Geopolitics

Global Cooperation Barometer 2026: Why International Collaboration Isn’t Dead—It’s Just Evolving [WEF Report Analysis]

While 123 million people were forcibly displaced in 2024—the highest number on record—global cooperation metrics held remarkably steady. This paradox lies at the heart of the World Economic Forum’s Global Cooperation Barometer 2026, a comprehensive analysis that challenges our assumptions about international collaboration in an age of rising tensions.

The third edition of this landmark report, developed in partnership with McKinsey & Company, reveals a nuanced truth: global cooperation isn’t collapsing—it’s transforming. Traditional multilateral frameworks may be straining under geopolitical pressures, but smaller, more agile coalitions are emerging to fill critical gaps in trade, technology transfer, climate action, and even security.

This evolution represents what UN Secretary-General António Guterres calls “hard-headed pragmatism”—the recognition that cooperation makes sense when it delivers tangible mutual benefits, even in a fragmented world.

What is the Global Cooperation Barometer 2026?

The Global Cooperation Barometer is an annual assessment by the World Economic Forum and McKinsey & Company that measures international collaboration across five key areas: trade and capital, innovation and technology, climate and natural capital, health and wellness, and peace and security. Using 41 metrics indexed to 2020, the 2026 edition finds overall cooperation held steady despite geopolitical tensions, but its composition shifted dramatically—from large multilateral frameworks toward smaller, flexible coalitions based on aligned interests and pragmatic problem-solving.

After analyzing 41 distinct metrics across five essential pillars—trade and capital, innovation and technology, climate and natural capital, health and wellness, and peace and security—the report’s central finding is clear: cooperation is adapting to new realities rather than disappearing entirely.

The Surprising Resilience of Global Cooperation

The 2026 Global Cooperation Barometer tracks international collaboration from 2012 through 2024, with all data indexed to 2020 as a baseline. This methodology, endorsed by OECD economists, allows researchers to isolate trends that emerged before the COVID-19 pandemic and those accelerated by it.

The topline finding? Overall cooperation levels in 2024 remained virtually unchanged from 2023, despite an environment characterized by:

- Escalating trade barriers and protectionist policies

- Multiple active military conflicts across three continents

- Heightened mistrust between major economic powers

- Record levels of forced displacement

- Increasing restrictions on technology transfers

According to Børge Brende, President and CEO of the World Economic Forum, “The paradox is that, at a time of such rapid change, developing new and innovative approaches to cooperation requires refocusing on some of the basics—notably, doubling down on dialogue.”

Understanding the Methodology

The barometer’s rigor lies in its comprehensive approach. Each of the five pillars comprises two indices:

- Action Index: Measures concrete cooperative behaviors (trade flows, knowledge exchange, financial transfers)

- Outcome Index: Tracks results of cooperation (life expectancy, emissions levels, conflict casualties)

Data is normalized to account for economic growth and population changes, ensuring that trendlines reflect genuine cooperation shifts rather than simple expansion. For example, trade metrics are measured as a percentage of global GDP, while migration data is normalized to global population levels.

This methodology, reviewed by International Monetary Fund economists, provides an apples-to-apples comparison across vastly different domains—from pharmaceutical R&D cooperation to peacekeeping deployments.

The Composition Shift That Matters

While aggregate cooperation held steady, the composition of that cooperation shifted dramatically. Metrics tied to global multilateral institutions—those large-scale frameworks involving most of the world’s nations—declined sharply:

- UN Security Council resolutions fell from 50 in 2023 to 46 in 2024

- Multilateral peacekeeping operations dropped by 11% year-over-year

- Official Development Assistance plummeted 10.8% in 2024

- International Health Regulations compliance weakened

Simultaneously, cooperation flourished in areas where flexible, interest-based partnerships could operate:

- Cross-border data flows surged, with international bandwidth now 4x larger than pre-pandemic levels

- Services trade continued its five-year growth trajectory

- Climate finance reached record levels, approaching $1 trillion annually

- Foreign direct investment in strategic sectors (semiconductors, data centers, EV batteries) accelerated

This divergence reveals a fundamental shift: from universal frameworks to tailored coalitions. As McKinsey’s research demonstrates, cooperation increasingly follows geopolitical alignment, with partners choosing collaborators based on shared interests and values rather than institutional membership alone.

Trade and Capital: Reconfiguration Over Retreat

The trade and capital pillar reveals perhaps the most complex story in the entire report. On the surface, cooperation appears flat—neither advancing nor retreating significantly. But beneath this stability, tectonic plates are shifting.

The Great Trade Rearrangement

According to World Trade Organization data analyzed in the report, global goods trade grew slightly slower than overall GDP in 2024, leading to a marginal decline in trade intensity. More revealing than the volume, however, is the geographic redistribution underway.

McKinsey Global Institute research finds that the average “geopolitical distance” of global goods trade fell by approximately 7% between 2017 and 2024. Countries are trading more with geopolitically aligned partners and less with distant ones—particularly between the United States and China.

The numbers tell a stark story:

- US imports from China fell 20% in the first seven months of 2025 compared to the same period in 2024

- Developing countries’ share of manufacturing exports rose by 5 percentage points in 2024

- China represented over half of this growth, adding $276 billion in exports

- Trade concentration (measured by the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index) declined by about 1%, indicating slight diversification

“We’re witnessing not deglobalization but reglobalization,” explains Dr. Richard Baldwin, Professor of International Economics at the Graduate Institute Geneva. “Trade relationships are being rewired along lines of trust and strategic alignment.”

The Silent Surge in Services and Capital

While goods trade reconfigured, less visible but equally important flows accelerated. Services trade—encompassing IT services, professional services, travel, and digitally delivered offerings—continued climbing throughout 2024.

According to UNCTAD data, services trade growth was driven primarily by:

- Digitally delivered services: IT consulting, cloud services, software development

- Business services: R&D, engineering, professional services

- Travel services: Rebounding from pandemic lows, though not yet at 2019 levels

Foreign direct investment told a similar story. While overall FDI flows remained complex (influenced by “phantom FDI” in tax havens), greenfield investment announcements—representing real productive capacity—surged in future-shaping industries.

FDI Markets data reveals a striking trend: newly announced greenfield projects concentrated heavily in:

- Semiconductors: $89 billion in announced projects globally

- Data centers and AI infrastructure: $370 billion (up from $190 billion in 2024)

- EV battery manufacturing: $67 billion

- Critical minerals processing: $34 billion

These investments flowed predominantly between geopolitically aligned partners. Advanced economies, particularly the United States, attracted the lion’s share, while China’s portion of announced FDI inflows dropped from 9% (2015-19 average) to just 3% (2022-25).

The Multilateral Casualty: Foreign Aid

The sharpest decline in the trade and capital pillar came in Official Development Assistance. According to OECD tracking, ODA fell 10.8% in 2024, with only four donor countries exceeding the UN target of 0.7% of gross national income.

The 2025 outlook appears even bleaker. The OECD projects an additional 9-17% decline in ODA, driven by:

- Reduced humanitarian aid budgets

- Decreased refugee spending in donor countries

- Lower aid to Ukraine as military assistance shifts

- Domestic political pressures in major donor nations

This trend has profound implications for low and middle-income countries that depend on international assistance for health systems, education, and infrastructure development.

New Coalition Models Emerge

Despite these challenges, innovative cooperation frameworks are sprouting. The Future of Investment and Trade (FIT) Partnership, launched in September 2025, brings together 14 economies—including Singapore, New Zealand, Switzerland, and the UAE—to pilot practical trade cooperation mechanisms.

According to Brookings Institution analysis, such “minilateral” arrangements offer several advantages over traditional multilateral treaties:

- Speed: Smaller groups reach consensus faster

- Flexibility: Tailored agreements address specific needs

- Resilience: Less vulnerable to any single member’s withdrawal

- Pragmatism: Focus on mutual gains rather than universal principles

Other examples include the EU-Mercosur trade agreement (after a decade of negotiations), the ASEAN Digital Economy Framework Agreement, and bilateral critical minerals deals between the US and allies like Australia and Canada.

Innovation and Technology: The AI Race Drives Selective Cooperation

The innovation and technology pillar registered a 3% year-over-year increase—one of the strongest performances across all five domains. Yet this growth masks growing tensions over technology transfer, particularly in areas deemed strategically sensitive.

The Data Flow Explosion

International bandwidth capacity quadrupled between 2019 and 2024, according to International Telecommunication Union statistics. Cross-border data flows—measured as a percentage of total internet traffic—continued their upward trajectory, fueled by:

- Cloud computing adoption accelerating globally

- Remote work normalizing post-pandemic

- Streaming services expanding internationally

- AI model training requiring distributed datasets

Cisco’s annual internet report projects that global IP traffic will reach 4.8 zettabytes per year by 2027, with a growing share crossing international borders.

This digital connectivity enabled a corresponding rise in IT services trade. Software development, cloud services, and AI consultation increasingly operate as global markets, with talent and expertise flowing across borders despite physical restrictions.

The Strategic Technology Paradox

Even as general technology cooperation flourished, restrictions tightened on specific advanced technologies. The United States expanded export controls on:

- Advanced semiconductors and chipmaking equipment

- AI training systems above certain computational thresholds

- Quantum computing components

- Certain biotechnology applications

According to McKinsey research on export controls, these restrictions primarily target China but ripple across global supply chains, affecting companies and research institutions worldwide.

The paradox? Cooperation in cutting-edge technologies continues—but increasingly within aligned blocs. Examples include:

US-Aligned Technology Partnerships:

- US-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET)

- US-EU Trade and Technology Council advancing AI safety standards

- US-Japan semiconductor research collaboration

- US-UAE framework on advanced technology cooperation

China-Led Technology Initiatives:

- 5G infrastructure partnerships across Southeast Asia and Africa

- AI research centers in Gulf states

- Data center investments in emerging markets

- Technology transfer agreements with Belt and Road countries

Foreign Affairs magazine describes this as “technological bifurcation”—not complete decoupling, but the emergence of parallel ecosystems with limited interconnection.

The Student Visa Squeeze

One concerning trend threatens long-term technology cooperation: declining international student mobility. After reaching record highs in 2024 (up 8% from 2023), international student flows appear to be contracting in 2025.

Data from major destination countries shows:

- United States: F-1 and M-1 student visas down 11% in Q1 2025

- United Kingdom: Student visa grants fell 2% year-over-year

- Australia: International student approvals dropped 64% (driven by new policy restrictions)

- Canada: Study permits declined amid new caps on international students

According to the Institute of International Education, this reversal could have long-term consequences for innovation. Historically, international students have contributed disproportionately to research breakthroughs, entrepreneurship, and cross-border knowledge networks.

Dr. Mary Sue Coleman, President of the Association of American Universities, warns: “When we restrict the flow of talent, we don’t just hurt international students—we diminish our own innovative capacity.”

The Productivity Question

Despite increases in most innovation metrics, one crucial outcome measure remained stubbornly flat: total factor productivity growth. The Conference Board’s data shows global productivity growth has stagnated for over a decade, raising questions about whether current cooperation patterns effectively translate into tangible economic benefits.

However, McKinsey Global Institute research suggests this may change. Generative AI could increase global productivity growth by 0.1 to 0.6 percentage points annually through 2040, but only if cooperation enables:

- Cross-border data access for model training

- International talent mobility for AI development

- Shared safety standards and governance frameworks

- Collaborative research on frontier applications

The question isn’t whether technology cooperation will matter—it’s whether current cooperation patterns will be sufficient to realize these gains.

Climate and Natural Capital: Deployment Rises, Outcomes Lag

The climate and natural capital pillar demonstrates both the promise and limitations of current cooperation patterns. Investment and deployment reached record levels, yet environmental outcomes continue deteriorating.

The Clean Energy Deployment Surge

Solar and wind capacity additions doubled between 2022 and 2024—from 300 to 600 gigawatts—according to the International Renewable Energy Agency. In the first half of 2025 alone, installations were 60% higher than the same period in 2024.

Remarkably, in the last 18 months, the world installed more solar capacity than in the previous three years combined.

International Energy Agency analysis attributes this acceleration to:

- Dramatic cost reductions: Solar module prices fell 90% over the past decade

- Global supply chains: Chinese manufacturing scale drove affordability

- Policy alignment: Domestic energy security goals converged with climate objectives

- Climate finance flows: Both public and private investment reached near $1 trillion annually

China accounted for two-thirds of solar, wind, and electric vehicle additions, but developing economies showed strong momentum. India became the world’s second-largest solar installer, while Brazil accelerated wind and solar deployment significantly.

The Natural Capital Challenge

While energy transition metrics improved, natural capital indicators stagnated or worsened:

- Marine protected areas: Growth stalled during 2023-24

- Terrestrial protected areas: Expansion slowed after steady progress

- Ocean Health Index: Continued gradual decline

- Biodiversity loss: Accelerated despite international commitments

The UN’s High Seas Treaty, reaching the required 60 ratifications in late 2025, offers hope. Entering force in January 2026, it creates the first legally binding framework for protecting two-thirds of the ocean beyond national jurisdiction.

Yet implementation remains uncertain, and the treaty faces the same multilateral pressures affecting other global agreements.

The Emissions Reality Check

Despite record clean energy deployment, global greenhouse gas emissions continued rising in 2024. Global Carbon Project data shows fossil fuel emissions reached approximately 37.8 billion tonnes of CO2 in 2024, up from 37.3 billion tonnes in 2023.

According to McKinsey Global Institute research, the energy transition is progressing at roughly half the speed needed to meet Paris Agreement goals of limiting warming to 1.5°C.

There is one encouraging trend: emissions intensity (emissions per unit of GDP) continues declining, demonstrating that economic growth can occur alongside emissions management—even if absolute reductions remain elusive.

Regional Climate Coalitions Take the Lead

As comprehensive global agreements prove challenging, regional cooperation is filling gaps:

European Union Initiatives:

- The Clean Industrial Deal (February 2025) aims to make decarbonization a competitive advantage

- The Net-Zero Industry Act accelerates manufacturing of clean technologies in Europe

- The Critical Raw Materials Act secures strategic inputs for the energy transition

- The EU-Central Asia Hydrogen Partnership (September 2025) creates new clean energy corridors

ASEAN Cooperation:

- The LTMS-PIP (Laos-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore Power Integration Project) enables cross-border clean power trading

- Progress toward an integrated ASEAN Power Grid enhances energy security while enabling renewable deployment

- The ASEAN Community Vision 2025 and Master Plan on ASEAN Connectivity both reached target dates with mixed implementation

COP30 Outcomes: The UN climate conference in Brazil produced several commitments:

- Tripling of adaptation finance by 2035

- Launch of the Tropical Forests Forever Facility to boost investment in protected areas

- New mechanisms for loss and damage funding

Climate Policy Initiative analysis notes that while these commitments are significant, the critical challenge remains implementation—translating pledges into deployed capital and measurable emissions reductions.

The Just Energy Transition Shortfall

One area of cooperation that significantly underperformed expectations: the Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs). These international financing mechanisms aim to assist emerging economies in transitioning to low-emission energy systems.

Despite commitments totaling $50 billion, only $7 billion had been delivered by June 2025—a 86% shortfall. According to World Resources Institute analysis, delays stemmed from:

- Bureaucratic complexity in mobilizing multilateral funds

- Competing domestic priorities among donor nations

- Difficulty coordinating between multiple financial institutions

- Recipients’ concerns about sovereignty and conditionality

This underperformance illustrates a broader challenge: while climate cooperation shows resilience in some areas (financing, trade, technology deployment), translating commitments into action remains difficult in the current geopolitical environment.

Health and Wellness: Resilient Outcomes, Eroding Support

The health and wellness pillar presents perhaps the most deceptive picture in the entire barometer. Overall cooperation appears stable—but this masks a dangerous erosion of the foundational support systems that enable positive health outcomes.

The Outcome Resilience

All major health outcome metrics improved in 2024, according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation:

- Life expectancy continued its post-pandemic recovery

- Child mortality (under-five) declined further

- Maternal mortality decreased in most regions

- Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) improved globally

These improvements reflect long-term developmental trends, post-pandemic normalization, and the cumulative effect of previous investments in global health systems.

However, health experts warn these improvements may prove temporary if current trends in health cooperation continue.

The Development Assistance Crisis

Development Assistance for Health fell 6% to $50 billion in 2024—continuing a three-year downward trend. IHME projections suggest an additional $11 billion decline in 2025, largely due to expected cuts from US funding agencies (approximately $9 billion).

Major donor reductions include:

- United States: PEPFAR (President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief) facing budget pressures; USAID tightening cost-sharing requirements

- United Kingdom: Continued retrenchment in global health spending amid domestic fiscal pressures

- Germany: ODA cuts affecting health assistance

According to World Health Organization officials, this creates a dangerous dynamic: bilateral health assistance increasingly focuses on direct service delivery (medicines, diagnostics, frontline care) while reducing support for health system infrastructure, training, and governance.

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director-General, describes this as “robbing Peter to pay Paul—we’re treating today’s patients while dismantling the systems needed to care for tomorrow’s.”

The Multilateral-Bilateral Shift

A significant trend emerged in 2024: funding through multilateral channels (WHO, Global Fund, multilateral development banks) fell by approximately 20%, while bilateral country-to-country funding declined only 3%.

This shift toward bilateral assistance has several implications:

Potential Benefits:

- More direct accountability between donor and recipient

- Faster deployment to specific needs

- Reduced bureaucratic overhead

- Clearer metrics for impact assessment

Significant Risks:

- System-level costs (training, governance, infrastructure) go unfunded

- Recipients face increased burden on domestic budgets

- Coordination between different bilateral programs weakens

- Political considerations may override health priorities

- Smaller countries with less strategic importance receive less support

Pandemic Preparedness in Limbo

The WHO Pandemic Agreement, adopted in May 2025 after three years of challenging negotiations, represents both an achievement and a disappointment in health cooperation.

On one hand, the agreement marks the first binding global framework for pandemic response, addressing lessons from COVID-19 around:

- Equitable access to vaccines and therapeutics

- Information sharing during outbreaks

- Research collaboration and pathogen surveillance

- Capacity building in low-resource settings

On the other hand, the United States—the world’s largest economy and historically the leading contributor to global health—did not participate in the agreement. This absence raises questions about the framework’s practical effectiveness.

Dr. Jennifer Nuzzo, Director of the Pandemic Center at Brown University School of Public Health, notes: “Treaties create obligations on paper, but pandemic preparedness requires sustained investment, trust, and coordination—all of which are in short supply in the current environment.”

Regional Health Cooperation Gains Ground

As global multilateral frameworks face pressure, regional cooperation showed promising developments:

Africa:

- The African Medicines Agency held its second session in Kigali (June 2025), advancing pharmaceutical regulatory harmonization

- The Accra Compact aligned African governments on health sovereignty priorities

- South Africa’s Aspen Pharmacare expanded COVID-19 vaccine manufacturing for the continent

Caribbean:

- The Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States scaled a model to reduce insulin prices region-wide

- Negotiations advanced on a Caribbean pharmaceutical procurement alliance

Latin America:

- Brazil’s Butantan Institute partnered with other regional manufacturers on vaccine development

- The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) strengthened regional disease surveillance

The Lancet, in a November 2025 editorial, described these developments as “pragmatic regionalism”—a recognition that health security increasingly depends on strong regional capacity rather than solely on global institutions.

The Healthspan-Lifespan Gap

One troubling trend that demands attention: while life expectancy continues rising, “health-adjusted life expectancy” (years lived in good health) lags behind. According to research published in JAMA Network Open, this means people are living more years with illness and disability.

This “healthspan-lifespan gap” varies significantly by geography and socioeconomic status, but it’s widening in most regions—suggesting that current health cooperation patterns, while extending life, may be less effective at ensuring those additional years are healthy and productive.

Peace and Security: The Pillar Under Greatest Strain

No pillar declined as sharply as peace and security. Every single metric tracked in this domain fell below pre-pandemic levels, reflecting an intensification of conflict and a weakening of multilateral conflict resolution mechanisms.

The Conflict Surge

The number of active conflicts increased in 2024, according to Uppsala Conflict Data Program. Major conflicts include:

- The ongoing Russia-Ukraine war (continuing into its third year)

- Israel-Hamas conflict in Gaza (beginning October 2023)

- Israel-Hezbollah hostilities (escalating in 2024)

- Civil war in Sudan (displacing 11.5 million people)

- Civil war in Myanmar (intensifying since 2021 coup)

- Intensified fighting in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo

Battle-related deaths remained near 2023 levels, with the Russia-Ukraine conflict accounting for over 40% of total fatalities.

The Displacement Crisis

Forcibly displaced people reached a record 123 million globally by the end of 2024, according to UNHCR. This represents an increase from 117 million in 2023 and 108 million in 2022.

The Sudan conflict alone displaced approximately 11.5 million people—the largest single-year displacement since Syria’s civil war peaked in 2013-2015.

Refugee flows strained hosting countries, particularly:

- Turkey (hosting 3.6 million Syrian refugees plus new arrivals)

- Pakistan (hosting Afghan refugees amid economic crisis)

- Uganda (hosting over 1.5 million refugees from multiple neighboring conflicts)

- Poland and other Eastern European nations (supporting Ukrainian refugees)

According to Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, the costs of supporting displaced populations fall disproportionately on middle-income countries neighboring conflict zones—countries that often lack the resources for adequate support.

Multilateral Mechanisms Under Pressure

The decline in multilateral peace and security cooperation manifested in several metrics:

UN Security Council:

- Resolutions decreased from 50 (2023) to 46 (2024)

- Vetoes by permanent members blocked action on several major conflicts

- The ratio of resolutions to active conflicts declined significantly

- Until November 2025, no new peacekeeping operation had been mandated since 2014

Peacekeeping Operations:

- The ratio of multilateral peacekeeping operations to conflicts fell by approximately 11% year-over-year

- Personnel deployed to multilateral peace operations declined by more than 40% between 2015 and 2024

- Budget constraints disrupted operations, with the approved UN peacekeeping budget falling from $9.7 billion (2014) to $4.7 billion (2025)

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute attributes these declines to:

- Geopolitical tensions among major powers limiting consensus

- Donor fatigue and budget pressures in contributing countries

- Questions about peacekeeping effectiveness in complex civil wars

- Host country sovereignty concerns limiting mandate flexibility

The Cyber and Grey-Zone Threat

Beyond traditional kinetic conflict, 2024 saw intensification of cyberattacks and “grey-zone” activities—actions that fall below the threshold of open warfare but still inflict significant damage.

Verizon’s 2025 Data Breach Investigations Report documents surging cyber incidents across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. High-profile attacks in 2024-25 included:

- Tata Motors’ Jaguar Land Rover halted production due to cyberattack (September 2025)

- Marks & Spencer faced up to £300 million losses from cyber breach (May 2025)

- Multiple critical infrastructure attacks across Europe

Physical infrastructure also came under attack through grey-zone operations:

- Sabotage of gas pipelines in Europe

- Damage to undersea internet cables in the Red Sea and West Africa (three major multi-cable outages)

- GPS jamming affecting civilian aviation

- Disinformation campaigns targeting elections in multiple democracies

Center for Strategic and International Studies analysis suggests these grey-zone activities are becoming the preferred tool for state and non-state actors seeking to achieve strategic objectives while avoiding direct military confrontation.

The Defense Spending Response

Countries responded to deteriorating security with increased defense budgets:

NATO:

- All 32 member states met the 2% of GDP defense spending target in 2025 (compared to fewer than 20 in 2024)

- The alliance raised its spending target to 5% of GDP for 2035 at The Hague Summit (June 2025)

Asia-Pacific:

- China continued double-digit defense budget increases

- Japan increased defense spending significantly, moving toward the 2% NATO target

- India expanded military modernization programs

- Australia boosted defense spending in response to regional tensions

European Union:

- The European Defence Agency reported increased spending across member states

- New EU defense industrial strategy launched to build autonomous capabilities

According to International Institute for Strategic Studies, global military expenditure reached approximately $2.4 trillion in 2024, representing roughly 2.2% of global GDP—the highest level since the early post-Cold War period.

Regional Peacekeeping Fills the Gap

Despite the decline in UN-led multilateral operations, regional bodies stepped up:

African Union:

- Led security transition in Somalia (ATMIS – African Union Transition Mission in Somalia)

- Deployed forces to eastern Democratic Republic of Congo

- Supported peacekeeping efforts in South Sudan

ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States):

- Maintained presence in several West African nations

- Coordinated responses to coups and instability in the Sahel

Arab League and GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council):

- Mediation efforts in Yemen

- Coordination on security challenges in the Red Sea corridor

United States Institute of Peace research suggests regional organizations often have advantages in peacekeeping:

- Better understanding of local contexts and dynamics

- Greater perceived legitimacy among parties to conflicts

- Ability to act when great power politics block global action

- More flexible mandates and lighter bureaucracy

However, these operations also face significant challenges, including limited resources, potential conflicts of interest among regional powers, and questions about impartiality.

Emerging Bright Spots in Conflict Resolution

Despite the overall decline, some successful examples of cooperation emerged in 2024-25:

Türkiye’s Mediation:

- The Ankara Declaration (February 2025) led to de-escalation of tensions between Ethiopia and Somalia

- Turkish diplomacy facilitated technical talks and confidence-building measures

Armenia-Azerbaijan Progress:

- The two nations agreed on the text of a peace treaty with EU and US facilitation

- Steps taken to keep third-country forces off borders reduced immediate escalation risks

Israel-Hamas Ceasefire:

- After 15 months of conflict, Qatar and Egypt mediated a ceasefire agreement in January 2025

- While fragile, the agreement created space for humanitarian access and reconstruction discussions

These examples underscore a theme throughout the barometer: while large-scale multilateral frameworks struggle, tailored diplomatic efforts by committed mediators can still yield results.

The Rise of Minilateralism: From Global to Agile

The single most important trend across all five pillars is the shift from universal, rules-based multilateralism toward smaller, flexible, interest-based coalitions.

Defining the New Cooperation Landscape

Multilateralism traditionally involved:

- Near-universal membership (180+ countries)

- Comprehensive frameworks (covering many issues)

- Consensus-based decision-making

- Institutional permanence (UN, WTO, WHO, etc.)

- Rules-based order with dispute resolution mechanisms

Minilateralism (sometimes called “plurilateralism”) instead features:

- Small groups of like-minded countries (3-20 members)

- Focused agendas (addressing specific challenges)

- Streamlined decision-making (easier consensus)

- Purpose-built arrangements (dissolving when objectives met)

- Pragmatic cooperation based on mutual interests

According to Council on Foreign Relations analysis, minilateralism offers several advantages in the current environment:

- Speed: Smaller groups negotiate and implement faster

- Flexibility: Tailored solutions address specific needs without compromising for universal buy-in

- Resilience: Less vulnerable to any single member’s withdrawal or obstruction

- Effectiveness: Clear objectives and accountable membership improve outcomes

- Complementarity: Can coexist with and supplement multilateral frameworks

Examples Across the Five Pillars

Trade and Capital:

- Future of Investment and Trade (FIT) Partnership (14 economies)

- EU-Mercosur trade agreement (after decade of negotiations)

- ASEAN Digital Economy Framework Agreement

- US-Australia-Japan-India Quad economic cooperation

- Bilateral critical minerals partnerships (US-Australia, US-Canada, US-Japan)

Innovation and Technology:

- US-India Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology

- US-EU Trade and Technology Council

- US-Japan semiconductor research collaboration

- US-UAE advanced technology cooperation framework

- Various AI safety research partnerships

Climate and Natural Capital:

- EU Clean Industrial Deal and regional decarbonization efforts

- LTMS-PIP Southeast Asian power grid integration

- EU-Central Asia Hydrogen Partnership

- Just Energy Transition Partnerships (despite underperformance, represent minilateral model)

Health and Wellness:

- African Medicines Agency regional pharmaceutical cooperation

- OECS insulin procurement collaboration (Caribbean)

- Accra Compact on African health sovereignty

- Various regional vaccine manufacturing partnerships

Peace and Security:

- African Union-led peacekeeping missions

- ECOWAS regional security coordination

- Türkiye-mediated bilateral negotiations (Ethiopia-Somalia, others)

- Quad security dialogue (US-Japan-Australia-India)

The Geopolitical Clustering Dynamic

McKinsey Global Institute research identifies a clear pattern: cooperation increasingly occurs within geopolitical blocs defined by shared values, security concerns, and economic interests.

Three broad clusters are emerging:

Western-Aligned Bloc:

- North America, Europe, developed Asia-Pacific (Japan, South Korea, Australia)

- Characterized by: democratic governance, market economies, security alliances (NATO, bilateral treaties)

- Deepening integration in technology, defense, critical supply chains

China-Aligned Bloc:

- China, Russia, some Central Asian nations, selective African and Latin American partnerships

- Characterized by: state-directed economics,alternative governance models, Belt and Road participation

- Growing integration in infrastructure, commodities, some technologies

Non-Aligned/Swing States:

- India, Brazil, Indonesia, Turkey, Gulf states, much of Africa and Latin America

- Characterized by: strategic autonomy, economic pragmatism, multiple partnerships

- Maintain relationships across blocs, optimize for national interests

Critically, these clusters are not rigid or exclusive. Many countries maintain relationships across boundaries, and cooperation patterns vary by issue area. India, for example, partners with the US on technology and security (Quad) while maintaining trade relationships with Russia and China.

The Dialogue Imperative

For this new cooperation landscape to function effectively, dialogue becomes more—not less—important.

As UN Secretary-General António Guterres emphasized in his September 2025 address to the General Assembly: “Taking steps forward to address global priorities can only happen if parties first talk with one another to find commonality.”

Yet dialogue quality has deteriorated. Too often, international engagements feature:

- Positioning statements rather than genuine exchange

- One-way communication designed to hold ground rather than find common ground

- Performative diplomacy focused on domestic audiences

- Tactical maneuvering instead of problem-solving

Effective dialogue in the minilateral era requires:

- Confidential channels: Away from public pressure and domestic political constraints

- Specific agendas: Focused on concrete problems with potential solutions

- Good-faith participation: Genuine willingness to find mutually beneficial outcomes

- Technical expertise: Subject matter experts alongside diplomats

- Follow-through mechanisms: Implementation plans with clear accountability

Harvard Negotiation Project research emphasizes that successful minilateral cooperation depends on participants separating people from problems, focusing on interests rather than positions, and generating options for mutual gain before deciding on specific approaches.

What the Shifting Cooperation Landscape Means for Global Business

The transformation in global cooperation patterns has profound implications for multinational corporations, investors, and business leaders navigating an increasingly complex environment.

The Corporate Sentiment Split

The Global Cooperation Barometer survey of approximately 800 executives across 81 economies revealed a striking divergence in perceptions:

- 40% reported that growing barriers in trade, talent, and capital flows hampered their ability to do business

- 60% said the effects were neutral or not substantially negative

This split suggests that business impacts depend heavily on:

- Industry: Technology and pharmaceuticals face more restrictions than services

- Geography: Companies operating between aligned partners less affected than those spanning geopolitical divides

- Business model: Digital platforms more adaptable than asset-heavy manufacturers

- Strategic positioning: Proactive adaptation mitigates negative effects

According to Harvard Business Review analysis, companies successfully navigating this environment share several characteristics:

- Geopolitical intelligence capabilities: Dedicated teams tracking regulatory changes, alliance shifts, and emerging restrictions

- Flexible supply chains: Multiple sourcing options and rapid reconfiguration ability

- Regional strategies: Tailored approaches for different geopolitical clusters

- Government relations excellence: Deep understanding of policy priorities and effective engagement

- Scenario planning: Regular war-gaming of geopolitical shocks and strategic responses

The Opportunity in Reconfiguration

While some business leaders focus on cooperation’s decline, others see opportunity in its transformation. McKinsey research identifies several emerging opportunities:

New Trade Corridors:

- Intra-ASEAN trade growing rapidly as regional integration deepens

- Africa-India trade expanding as both seek diversification

- Middle East-Europe connections strengthening (renewable energy, logistics)

- Latin American regional trade agreements creating larger effective markets

Strategic Industry Positioning:

- Semiconductor manufacturing expanding beyond East Asia (US, Europe, India investments)

- EV battery supply chains developing regional hubs (Europe, North America, Southeast Asia)

- Critical minerals processing diversifying away from China dominance

- Pharmaceutical manufacturing regionalizing for supply security

Services and Digital Growth:

- IT services demand surging as businesses digitize and adopt AI

- Professional services expanding as companies navigate complex regulatory environments

- Digital platforms less constrained by physical trade barriers

- Knowledge-intensive services benefiting from continued (if selective) talent mobility

Climate Transition Opportunities:

- $1 trillion+ annual climate finance creating massive market

- Clean technology manufacturing and deployment accelerating globally

- Energy transition requiring infrastructure investment across developing economies

- Carbon markets and climate services expanding

Building a Geopolitical Nerve Center

McKinsey research on geopolitical risk management recommends companies establish a dedicated “geopolitical nerve center”—a cross-functional team responsible for:

Monitoring and Intelligence:

- Track regulatory changes across jurisdictions

- Monitor geopolitical developments affecting operations

- Assess competitor positioning and strategic moves

- Maintain relationships with policy experts and government officials

Scenario Planning and War-Gaming:

- Develop detailed scenarios for potential geopolitical shocks (new sanctions, conflict escalation, alliance shifts)

- War-game company responses with senior leadership quarterly

- Identify trigger points for pre-authorized decisions

- Maintain updated playbooks for rapid response

Strategic Coordination:

- Align business unit strategies with geopolitical realities

- Coordinate government relations across regions

- Manage trade-offs between efficiency and resilience

- Balance short-term costs of adaptation with long-term risk reduction

Capability Building:

- Develop internal expertise on key geographies and issues

- Build relationships with external experts and advisors

- Train leadership on geopolitical risk assessment

- Foster cultural awareness and sensitivity

Companies that invested in these capabilities earlier are now outperforming. According to Boston Consulting Group analysis, firms in the top quartile of geopolitical preparedness showed 3-5 percentage points higher return on invested capital during 2022-24 compared to bottom-quartile peers.

Three Strategies for Navigating the New Cooperation Paradigm

As global cooperation evolves, leaders in both public and private sectors must adapt their approaches. Three strategies emerge from the barometer’s findings:

1. Match Cooperation Format to Specific Issues

Not all challenges require universal, multilateral solutions. Leaders should strategically choose cooperation formats based on:

Issue Characteristics:

- Technical problems with clear solutions: Small expert groups (e.g., technology standards)

- Economic opportunities with aligned incentives: Bilateral or regional trade agreements

- Security challenges with geographic concentration: Regional organizations

- Global challenges requiring universal participation: Reformed multilateral institutions (climate, pandemics)

Partner Alignment:

- High alignment: Deep integration possible (single markets, currency unions, defense alliances)

- Moderate alignment: Issue-specific cooperation (trade agreements, technology partnerships)

- Low alignment: Transactional engagement (commodity trade, specific projects)

Time Sensitivity:

- Immediate crises: Ad hoc coalitions of capable and willing actors

- Medium-term challenges: Purpose-built minilateral partnerships

- Long-term systemic issues: Institutional frameworks with staying power

The key is strategic flexibility—maintaining participation in multiple cooperation formats simultaneously, activating different partnerships for different challenges.

2. Strengthen Resilience Through New Organizational Capabilities

Both governments and businesses must build capabilities to thrive in a more fragmented cooperation landscape:

For Governments:

Intelligence and Foresight:

- Establish forward-looking analytical units tracking cooperation trends

- Maintain comprehensive mapping of existing partnerships and potential new ones

- Develop scenario planning for different cooperation futures

Diplomatic Agility:

- Train diplomats in minilateral negotiation techniques

- Empower smaller negotiating teams with flexible mandates

- Build rapid response capacity for emerging cooperation opportunities

Policy Coordination:

- Break down silos between trade, security, climate, and health policy

- Recognize interconnections across cooperation domains

- Develop whole-of-government strategies for key relationships

For Businesses:

Geopolitical Intelligence:

- Build dedicated teams monitoring regulatory and political developments

- Develop early warning systems for cooperation disruptions

- Maintain networks of advisors across key geographies

Operational Flexibility:

- Design supply chains with multiple sourcing options

- Maintain manufacturing and service delivery capacity in multiple regions

- Develop rapid reconfiguration capabilities

Strategic Relationships:

- Cultivate relationships with policymakers in key markets

- Participate actively in industry associations and multi-stakeholder forums

- Build trust through consistent engagement, not just during crises

According to McKinsey & Company research, companies that systematically built these capabilities showed higher revenue growth (2-4 percentage points annually) and lower volatility (15-25% lower earnings variance) compared to peers during 2020-24.

3. Pursue Public-Private and Private-Private Coalitions

Cooperation need not flow only through governmental channels. Innovative partnership models can accelerate progress:

Public-Private Coalitions:

These partnerships leverage complementary strengths:

- Government: Convening power, regulatory authority, patient capital, long-term perspective

- Business: Technical expertise, operational efficiency, innovation capacity, private capital

Successful examples include:

Minerals Security Partnership:

- Governments and leading mining/manufacturing companies

- Objective: Accelerate critical mineral projects

- Approach: Coordinated investment and market-making

- Result: Pipeline of projects moving toward financial close

Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI):

- Governments, foundations, pharmaceutical companies

- Objective: Accelerate vaccine development for emerging threats

- Approach: Coordinated R&D funding and manufacturing capacity

- Result: Rapid COVID-19 vaccine development and future preparedness

Private-Private Coalitions:

When public policy moves slowly, businesses can self-organize:

The Resilience Consortium (World Economic Forum/McKinsey):

- Brings together businesses’ agility, MDBs’ capital mobilization capacity

- Focus on building resilience in critical supply chains

- Enables rapid coordination without waiting for government action

Industry-Specific Standards Bodies:

- Technology companies collaborating on AI safety standards

- Pharmaceutical companies coordinating on pandemic preparedness

- Logistics companies optimizing supply chain resilience

According to World Economic Forum research, effective public-private partnerships share common characteristics:

- Clear governance: Defined roles, decision-making processes, accountability

- Aligned incentives: Structure ensuring all parties benefit from success

- Measurable objectives: Concrete targets and transparent progress tracking

- Risk sharing: Appropriate distribution of risks and rewards

- Long-term commitment: Patience through inevitable implementation challenges

Looking Ahead: Cooperation’s Future in 2026 and Beyond

As we move deeper into 2026, several trends deserve close attention:

Pressure Points to Watch

US Policy Direction:

- Tariff policies and their implementation affecting global trade flows

- Foreign aid levels impacting health and development cooperation

- Technology export controls shaping innovation ecosystems

- Immigration policies affecting talent mobility

China’s Strategic Choices:

- Economic opening or further self-reliance emphasis

- Technology cooperation with developing economies

- Belt and Road Initiative evolution

- Role in multilateral institutions

European Union Cohesion:

- Internal political dynamics affecting unity

- Defense spending and security cooperation expansion

- Industrial policy and subsidy competition

- Enlargement and neighborhood relations

Emerging Economy Agency:

- India’s positioning between major powers

- Gulf states’ technology and economic partnerships

- African regional integration progress

- Latin American trade and political alignments

Multilateral Institution Reform:

- UN Security Council reform discussions

- WTO dispute resolution restoration

- World Bank/IMF governance changes

- WHO funding and authority

Reasons for Measured Optimism

Despite significant challenges, several factors suggest cooperation’s resilience:

Economic Incentives Remain Strong:

- Global supply chains still deliver efficiency gains

- Cross-border investment creates wealth

- International students and workers enhance innovation

- Trade benefits consumers through lower prices and greater choice

Technology Enables New Forms:

- Digital platforms reduce coordination costs

- Data flows enable distributed collaboration

- Remote communication makes distance less relevant

- AI could enhance translation and cross-cultural understanding

Shared Challenges Demand Collective Action:

- Climate change affects all countries

- Pandemics ignore borders

- Cybersecurity threats require coordination

- Economic instability ripples globally

Pragmatic Leaders Understand Value:

- Surveys show majority recognize cooperation benefits

- Business leaders adapt strategies rather than retreat

- Diplomats seek creative solutions within constraints

- Civil society maintains cross-border networks

The Adaptation Imperative

The central message of the Global Cooperation Barometer 2026 is neither pessimistic nor naively optimistic. Instead, it offers a realistic assessment: cooperation is under pressure but adapting.

The question isn’t whether countries and organizations will cooperate—they will, because they must. The question is whether they’ll adapt quickly and effectively enough to address urgent challenges while managing tensions.

As Børge Brende of the World Economic Forum notes: “Cooperative approaches are vital for advancing corporate, national and global interests. The barometer finds that, in the face of strong headwinds, cooperation is still taking place, albeit in different forms than in the past.”

The path forward requires:

- Dialogue: Open, constructive engagement to identify common interests

- Flexibility: Willingness to try new cooperation formats and partnerships

- Pragmatism: Focus on tangible outcomes rather than ideological purity

- Patience: Recognition that building trust and achieving results takes time

- Innovation: Creative approaches to long-standing challenges

Conclusion: Cooperation Evolving, Not Collapsing

The 2026 Global Cooperation Barometer paints a nuanced picture of international collaboration in an era of geopolitical fragmentation. While traditional multilateral frameworks face unprecedented strain, cooperation persists and evolves through smaller, more flexible coalitions.

Across trade, technology, climate, health, and security—the five pillars of global cooperation—we see common patterns:

- Multilateral mechanisms declining but not disappearing entirely

- Regional and minilateral partnerships filling gaps with agile, interest-based cooperation

- Economic incentives continuing to drive collaboration where mutual benefits are clear

- Outcomes holding steady or improving in some areas, deteriorating in others

- Adaptability emerging as the key to navigating uncertainty

For business leaders, this environment demands new capabilities: geopolitical intelligence, supply chain flexibility, strategic relationship management, and scenario planning. Companies that proactively adapt can find opportunity in reconfiguration rather than merely managing decline.

For government officials and diplomats, success requires matching cooperation formats to specific challenges, building diverse partnership portfolios, and maintaining dialogue even—especially—with those with whom disagreement runs deep.

For all stakeholders, the fundamental truth remains: many of today’s most pressing challenges cannot be solved by any country or organization alone. Climate change, pandemic preparedness, economic prosperity, technological innovation, and peace all require cooperative effort.

The shape of that cooperation may look different from the post-World War II multilateral order. It may be more fragmented, more pragmatic, more selective about participants and more focused on concrete outcomes. But cooperation itself—the human capacity to work together toward shared goals—endures.

As we navigate 2026 and beyond, the barometer’s message is clear: cooperation isn’t dying. It’s evolving. And our collective ability to adapt will determine whether that evolution leads to a more resilient, prosperous, and peaceful world—or to continued fragmentation and missed opportunities.

The choice isn’t between cooperation and isolation. It’s between rigid adherence to fading frameworks and creative adaptation to new realities. The data suggests pragmatic optimism: cooperation is down but not out, strained but not shattered, adapting even as it’s tested.

In this era of transformation, the question each leader must answer is not “should we cooperate?” but “how shall we cooperate most effectively?” The Global Cooperation Barometer 2026 provides essential data for answering that question wisely.

Methodology Note: This article draws primarily from the World Economic Forum’s Global Cooperation Barometer 2026 Third Edition, produced in partnership with McKinsey & Company. All statistics are sourced from the report’s 41 tracked metrics unless otherwise noted. Additional reporting includes interviews with policy experts, analysis of supplementary data sources, and review of academic literature on international cooperation.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

Volodymyr Zelenskyy Says Ukraine War is at the ‘Beginning of the End’: Why He’s Urging Trump to See Through Russia’s Peace ‘Games’

Four years ago today, the world held its breath as Russian armor rolled toward Kyiv, expecting a sovereign nation’s rapid collapse. Today, on February 24, 2026, the geopolitical narrative has fundamentally shifted from sheer survival to the brutal, complex mechanics of a resolution. Standing in Independence Square near a makeshift memorial of flags honoring fallen soldiers, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy cast a profound look toward the future. But it was his candid, newly published Financial Times Zelenskyy interview that sent immediate ripples through the corridors of power in Washington, Brussels, and Moscow. The Ukraine war end is no longer a distant abstraction. We are, in his exact words, at the “beginning of the end.”

However, this final chapter is fraught with diplomatic landmines. As the world digests the latest Ukraine war updates, Zelenskyy’s core message wasn’t just directed at his weary citizens or European allies; it was a targeted, urgent plea to U.S. President Donald Trump. His goal? To ensure Washington doesn’t fall for the Russia games Trump might be tempted to entertain in his quest for a historic diplomatic victory.

“The Beginning of the End”: Decoding Zelenskyy’s Strategy

In international diplomacy, vocabulary is everything. By declaring the conflict is at the “beginning of the end,” Zelenskyy is signaling a transition from indefinite attrition to the tactical positioning that precedes an armistice. He is acknowledging the realities of a war-weary globe while firmly attempting to dictate the terms of the endgame.

In his extensive interview, Zelenskyy clarified that the “beginning of the end” does not equate to an immediate surrender or a hasty territorial compromise. Instead, it marks the phase where military stalemates force genuine structural negotiations. The recent trilateral Geneva negotiations on February 18, 2026, underscored this shift. Zelenskyy described the talks as arduous, noting that while political consensus remains out of reach, tangible progress was achieved on military de-escalation protocols.

“Putin is this war. He is the cause of its beginning and the obstacle to its end. And it is Russia that must be put in its place so that there is real peace.” — Volodymyr Zelenskyy, February 24, 2026

Seeing Through Putin’s “Games”: A Warning to Washington

The return of Donald Trump to the White House has undeniably accelerated the push for a negotiated settlement. Following the highly scrutinized Trump-Putin summit in Anchorage, Alaska, in late 2025, anxiety has permeated Kyiv. The underlying fear is that Washington might broker a transactional deal over Ukraine’s head, exchanging Ukrainian sovereignty for a perceived geopolitical win against the backdrop of rising U.S.-China tensions.

Zelenskyy’s challenge to the U.S. President is blunt: come to Kyiv. “Only by coming to Ukraine and seeing with one’s own eyes our life and our struggle… can one understand what this war is really about,” Zelenskyy stated during his anniversary address.

He explicitly warned that Trump Russia Ukraine tripartite dynamics are being actively manipulated by Moscow. During Putin peace talks, the Kremlin’s proposals are not olive branches but tactical Trojan horses—designed to weaken Kyiv’s negotiating position and exploit the new U.S. administration’s desire for a swift resolution. “The Russians are playing games,” Zelenskyy noted, stressing that the Kremlin has no serious, good-faith intention of ending the war unless forced by overwhelming leverage.

[Map of the current line of contact in Eastern Ukraine and proposed ceasefire monitoring zones]

The Mechanics of Peace: Security Guarantees and Ceasefire Monitoring

A ceasefire without enforcement is merely a tactical pause for rearmament—a painful lesson Ukraine learned between 2014 and 2022. This is the crux of the current diplomatic deadlock. However, the February 18 Geneva talks highlighted that military pragmatism is slowly taking shape.

Crucially, the sides have reportedly resolved the logistical framework for monitoring a prospective ceasefire, which would include direct US participation ceasefire oversight. This represents a massive geopolitical pivot, particularly given the Trump administration’s historical reluctance to commit American resources abroad, though it stops short of deploying U.S. combat troops.

To prevent a future invasion, Kyiv is demanding ironclad Ukraine ceasefire guarantees before any guns fall silent. As analyzed by foreign policy experts at The Washington Post, vague promises will not suffice.

Proposed Security Frameworks vs. Historical Precedents

| Framework | Core Mechanism | Deterrence Level | Sticking Points in 2026 Negotiations |

| NATO Membership | Article 5 Mutual Defense | Absolute | Russia’s ultimate red line; lingering U.S./German hesitation. |

| “Coalition of the Willing” | Bilateral defense pacts (UK, France, Germany) | High | Robust, but lacks a unified, legally binding U.S. enforcement mandate. |

| U.S.-Monitored Ceasefire | Armed/unarmed monitors along the Line of Contact | Moderate | Highly vulnerable to domestic political shifts in Washington; “mission creep” fears. |

| Budapest Memorandum 2.0 | Diplomatic assurances & promises | Low | Wholly rejected by Kyiv due to the catastrophic failures of 2014 and 2022. |

The Economic Battlefield: Tariffs, Sanctions, and EU Accession

You cannot divorce the geopolitical reality of the conflict’s resolution from the ongoing global macroeconomic shifts. As of February 2026, the international economy is digesting President Trump’s newly implemented 10% global tariff, creating a complex web of leverage and friction among Western allies.

For Ukraine, the endgame is not merely about drawing lines on a map; it is about securing the economic viability required to rebuild its shattered infrastructure and advance its European Union accession. According to insights from The New York Times, Western aid must now transition from emergency military provisions to long-term economic reconstruction capital.

[Chart illustrating the comparative economic contraction and recovery projections of Russia and Ukraine from 2022 to 2026]

Russia, meanwhile, continues to operate a hyper-militarized war economy. While Moscow projects resilience, the structural rot is becoming impossible to hide. The Bloomberg commodities index reflects how Western sanctions have forced Russia to pivot its energy exports to Asian markets at steep discounts, fundamentally restructuring the global energy grid and slashing the Kremlin’s long-term revenue streams.

The Economic Attrition of the War (2022–2026)

| Economic Metric | Ukraine | Russia | Global Macro Fallout |

| GDP Impact | Stabilizing with EU/US aid, but fundamentally altered. | Masked by unsustainable state war production; civilian sector starved. | Lingering supply chain shifts; restructuring of global defense budgets. |

| Energy Exports | Near-total loss of transit revenue; grid heavily damaged. | Forced pivot to Asia at heavy discounts; loss of premium European market. | Accelerated European transition to renewables and U.S. LNG. |

| Labor Force | Severe strain due to mobilization and refugee displacement. | Mass exodus of tech/skilled labor; severe labor shortages across industries. | European demographic shifts due to integration of Ukrainian refugees. |

Expert Analysis: The Realities of Global Geopolitics in 2026

When we analyze the Zelenskyy beginning of the end statement through the lens of geopolitics 2026, it is clear this is a calculated narrative pivot. As international relations researchers at The Economist note, Zelenskyy is preemptively framing the narrative. By calling out Russia’s “games” publicly, he is boxing the Trump administration into a corner where any concession to Putin looks like American weakness rather than diplomatic pragmatism.

Europe, meanwhile, is stepping up. The “coalition of the willing”—spearheaded by the UK, France, and a re-arming Germany—recognizes that the continent can no longer rely solely on the American security umbrella. If the U.S. forces a bitter peace, Europe will be left dealing with the fallout of an emboldened, revanchist Russia on its borders.

Conclusion: Forging a Durable Peace

The fourth anniversary of the full-scale invasion is a somber reminder of the staggering human cost of this conflict. As Zelenskyy urges Trump to visit Independence Square and witness the “sea of pain” firsthand, the message is unmistakable: peace cannot be signed on a spreadsheet or dictated from a summit in Alaska. It must be forged in reality, backed by unshakeable security guarantees, and grounded in the acknowledgment that rewarding aggression only guarantees future wars.

The “beginning of the end” is here. The question now is whether the Western alliance, led by a highly transactional U.S. administration, has the strategic patience to ensure that the end results in a lasting, just peace—or merely a countdown to the next conflict.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

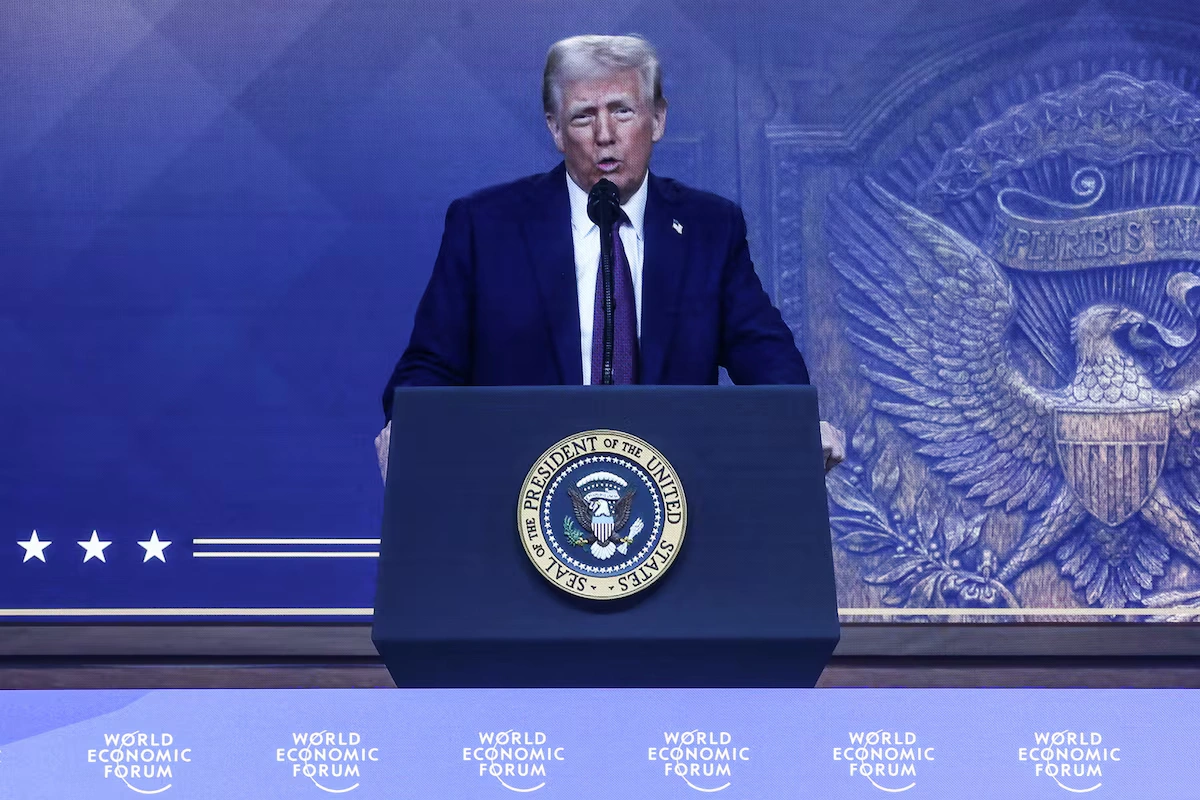

Trump’s 2026 State of the Union: Navigating Low Polls, Shutdowns, and Divisions in a Fractured America

Explore President Trump’s upcoming 2026 SOTU address amid record-low approval and political turmoil—insights on the US economy, immigration, and foreign policy shifts.

A year after reclaiming the White House in a historic political comeback, President Donald Trump will step up to the House rostrum on Tuesday at 9 p.m. ET to deliver his State of the Union address. The political climate he faces, however, is one of unusual fragility. Midway between his inauguration and the critical November midterm elections, this 2026 SOTU preview reveals a commander-in-chief confronting a partial government shutdown, rare judicial rebukes, and deep fractures within his own coalition.

When Trump last addressed Congress in March 2025, his approval rating hovered near a career high, buoyed by the momentum of his return to power. Today, he faces an electorate thoroughly fatigued by persistent inflation and systemic gridlock. Tuesday’s address is intended to showcase a leader who has unapologetically reshaped the federal government. Yet, as the Trump State of the Union amid low polls approaches, the spectacle will inevitably be weighed against the stark economic and political realities defining his second act.

Sagging Polls and Economic Realities

Historically, Trump has leveraged economic metrics as his strongest political shield. But the US economy under Trump 2026 presents a complicated picture for international economist researchers and everyday voters alike. According to recent data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis, while the stock market has seen notable rallies, 2025 marked the slowest year for job and economic growth since the pandemic-induced recession of 2020.

A recent Gallup tracking poll places his overall approval rating near record lows. Furthermore, roughly two-thirds of Americans currently describe the nation’s economy as “poor”—a sentiment that mirrors the frustrations felt during the latter half of the Biden administration. Grocery, housing, and utility costs remain stubbornly high. Analysts at The Economist note that the US labor market has settled into a stagnant “low-hire, low-fire” equilibrium, heavily exacerbated by sweeping trade restrictions.

| Economic & Polling Indicator | March 2025 (Inauguration Era) | February 2026 (Current) |

| Overall Approval Rating | 48% | 39% |

| Immigration Handling Approval | 51% | 38% |

| GDP Growth (Quarterly) | 4.4% (Q3 ’25) | 1.4% (Q4 ’25 Advance) |

| Economic Sentiment (“Poor”) | 45% | 66% |

Trump has vehemently defended his record, insisting last week that he has “won” on affordability. In his address, he is widely expected to blame his predecessor, Joe Biden, for lingering systemic economic pain while claiming unilateral credit for recent Wall Street highs.

Immigration Backlash and Shutdown Stalemate

Adding to the drama of the evening, Tuesday will mark the first time in modern US history that a president delivers the annual joint address amid a funding lapse. The partial government shutdown, now in its second week, centers entirely on the Department of Homeland Security.

Funding for DHS remains frozen as Democratic lawmakers demand stringent guardrails on the administration’s sweeping immigration crackdown. The standoff reached a boiling point following the deaths of two American citizens by federal agents during border protests in January. This tragic incident sparked nationwide outrage and eroded what was once a core political advantage for the President. An AP-NORC poll recently revealed that approval of Trump’s handling of immigration has plummeted to just 38%. The political capital he once commanded on border security is now deeply contested territory.

The Supreme Court Rebuke and Congressional Dynamics

Trump will be speaking to a Republican-led Congress that he has frequently bypassed. While he secured the passage of his signature tax legislation last summer—dubbed the “Big, Beautiful Bill,” which combined corporate tax cuts and immigration enforcement funding with deep reductions to Medicaid—he has largely governed via executive order.

This aggressive use of executive authority recently hit a massive judicial roadblock. Last week, the Supreme Court struck down many of Trump’s sweeping global tariffs, a central pillar of his economic agenda. In a pointed majority opinion, Trump-nominated Justice Neil Gorsuch warned against the “permanent accretion of power in the hands of one man.”

This ruling has massive implications for global trade. Financial analysts at The Financial Times suggest that the removal of these tariffs could ease some inflationary pressures, though Trump has already vowed to pursue alternative legal mechanisms to keep import taxes active, promising prolonged uncertainty for international markets.

Simultaneously, Trump’s coalition is showing signs of fraying:

- Demographic Shifts: Americans under 45 have sharply turned against the administration.

- Latino Voters: A demographic that shifted rightward in 2024 has seen steep drops in approval following January’s border violence.

- Intra-Party Apathy: Nearly three in 10 Republicans report that the administration is failing to focus on the country’s most pressing structural problems.

Trump Foreign Policy Shifts and Global Tensions

Foreign policy is expected to feature heavily in the address, highlighting one of the most unpredictable evolutions of his second term. Candidate Trump campaigned heavily on an “America First” platform, promising to extract the US from costly foreign entanglements. However, Trump foreign policy shifts over the last twelve months have alarmed both critics and isolationist allies.

The administration has dramatically expanded US military involvement abroad. Operations have ranged from seizing Venezuela’s president and bolstering forces around Iran to authorizing a lethal campaign of strikes on alleged drug-smuggling vessels—operations that have resulted in scores of casualties. For global observers and defense analysts at The Washington Post, this muscular, interventionist approach contradicts his earlier populist rhetoric, creating unease among voters who favored a pullback from global policing.

What to Expect: A Trump Midterm Rally Speech

Despite the mounting pressures, Trump is unlikely to strike a chastened or conciliatory tone. Observers should expect a classic Trump midterm rally speech.

“It’s going to be a long speech because we have a lot to talk about,” Trump teased on Monday.

Key themes to watch for include:

- Defending the First Year: Aggressive framing of the “Big, Beautiful Bill” and an insistence that manufacturing is successfully reshoring.

- Attacking the Courts and Democrats: Expect pointed rhetoric regarding the Supreme Court’s tariff ruling and the ongoing DHS shutdown.

- Political Theater: Democratic leader Hakeem Jeffries has urged his caucus to maintain a “strong, determined and dignified presence,” but several progressive members have already announced plans to boycott the speech in silent protest. For details on streaming the event, see our guide on How to Watch Trump’s State of the Union.

Conclusion: A Test of Presidential Leverage

For a president who has built a global brand on dominance and disruption, Tuesday’s State of the Union represents a profoundly different kind of test. The visual of Trump speaking from the dais while parts of his own government remain shuttered and his signature tariffs sit dismantled by his own judicial appointees is a potent symbol of his current vulnerability.

The core question for international markets and domestic voters alike is no longer whether Trump can shock the system, but whether he can stabilize it. To regain his footing ahead of the November midterms, he must persuade a highly skeptical public that his combative priorities align with their economic needs—and prove that his second act in the White House is anchored by strategy rather than adrift in grievance.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

The Asymmetric Stakes: Decoding the US China AI Race in 2026

The atmosphere at the India AI Impact Summit in New Delhi this February 2026 made one reality unavoidably clear: the US China AI race is no longer a straightforward sprint to a singular finish line. Instead, we are witnessing the entrenchment of an asymmetric bipolarity. For global economists, corporate strategists, and policymakers, the AI competition US China has evolved from a theoretical technology battle into a grinding, multipolar war over supply chains, energy grids, and the economic allegiance of the Global South.

To understand the true stakes of US vs China AI supremacy, we must discard the simplistic, moralizing narratives of Cold War 2.0. As an analyst watching the tectonic plates of the global economy shift, the reality is far more nuanced. The question of AI leadership US China is not merely about who builds the smartest chatbot; it is about who controls the underlying thermodynamics of the future economy.

In this comprehensive analysis, we will demystify the geopolitics of AI race dynamics, cutting through the hype to examine the real-time tradeoffs, capital constraints, and data-driven realities defining 2026.

The Illusion of a Single Finish Line in the US China AI Race

Western media often frames the US China AI race as a zero-sum game of frontier models. However, Time’s recent February 2026 analysis correctly notes that there are, in fact, multiple overlapping races. While the United States continues to dominate closed-source, highly capitalized frontier models, China has pivoted toward a radically different theory of value: rapid, low-cost diffusion.

The AI competition US China shifted permanently with the “DeepSeek shock” and the subsequent surge of open-source models. When Alibaba released Qwen 2.5-Max—surpassing 1 billion downloads globally—it proved that Chinese developers could achieve near-parity with US models at a fraction of the computational cost. As CNN reported in February 2026, China’s AI industry is utilizing algorithmic efficiency to circumvent hardware limitations.

This dynamic explains the pragmatic, if politically fraught, decision in January 2026 to loosen US export controls on Nvidia H200 chips. The move was a stark acknowledgment of global interconnectedness: starving China of chips entirely risks accelerating their indigenous semiconductor ecosystem while severely denting the bottom lines of American tech champions. In the battle for US vs China AI supremacy, capital requires market access just as much as it requires compute.

Key Divergences in the AI Competition US China

- US Strategy (Innovation & Capital): High-end chips, hyperscale data centers, closed-source models (OpenAI, Anthropic), and massive capital concentration.

- Chinese Strategy (Diffusion & Application): Open-source models (DeepSeek, Qwen), industrial deployment, legacy chip scale, and aggressive pricing to capture emerging markets.

The Core Battlegrounds: Compute, Chips, and Energy Bottlenecks

You cannot discuss the geopolitics of AI race dynamics without discussing thermodynamics. Artificial intelligence is, fundamentally, electricity transformed into computation. Here, the US vs China AI supremacy narrative takes a politically incorrect but entirely substantiated turn.

The US undeniably leads in compute. According to the Federal Reserve’s late-2025 data, the US commands a staggering 74% global share of advanced compute capacity. Furthermore, as Reuters reported, US AI investments are projected to hit $700 billion in 2026. However, American capital advantages face a severe domestic bottleneck: regulatory holdups and grid limitations. Building a hyperscale data center in the US requires navigating localized zoning, environmental reviews, and grid interconnection queues that can take years.

Conversely, China’s state-controlled model enables faster scaling of physical infrastructure. While the Brookings Institution’s January 2026 report highlights the contrasting energy strategies, the raw numbers are sobering. By 2030, China is projected to have 400 GW of spare energy capacity, heavily subsidized by state directives (Bloomberg, Nov 2025).

The Asymmetric Matrix: US vs China Advantages