly 60%, minting millionaires and cementing the conviction that real estate only appreciates.

Since 2021, that narrative has shattered. Housing prices have declined year-over-year for over four years, falling 3.8% in 2025 with forecasts projecting a further 0.5% drop in 2026 before modest stabilization in 2027. The property downturn has erased trillions in perceived wealth. Developers from Evergrande to Country Garden to Vanke—once symbols of unstoppable growth—now face distressed debt restructuring. In 2025, real estate investment fell 14.7%, new home sales dropped 8%, and the sector’s inventory-to-sales ratio reached 27.4 months in major cities, nearly double the healthy market threshold.

The negative wealth effect is profound. Households feel poorer, save more, and consume less. Over the past five years, household bank deposits nearly doubled to 160 trillion yuan ($22 trillion) by mid-2025—a defensive posture reflecting shattered confidence. Retail sales growth stagnated to barely 1% year-over-year by late 2025, with consumption contributing an estimated 1.7 percentage points to GDP growth, down from historical averages above 3 percentage points.

This creates a paradox for wealth transfer. Older generations hold substantial real estate assets acquired at lower valuations, but declining prices mean the inherited property wealth will be less valuable than anticipated. Meanwhile, younger cohorts who cannot afford today’s prices despite declines face reduced intergenerational support, as parents’ wealth is trapped in illiquid, depreciating assets. The property crisis doesn’t just constrain consumption today—it diminishes the wealth being transferred tomorrow.

Women Inheritors: The Silent Revolution in Capital Control

Perhaps no dimension of China’s generational wealth transfer has received less attention—or carries more transformative potential—than the shift of assets to women. Globally, Bank of America research estimates that women will receive approximately 70% of the $124 trillion great wealth transfer, with $47 trillion going directly to younger female heirs and $54 trillion passing to surviving spouses (95% of whom are women, given women’s longer life expectancy).

In China, this dynamic is amplified by cultural evolution and longevity gaps. Chinese women now live an average of 6–8 years longer than men, meaning widows will control substantial assets for extended periods before passing them to children. UBS highlights that approximately $9 trillion globally will move “sideways” to female spouses before generational transfer, reshaping who controls family capital.

Yet Chinese women historically faced systematic disadvantages in asset accumulation. Research shows only 37.9% of Chinese women own housing property (including co-ownership), compared to 67.1% of men. Among married individuals, just 13.2% of women hold property titles solely, versus 51.7% of married men. Sons receive more intergenerational transfers for housing than daughters, perpetuating gender wealth gaps.

The wealth transfer presents an opportunity to rebalance these inequities. Evidence from Next Generation wealth studies in Asia suggests younger Asian female inheritors prioritize impact investing, ESG-focused allocations, and portfolio diversification away from real estate toward equities and alternatives at higher rates than male counterparts or previous generations. Female wealth management clients demonstrate less emotional volatility, greater research diligence, and longer holding periods—traits that could channel inherited capital toward productive investment rather than speculative churning.

If Chinese women gain majority control over family wealth through inheritance and survivorship, investment patterns will shift toward healthcare, education, sustainability, and consumer services—sectors aligned with longer-term value creation. This contrasts with the property-speculation and heavy-industry bias that characterized first-generation male wealth builders. The gender dimension of China’s wealth transfer may prove as economically consequential as the generational one.

Fiscal Pressures and the Pension Crisis

China’s implicit social contract is fraying. For decades, families bore primary responsibility for elderly care, supported by high savings rates and multigenerational households. That model is collapsing. The one-child policy (1979–2015) means today’s elderly have five to six surviving children on average, but younger cohorts born in the late 1950s–1960s have fewer than two children. By 2050, many elderly will lack familial caregivers entirely.

Pension coverage remains incomplete. While urban workers enjoy basic pension schemes, rural residents and informal workers face gaps. The system runs deficits in multiple provinces, requiring central government transfers. As the dependency ratio surges, pension obligations will consume escalating shares of government budgets. Projections suggest pension liabilities could reach 53% of the population by 2050, an unsustainable burden without reform.

Healthcare costs compound the problem. China has 10 million citizens with Alzheimer’s and related dementias, a figure expected to approach 40 million by 2050. The prevalence of chronic diseases—cardiovascular conditions, cancer, diabetes—is rising as the population ages. An estimated 108–136 million Chinese lived with disabilities in 2020, projected to exceed 170 million by 2030, with over 70% being elderly by 2050.

The wealth transfer intersects these fiscal pressures in two ways. First, if inherited wealth enables families to self-fund elderly care, it reduces state burdens. Second, taxation of wealth transfers could provide revenue for social programs—though China currently levies no inheritance or gift taxes. The policy choice looms: allow dynastic wealth accumulation, or implement progressive transfer taxation to fund public services. Either path reshapes economic outcomes profoundly.

Investment Reallocation: From Concrete to Innovation

The property crisis is forcing a capital reallocation that the wealth transfer will accelerate. With real estate no longer a reliable store of value, Chinese households are diversifying. Despite the downturn, household savings of 160 trillion yuan provide fuel for new investment. Currently, only 5% of household wealth is allocated to equities, compared to 60% in real estate—leaving vast room for portfolio rebalancing.

Government policy encourages this shift. China’s onshore bond issuance grew from $17.2 trillion in 2020 to $24.1 trillion in 2024, absorbing domestic savings to fund R&D (up 8.9% year-over-year in 2024) and industrial subsidies. Retail investors drive 90% of stock market trades, and AI-led optimism fueled equity market rallies in 2025, redirecting household capital toward technology and innovation.

Next-generation inheritors amplify this trend. Surveys show 61% of Millennial and Gen Z high-net-worth individuals are willing to invest in high-growth niche markets, including private equity, cryptocurrencies, and alternative assets. By January 2025, Asian HNWIs held 15% of portfolios in alternatives—substantially higher than previous generations. Young Chinese inheritors prioritize digital efficiency, exclusive investments, and ESG impact, not legacy real estate empires.

This reallocation matters geopolitically. If Chinese capital flows toward domestic innovation, green technology, and healthcare rather than overseas property or dollar-denominated assets, it reinforces economic self-reliance and the “dual circulation” strategy. Conversely, if wealthy families diversify offshore—through Hong Kong family offices, Singapore trusts, or Western equities—it represents capital flight that undermines Beijing’s policy objectives.

Geopolitical Implications: The Eastward Tilt Accelerates

China’s wealth transfer does not occur in isolation. It coincides with a broader shift in global wealth concentration. UBS reports that the US and China jointly account for over half of all personal wealth globally. In 2024, China added more than 380 new millionaires daily, trailing only the US (~1,000 daily). By 2029, UBS projects 5.34 million new dollar millionaires globally, with the majority concentrated in the US and China.

Asia-Pacific’s share of global private wealth climbed from 6% in 2000 to 21% today, with projections reaching 25% by 2029 ($99 trillion). Within Asia, China remains the anchor. Hong Kong and Singapore have emerged as wealth management hubs, with 80% of capital inflows originating within Asia, signaling the region is no longer merely participating in global finance—it is driving it.

The geopolitical implications are stark. As Chinese capital remains concentrated in Asia, Western financial institutions lose influence. Dollar hegemony faces subtle erosion as Asian wealth managers, family offices, and UHNW individuals transact increasingly in yuan, Hong Kong dollars, and regional currencies. Trade flows follow capital flows: wealthy Asian inheritors invest in regional supply chains, technology ecosystems, and consumption markets, accelerating economic integration independent of Western-led globalization.

The wealth transfer also intersects US-China strategic competition. Technology transfers, intellectual property, and corporate control hinge on who owns equity stakes. If Chinese inheritors diversify into Western tech, real estate, and infrastructure, it raises national security concerns. Conversely, if Western investors are excluded from Chinese family enterprises during succession, it fragments global markets. The great wealth transfer is not merely economic—it is a contest for future geopolitical leverage.

The Next Generation: Values, Governance, and Succession Challenges

Family business research reveals deep generational contrasts in Asia. First-generation Chinese entrepreneurs—often China-based, control-oriented, and legacy-focused—built fortunes through relentless execution in manufacturing, real estate, and export industries. Their successors, by contrast, are globally educated, culturally agile, and drawn to impact investing, philanthropy, and flexible governance.

The succession gap is real. Asia Generational Wealth Report 2025 found 72% of founders see children as likely successors, yet 24% believe successors are underprepared. Diverging aspirations complicate transitions: NextGen prioritizes starting ventures and social impact over preserving family businesses. Without careful governance, succession failures could destroy enterprise value, disrupt employment, and fragment wealth.

China’s legal infrastructure for wealth transfer remains underdeveloped. The country has no inheritance or gift taxes, creating planning uncertainty if such levies are introduced. Family trusts, once rare, are expanding but face regulatory ambiguity. In 2025, Shanghai and Beijing introduced real estate trust registrations, allowing property transfers into trusts for estate planning—a breakthrough, but one limited to pilot cities.

Successful wealth transfers require not just legal structures but also family communication. Yet research shows fewer than 25% of families globally discuss succession openly, and over 38% of women avoid these conversations entirely. In China, where filial piety and hierarchy traditionally govern family dynamics, frank discussions about mortality, asset division, and successor capability remain culturally fraught. The result: avoidable disputes, suboptimal succession, and value destruction.

Market Implications: Consumption, Credit, and Growth

China’s wealth transfer will shape macroeconomic trajectories through consumption, credit demand, and investment priorities. If inherited wealth boosts household confidence, consumption could recover from its current doldrums. Morgan Stanley economists argue that halting property market declines is “crucial to mitigate the negative wealth effect on household consumption,” and that “restoring confidence in this key asset class will be instrumental in unlocking spending power across the economy.”

Yet the timing is uncertain. Even if property prices stabilize in late 2026 or 2027, consumer sentiment recovers slowly. Many households prioritize debt repayment and savings over consumption. Younger buyers face job insecurity and modest income growth, opting for rentals over purchases. Demand remains reasonably strong among first-time buyers and families seeking school-district housing, but large-scale investment appetite for new residential construction is subdued.

The credit channel also matters. If wealth transfers enable heirs to pay down debt, household leverage declines, strengthening balance sheets but reducing credit-fueled growth. Alternatively, if heirs borrow against inherited assets to fund consumption or investment, it extends the credit cycle. China’s household bad loan ratio reached 1.33% in the first half of 2025, exceeding the corporate ratio for the first time—a warning signal amid ongoing property and labor market pressures.

For policymakers, the wealth transfer represents both opportunity and risk. If managed well—through inheritance taxation that funds social programs, governance frameworks that enable smooth succession, and policies encouraging productive investment—it could support sustainable growth. If mismanaged—allowing dynastic concentration, capital flight, or succession disputes—it exacerbates inequality, undermines social cohesion, and slows economic dynamism.

Conclusion: A Crossroads for China’s Economic Future

China’s generational wealth transfer is not merely a demographic footnote. It is the economic event that will define the next two decades. The confluence of the world’s largest elderly population, the fastest aging process any major economy has experienced, and the most compressed wealth accumulation in modern history creates conditions without historical precedent.

The outcomes are not predetermined. If property markets stabilize and inherited wealth channels toward consumption, China could sustain 4–5% GDP growth through the 2030s, navigating the middle-income trap. If women inheritors allocate capital toward innovation, sustainability, and services, China’s economic structure diversifies beyond manufacturing and real estate. If family businesses transition smoothly to prepared successors, enterprise value compounds across generations, supporting employment and tax revenues.

Conversely, if property wealth evaporates, consumption stagnates, and fiscal burdens overwhelm government capacity, China risks Japan-style secular stagnation—or worse, given its earlier stage of development. If dynastic wealth concentrates without redistribution, inequality ignites social tensions. If capital flees offshore, Beijing’s policy autonomy erodes.

For global markets, the implications are profound. The shift of trillions in private wealth from aging entrepreneurs to younger, female, globally integrated inheritors will reshape capital flows, trade patterns, and geopolitical alignments. The eastward tilt of economic power, already underway, will accelerate. Investors, policymakers, and strategists who understand this transition will position themselves for the opportunities it creates. Those who ignore it will be blindsided.

China is at a crossroads. The great wealth transfer will determine which path it takes…..

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

Jazz Wins 190 MHz in Pakistan’s Historic 5G Auction – Triples Spectrum to 284.4 MHz for $239M

In a single, decisive afternoon that will be marked as a pivotal moment in Pakistan’s economic history, the nation has finally and forcefully entered the global 5G arena. The country’s long-anticipated 5G spectrum auction concluded today, March 10, 2026, raising a staggering $507 million for the national exchequer in a matter of hours.

Emerging as the undisputed heavyweight champion from this digital contest is Jazz, the nation’s largest mobile operator. Backed by its parent company, VEON, Jazz has committed $239.375 million to secure a massive 190 MHz block of new spectrum, a move that more than triples its total holdings and redraws the competitive map of South Asia’s telecommunications landscape. This wasn’t merely a business transaction; it was a declaration of intent, positioning Jazz—and by extension, Pakistan—to leapfrog years of digital latency and begin closing the profound connectivity gap that has long hampered its immense potential.

The results of the Pakistan 5G spectrum auction 2026 signal a tectonic shift. For a nation where nearly 40% of the population still lacks basic 4G access and per-user data consumption hovers at a modest 8 GB per month—well below the regional average of 20 GB—this auction is the starting gun for a digital revolution. Jazz’s aggressive acquisition, particularly its strategic capture of the coveted 700 MHz band, is a clear bet on a future where high-speed internet is not a luxury for the urban elite, but a utility for the masses, from the bustling markets of Karachi to the remote valleys of Gilgit-Baltistan. As the dust settles, the implications are clear: Pakistan’s digital future, for better or worse, will be largely shaped by the success of this monumental investment.

Breaking Down the Auction: Jazz Emerges Victorious

The auction, managed with notable transparency by the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA), was a swift and high-stakes affair. Of the 480 MHz of spectrum sold, the Jazz spectrum auction result was a clear victory. The company secured the largest and most diverse portfolio of frequencies, a strategic haul designed for both capacity and coverage.

The specifics of the Jazz 190 MHz Pakistan acquisition paint a detailed picture of its ambitions:

- 50 MHz in the 3500 MHz band: This is the prime global frequency for 5G, offering immense capacity and blazing-fast speeds. It will form the backbone of Jazz’s initial 5G rollout in dense urban centers like Lahore, Islamabad, and Karachi, where data demand is highest.

- 70 MHz in the 2600 MHz band: A crucial capacity layer that complements the 3500 MHz band, this spectrum will handle heavy data traffic and ensure a consistent, high-quality user experience as the 5G network matures.

- 50 MHz in the 2300 MHz band: Another vital capacity band, which provides a solid foundation for expanding 4G services and managing the transition to 5G.

- 20 MHz in the 700 MHz band: Perhaps the most strategically critical piece of the puzzle, this low-band spectrum is the key to unlocking the rural market.

This combination of low, mid, and high-band spectrum gives Jazz an unparalleled toolkit to execute a multi-layered network strategy, a sophisticated approach more akin to operators in developed markets than what is typical in the region.

From 94.4 MHz to 284.4 MHz: What Tripling Spectrum Really Means

For the layman, spectrum can be an abstract concept. In reality, it is the invisible real estate upon which all wireless communication is built. Before the auction, Jazz operated on a constrained 94.4 MHz of spectrum. This limited its ability to handle the exponential growth in data demand, leading to network congestion and a ceiling on potential service quality.

The headline, “Jazz triples spectrum holdings to 284.4 MHz,” barely does justice to the operational transformation this enables. It’s the difference between a two-lane country road and a six-lane superhighway. This dramatic expansion provides three immediate benefits:

- Massive Capacity Boost: The new frequencies, particularly in the mid-bands (2300 MHz, 2600 MHz, 3500 MHz), will immediately alleviate congestion on the existing 4G network. This means faster, more reliable speeds for millions of current users, even before a single 5G tower is activated.

- A Credible Path to 5G: True 5G requires wide, contiguous blocks of spectrum to deliver its promised gigabit speeds and ultra-low latency. With 50 MHz in the 3500 MHz band, Jazz now has the foundational asset to launch a world-class 5G service, enabling next-generation applications from the Internet of Things (IoT) to cloud gaming and smart cities.

- Future-Proofing the Network: By securing such a vast portfolio, Jazz has ensured it has the resources to meet Pakistan’s data demands for the next decade. It avoids the piecemeal, incremental upgrades that have plagued many emerging markets, allowing for long-term, strategic network planning.

The 700 MHz Prize: Game-Changer for Rural Pakistan

While the high-band spectrum grabs headlines for its speed, the quiet hero of this auction is the Jazz 700 MHz band Pakistan rural coverage plan. Low-band spectrum like 700 MHz possesses superior propagation characteristics, meaning its signals travel much farther and penetrate buildings more effectively than high-band signals.

This is a game-changer for a country with Pakistan’s geography and demographics. Building a network in sparsely populated or mountainous regions with traditional high-frequency spectrum is often economically unviable, requiring a dense grid of towers. The 700 MHz spectrum rural connectivity Pakistan strategy allows Jazz to cover vast swathes of the countryside with a fraction of the infrastructure.

This single allocation is the most concrete step taken to date to bridge Pakistan’s stubborn digital divide. It holds the promise of bringing reliable, high-speed mobile broadband to millions of citizens for the first time, unlocking access to education, e-health, digital finance, and modern agricultural practices. This directly addresses one of the most significant hurdles to inclusive economic growth. As Aamir Ibrahim, CEO of Jazz, noted, this investment is about “more than just 5G in cities; it’s about building a digital ecosystem that includes every Pakistani.” This sentiment, backed by the physics of the 700 MHz band, now carries the weight of genuine possibility.

Competitor Landscape: How Zong and Ufone Fared

While Jazz was the clear winner, it was not the only player. The Pakistan 5G auction results show a broader commitment to the country’s digital future from other key operators.

| Operator | Total Spectrum Won | Key Bands Acquired (MHz) | Total Outlay (Approx.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jazz | 190 MHz | 3500, 2600, 2300, 700 | $239.375 M |

| Ufone | 180 MHz | 3500, 2600, 2300 | $198 M |

| Zong | 110 MHz | 3500, 2600 | $69 M |

The Jazz vs Zong vs Ufone 5G spectrum allocation reveals distinct strategies. Ufone also made a significant play, securing a large 180 MHz block to bolster its position and compete aggressively in the 5G race. Zong, a subsidiary of China Mobile and an early pioneer of 4G in Pakistan, took a more modest 110 MHz, likely focusing its resources on upgrading its existing, robust network infrastructure for 5G services in its urban strongholds. The competitive dynamic is now set for a fierce three-way race, which will ultimately benefit consumers with better services and more competitive pricing.

Economic Ripple Effects: Closing the Digital Divide

The Pakistan 5G auction economic impact 2026 cannot be overstated. Beyond the immediate $507 million windfall for the government, the true value lies in the long-term multiplier effect on the economy. The Jazz $1 billion investment 5G Pakistan commitment, announced in conjunction with the auction, is a powerful vote of confidence in the country’s policy direction and economic stability.

This capital expenditure will flow into network hardware, local engineering talent, and civil works, creating thousands of jobs. More profoundly, the resulting digital infrastructure will serve as a platform for innovation across every sector. For a country with a youthful, entrepreneurial population, access to reliable, high-speed connectivity is the critical missing ingredient. It will catalyze the growth of the gig economy, e-commerce, fintech, and a burgeoning startup scene that has, until now, been constrained by digital scarcity. This is the macro-level story that international investors and bodies like the IMF will be watching closely.

Policy Verdict: A Win for Transparent Spectrum Management

Finally, the execution of the auction itself is a significant victory. In a region where spectrum allocation has often been a contentious and opaque process, the PTA has delivered a model of efficiency and transparency. Unlike the delayed and complex processes seen in neighboring India or Bangladesh, Pakistan’s ability to conduct a clean, multi-band auction in a single day sets a new regional benchmark. It sends a powerful signal to the global investment community that Pakistan is a serious and reliable destination for foreign direct investment in the technology sector. This successful policy execution, as detailed in reports by outlets like Dawn and Business Recorder, builds crucial sovereign credibility.

The road ahead is not without its challenges. Rolling out a nationwide 5G network while simultaneously expanding 4G to underserved areas is a monumental undertaking. It will require navigating complex regulatory hurdles, securing the supply chain for advanced equipment, and managing the significant debt load associated with such a large investment. However, as of today, the path is clear. With its newly tripled spectrum holdings and a clear strategic vision, as outlined in the official VEON announcement, Jazz has not just won an auction; it has accepted the mantle of leadership in powering Pakistan’s digital destiny. The nation, and the world, is watching.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

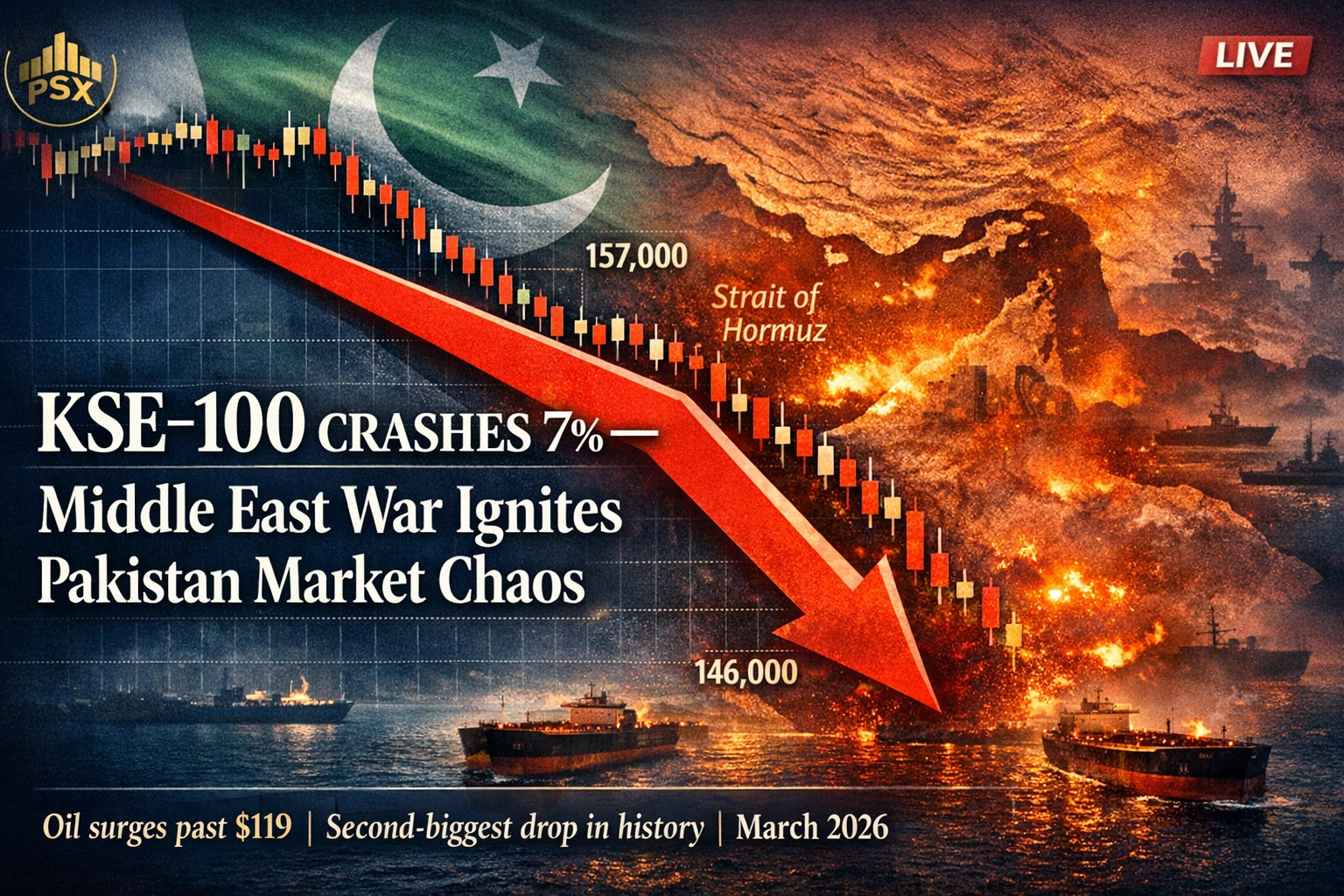

KSE-100 Plunges Nearly 7% Amid Escalating Middle East Tensions: What It Means for Pakistan’s Economy

The digital clock on Mr. Ahmed’s trading terminal in Karachi’s bustling financial district had barely clicked past 9:15 AM when the screen turned a ghastly red, reflecting the collective dread that swept through the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX). His life savings, meticulously built over decades of cautious investment, seemed to evaporate with each precipitous drop in the KSE-100 Index.

“It’s not just numbers on a screen,” he’d often tell his children, “it’s the future of our family, the cost of our education, the roof over our heads.” Today, that future felt acutely fragile. The morning’s aggressive sell-off wasn’t merely a market correction; it was a visceral reaction to geopolitical tremors reverberating from distant shores, a stark reminder of Pakistan’s deep integration into a volatile global economy.

Why KSE-100 Fell Today: A Cascade of Geopolitical Risk

Monday, March 9, 2026, will be etched into the annals of Pakistan’s financial history as a day of profound market distress. The KSE-100 Index settled at 146,480.14, marking a stunning 11,015.96 points (or 6.99%) decline. This devastating fall, the second-highest single-day percentage drop in the index’s history, sent shockwaves across the nation’s financial landscape.

The day began with an immediate and aggressive sell-off, shedding 9,780.15 points (6.21%) by 9:22 AM. This dramatic freefall triggered a full market halt, as per PSX rules for circuit breakers, with the KSE-30 Index down 5%. Trading resumed precisely an hour later, at 10:22 AM, yet any hopes of a substantial recovery were dashed. A limited midday rebound gave way to a largely sideways and uncertain afternoon, as investors grappled with the unfolding global narrative.

The primary catalyst for this precipitous decline was unmistakably clear: escalating tensions in the Middle East. The deepening U.S.-Israeli conflict with Iran has unleashed a wave of uncertainty across global markets, but its impact is acutely felt in economies like Pakistan, highly dependent on imported energy. The immediate and most alarming fallout has been in the oil markets, with prices surging by an astounding ∼20% to multi-year highs, now exceeding $119 per barrel. Fears of disruption to the vital Strait of Hormuz, through which a significant portion of the world’s oil transits, have ignited a scramble for energy security and sent commodity markets into disarray [reuters_oil_surge_analysis].

A Troubling Precedent: KSE-100 Single-Day Decline 2026

The severity of today’s market performance is amplified by its historical context. Topline Securities research highlights a deeply concerning trend: the three largest single-day declines in the KSE-100’s history have all occurred in 2026. This alarming statistic suggests not merely a temporary blip, but potentially a new, more volatile paradigm for Pakistan’s equity markets, underscoring the fragility inherent in its economic structure in the face of external shocks.

Historically, Pakistan’s markets have shown resilience, navigating political upheavals, economic crises, and regional conflicts. However, the confluence of persistent domestic vulnerabilities — including perennial balance of payments issues, high public debt, and inflationary pressures — with intensified global geopolitical instability is creating a perfect storm. The market’s reaction today is a testament to the fact that while local factors are always at play, the sheer force of global events can swiftly overshadow them, particularly when they impinge on fundamental economic costs like energy.

Macroeconomic Fallout: Impact of Iran Conflict on Pakistan Stock Market

The implications of the surging oil prices and the wider Middle East conflict for Pakistan’s economy are profound and multifaceted.

- Inflationary Spiral: Pakistan is a net oil importer, making its economy highly vulnerable to global energy price shocks. A sustained increase in oil prices to over $119/barrel will inevitably translate into higher domestic fuel and power costs. This will directly feed into an already elevated inflation rate, eroding purchasing power and potentially triggering social unrest. The State Bank of Pakistan will face immense pressure to maintain tight monetary policy, further stifling economic growth [bloomberg_energy_crisis_inflation_shock].

- Rupee Depreciation & Balance of Payments Crisis: Higher oil import bills will place an unbearable strain on Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves. This intensified demand for dollars to finance imports will inevitably lead to further depreciation of the Pakistani Rupee. A weaker rupee makes all imports more expensive, fueling a vicious cycle of inflation and exacerbating the balance of payments deficit. The central bank’s ability to defend the currency will be severely tested.

- IMF Programme Jeopardised: Pakistan is currently engaged in a critical International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme, which often hinges on fiscal discipline and external account stability. The unforeseen surge in oil prices could derail key macroeconomic targets, jeopardizing tranche disbursements and potentially leading to renegotiations or even suspension of the programme. This would send a catastrophic signal to international lenders and investors, further tightening access to much-needed external financing.

- FDI Flight and Investor Confidence: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), always a sensitive indicator, is likely to pull back significantly. Global investors perceive Pakistan as an emerging market with inherent risks; escalating regional conflict and economic instability dramatically heighten that risk premium. The why KSE-100 fell today Middle East Iran war narrative sends a clear message of heightened risk, prompting a flight to safer assets and reducing the appetite for frontier market exposure.

- Energy Cost & Industrial Output: For Pakistan’s manufacturing and industrial sectors, higher energy costs mean reduced competitiveness and increased operational expenses. This could lead to factory closures, job losses, and a slowdown in economic activity, further dampening prospects for growth and poverty alleviation.

Global Echoes & Investor Lessons: Lessons from Past Crises

The current geopolitical and energy shock, while unique in its specifics, echoes past crises that have tested the resilience of emerging markets. Comparisons might be drawn to the oil shocks of the 1970s or the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s, where external vulnerabilities coupled with internal imbalances created systemic risks. Bloomberg’s analysis of the Iran conflict’s impact on emerging markets [bloomberg_emerging_markets_fallout] highlights the fragility of recovery narratives when confronted with such potent external forces.

For international investors, today’s PSX trading suspended oil price surge 2026 event serves as a sharp reminder of the importance of geopolitical risk assessment, especially in regions with high energy import dependence and pre-existing economic fragilities. Diversification, hedging strategies, and a keen eye on global macro trends become not just advisable, but imperative. The KSE-100, once hailed for its potential, now stands as a cautionary tale of how quickly sentiment can turn amidst global uncertainty.

Outlook: Will Markets Stabilise?

The immediate outlook for the Pakistan Stock Exchange decline remains precarious. While the initial shock of the largest single-day falls KSE-100 history event has been absorbed, sustained market stability will depend on several critical factors:

- De-escalation in the Middle East: Any diplomatic breakthroughs or de-escalation of military tensions would provide immediate relief to oil markets and, by extension, to Pakistan’s economy. However, the current trajectory suggests a prolonged period of uncertainty.

- Global Oil Price Trajectory: If oil prices consolidate at or above $119/barrel, the economic headwinds for Pakistan will persist and intensify. A significant pullback in crude prices would offer a much-needed reprieve.

- Policy Response: The Government of Pakistan and the State Bank will need to demonstrate swift and decisive policy responses. This includes robust fiscal management to mitigate inflationary pressures, strategic foreign exchange interventions (if feasible), and clear communication with the public and international stakeholders to restore confidence. Austerity measures, however unpopular, may become unavoidable.

- International Support: The role of international financial institutions and friendly nations will be crucial. Access to emergency financing or favourable credit lines could provide a much-needed buffer against external shocks and prevent a full-blown financial crisis.

Conclusion: Navigating the Storm with Measured Hope

Today’s dramatic events on the Pakistan Stock Exchange are more than just a blip on the radar; they are a stark reflection of the interconnectedness of global finance and geopolitics. The KSE-100’s near 7% plunge underscores Pakistan’s acute vulnerability to external shocks, particularly when domestic economic fundamentals remain challenging.

For investors, both local and international, prudence is paramount. For policymakers, the path ahead demands decisive action, strategic foresight, and unwavering commitment to economic stability. While the immediate future appears fraught with challenges, Pakistan has a history of resilience. With judicious policy-making, transparent communication, and timely international support, the nation can hope to navigate these tempestuous waters. The human stories, like Mr. Ahmed’s, remind us that behind every market statistic lies real livelihoods, real aspirations, and a profound hope for a more stable tomorrow.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Opinion

Boeing’s 500-Jet China Deal: Trump-Xi Summit’s $50B Game-Changer

On a Friday afternoon in early March, Boeing’s stock did something it hadn’t done in months: it surged. Shares of the aerospace giant jumped as much as 4 percent — the best performance on the Dow Jones Industrial Average that day — after Bloomberg reported that the company is closing in on one of the largest aircraft sales in its 109-year history. The prize: a 500-aircraft order for 737 Max jets from China, to be unveiled when President Donald Trump makes his first state visit to Beijing since 2017 — scheduled for March 31 to April 2.

If confirmed, the deal would represent nothing less than Boeing’s formal re-entry into the world’s second-largest aviation market after years of diplomatic cold-shouldering, safety-related groundings, and trade-war turbulence. It would also cement a pattern that has quietly defined Trump’s second term: the systematic use of America’s largest exporter as a diplomatic sweetener in geopolitical negotiations.

The Numbers Behind the Boeing 737 Max China Deal

Let’s be precise about what is reportedly on the table. According to people familiar with the negotiations cited by Bloomberg, the headline figure is 500 Boeing 737 Max jets — narrowbody, single-aisle workhorses that form the backbone of Chinese domestic aviation. Separately, the two sides are in advanced discussions over a widebody package of approximately 100 Boeing 787 Dreamliners and 777X jets, though that portion of the deal is expected to be announced at a later date and would not feature in the Trump-Xi summit communiqué.

At current list prices — the 737 Max 8 carries a sticker price of roughly $101 million per aircraft — the narrowbody package alone would approach $50 billion in nominal terms before the standard deep discounts that large airline orders attract. Factor in the widebody tranche, and the full package could eventually represent the single largest bilateral aviation deal ever struck between the United States and China.

Boeing itself declined to comment. China’s Ministry of Commerce did not respond to requests outside regular hours. The White House offered no immediate statement. But the market spoke clearly enough.

A Decade of Order Drought — and Why China Needs Boeing Now

To appreciate the magnitude of this potential agreement, consider the context. China once made up roughly 25 percent of Boeing’s order book. Today, Boeing holds only 133 confirmed orders from Chinese airlines — approximately 2 percent of its total book. Investing.com That collapse in Chinese demand was not accidental. It was the deliberate consequence of a cascade of crises: the global grounding of the 737 Max following two fatal crashes in 2018 and 2019, the trade tensions of Trump’s first term, and the pandemic-era freeze on civil aviation procurement.

Yet Chinese airlines have been quietly suffocating under constrained fleet capacity. Aviation analysts and industry sources say China needs at least 1,000 imported planes to maintain growth and replace older aircraft. WKZO The country’s carriers — Air China, China Eastern, China Southern — are operating aging fleets while passenger demand has rebounded sharply. The arithmetic of Chinese aviation is unforgiving: a country of 1.4 billion people, a rapidly expanding middle class, and a domestic network that still relies heavily on Western-certified jet technology cannot simply wait indefinitely for political stars to align.

Beijing has also been hedging. China is simultaneously in talks for another 500-jet order with Airbus that would be in addition to any Boeing deal — negotiations that have been in on-off discussions since at least 2024. WKZO But Airbus has its own capacity constraints and delivery backlogs. The reality is that both European and American planemakers are needed to feed China’s aviation appetite, which gives Boeing considerable strategic leverage — if it can navigate the politics.

Trump’s Boeing Diplomacy: A Playbook Refined

There is a recognizable pattern here, and it is worth naming explicitly. Trump has used Boeing as a tool to sweeten accords with other governments Yahoo Finance, and the China deal fits squarely within that framework. Earlier in his second term, large Boeing orders from Gulf carriers and Southeast Asian airlines followed Trump diplomatic visits — deals that generated political headlines and tangible employment commitments in American manufacturing states.

The Beijing summit, however, would be the most significant deployment of this strategy yet. US-China trade tensions have been acute in early 2026. Trump threatened to impose export controls on Boeing plane parts in Washington’s response to Chinese export limits on rare earth minerals. Yahoo Finance During earlier trade clashes, Beijing ordered Chinese airlines to temporarily stop taking deliveries of new Boeing jets — before resuming later that spring. WKZO

That on-off pattern illustrates the extraordinary vulnerability of commercial aviation to geopolitical temperature. Unlike soybeans or semiconductors, a Boeing 737 Max is not a fungible commodity. It requires years of certified maintenance infrastructure, pilot training, and regulatory framework built around American aviation standards. Both sides know this, which is precisely why aircraft orders have become such potent bargaining chips.

The planned summit structure — Trump in Beijing from March 31 to April 2, followed by Xi visiting Washington later in the year — also suggests a two-stage negotiation architecture. The 737 Max order would serve as a confidence-building gesture at the first meeting; the widebody 787 and 777X tranche would follow as trust is consolidated.

Boeing’s Recovery Trajectory: Why Timing Matters

For Boeing CEO Kelly Ortberg, the timing of a China breakthrough could scarcely be more critical. Boeing’s total company backlog grew to a record $682 billion in 2025, primarily reflecting 1,173 commercial aircraft net orders for the year, with all three segments at record levels. Boeing Yet the Chinese market has remained conspicuously absent from that recovery story.

Boeing has achieved FAA approval to increase 737 Max production to 42 jets per month, a significant step toward restoring manufacturing capacity, and the company plans to raise 787 Dreamliner output to 10 aircraft per month during 2026. Investing.com In short, for the first time in several years, Boeing actually has the industrial capacity to absorb a massive new order. Management has targeted approximately 500 737 deliveries in 2026 and 787 deliveries of roughly 90–100 aircraft, while targeting positive free cash flow of $1–3 billion for the year. TipRanks

A confirmed China order of this scale would not merely boost the backlog — it would validate the entire recovery narrative. It would signal to Wall Street that the 737 Max safety rebound is complete, that Chinese regulators have definitively recertified the aircraft, and that geopolitical risk has sufficiently receded to justify multi-year procurement commitments. As Reuters reported, Boeing’s share price rose 3.7 percent on the news — but analysts caution that several sticking points remain unresolved, and a deal is not yet assured.

Aviation Ripple Effects: What a China Mega-Deal Means for Global Travelers

The significance of a Boeing 737 Max China order in 2026 extends well beyond corporate balance sheets. Chinese carriers operating newer, more fuel-efficient 737 Max jets would dramatically expand route networks — both domestically and internationally. The 737 Max 10, capable of flying roughly 3,300 nautical miles at maximum range, opens trans-regional routes that older Chinese narrowbody fleets cannot economically serve.

For the global travel industry — and for the Expedia-era traveler booking multi-stop itineraries across Asia — this translates into more competitive airfares, denser flight schedules out of Chinese hub airports, and expanded connectivity between Chinese secondary cities and international destinations. Tourism economists estimate that each percentage point increase in seat capacity on a major international corridor correlates with a 0.6 to 0.8 percent increase in inbound tourist arrivals. A Chinese aviation expansion of this magnitude, fuelled by 500 new-generation jets, would register meaningfully in global travel demand forecasts through the late 2020s.

The geopolitical calculus cuts the other way too. Should talks collapse — perhaps due to escalation over Taiwan, renewed rare-earth export controls, or a postponement of the Trump visit, which Bloomberg noted could occur if the ongoing US-Iran situation deteriorates — Boeing’s China exposure remains an open wound rather than a healed scar.

Historical Context: The Ghosts of Boeing-China Deals Past

This would not be the first time a US presidential visit to China generated a headline Boeing order. In 2015, during Barack Obama’s final engagement with Xi Jinping, Chinese carriers placed orders for over 300 Boeing jets — a deal that at the time was celebrated as a pillar of the bilateral commercial relationship. It took less than four years for that relationship to unravel under the dual pressures of the MAX crisis and Trump’s first-term tariffs.

The lesson is not that such deals are illusory. It is that they are fragile by design — deeply dependent on the political weather. A Boeing 500-plane order tied to Trump’s Beijing summit is, in that sense, simultaneously a genuine commercial transaction and a diplomatic performance. Its durability will depend less on what is signed in Beijing in April than on what is negotiated, month by month, in the trade relationship that follows.

Forward Outlook: Promise, Risk, and the Long Game

Boeing’s aircraft stand to feature prominently in whatever trade framework emerges from the Trump-Xi summit. But seasoned observers of US-China commercial aviation will note that a similar mega-deal euphoria surrounded Airbus last year — and ultimately failed to materialize. Given the fraught geopolitical backdrop, Boeing’s order bonanza is not assured, and two people familiar with the talks have specifically cautioned that deal completion remains uncertain. Yahoo Finance

What is certain is this: the structural demand is real, the production capacity is finally in place, and the political incentive on both sides has rarely been stronger. For Boeing, recapturing even a fraction of what was once a market that constituted a quarter of its order book would represent a transformation of its strategic position. For China’s airlines, new Boeing jets mean competitive fleets, lower operating costs, and the capacity to serve a travelling public that has never stopped wanting to fly.

The planes, as ever, are ready. The question is whether the politics will let them take off.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

-

Markets & Finance2 months ago

Markets & Finance2 months agoTop 15 Stocks for Investment in 2026 in PSX: Your Complete Guide to Pakistan’s Best Investment Opportunities

-

Analysis1 month ago

Analysis1 month agoBrazil’s Rare Earth Race: US, EU, and China Compete for Critical Minerals as Tensions Rise

-

Banks2 months ago

Banks2 months agoBest Investments in Pakistan 2026: Top 10 Low-Price Shares and Long-Term Picks for the PSX

-

Investment2 months ago

Investment2 months agoTop 10 Mutual Fund Managers in Pakistan for Investment in 2026: A Comprehensive Guide for Optimal Returns

-

Asia2 months ago

Asia2 months agoChina’s 50% Domestic Equipment Rule: The Semiconductor Mandate Reshaping Global Tech

-

Global Economy3 months ago

Global Economy3 months agoPakistan’s Export Goldmine: 10 Game-Changing Markets Where Pakistani Businesses Are Winning Big in 2025

-

Analysis3 weeks ago

Analysis3 weeks agoTop 10 Stocks for Investment in PSX for Quick Returns in 2026

-

Global Economy3 months ago

Global Economy3 months ago15 Most Lucrative Sectors for Investment in Pakistan: A 2025 Data-Driven Analysis