Opinion

Pakistan’s Solar Push: Can Renewables Power Growth?

Introduction

Pakistan’s energy story has long been dominated by imported fossil fuels, chronic shortages, and rising costs. Yet, in 2025, a new narrative is unfolding: solar energy is emerging as a cornerstone of Pakistan’s economic future. With net-metered solar capacity reaching 5.3 GW by April 2025 out of a total installed generation capacity of 46,605 MW, the country is making strides toward a greener grid. But can renewables — particularly solar — truly power growth, or are structural challenges too steep?

🌞 Historical Context: Pakistan’s Energy Mix

- For decades, Pakistan relied heavily on thermal power (oil, gas, coal), which accounted for nearly 60% of generation in 2020.

- Hydropower contributed around 30%, while renewables were negligible.

- This dependence on imports strained foreign reserves, with energy imports costing over $20 billion annually by 2022.

📊 Current Solar Capacity & Targets

- Net-metered solar capacity: 5.3 GW (April 2025).

- Government targets: 40% renewable share by 2025 and 60% by 2030, already surpassing interim goals.

- World Bank projection: Solar and wind should reach 30% of total electricity capacity by 2030, equivalent to 24,000 MW.

- ADB forecast: Pakistan’s GDP growth at 2.7% in 2025, with inflation at 4.5%, highlighting the need for cheaper, stable energy.

💡 Economic Benefits of Solar

- Energy Security: Reduces reliance on imported oil and gas, easing pressure on foreign reserves.

- Job Creation: Solar installation and maintenance could generate hundreds of thousands of jobs by 2030.

- Cost Savings: World Bank estimates renewables could save Pakistan $5 billion over 20 years.

- Industrial Competitiveness: Affordable electricity boosts manufacturing, especially textiles and IT.

🚧 Challenges Ahead

- Grid Integration: Transmission capacity lags at 22,000 MW vs demand of 31,000 MW, causing outages.

- Financing: IMF notes Pakistan’s debt burden limits fiscal space for large-scale renewable projects.

- Policy Gaps: Recent 18% GST on imported solar panels risks slowing adoption.

- Equity Concerns: Solar adoption is faster among urban elites; rural and low-income households remain underserved.

🌍 Comparative Insights

- India: Installed over 80 GW of solar by 2025, leveraging subsidies and large-scale parks.

- Bangladesh: Pioneered solar home systems, reaching millions of rural households.

- Pakistan: Strong potential, but policy inconsistency and financing hurdles slow progress.

🔮 Future Outlook

- IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Facility: $1.3 billion allocated to Pakistan for climate-resilient infrastructure.

- Private Sector Role: Rooftop solar and battery storage are booming, with adoption quadrupling from 2024–2025.

- Global Context: Falling solar panel costs (down 80% since 2010) make renewables increasingly competitive.

✍️ Conclusion

Pakistan’s solar push is real and transformative, but fragile. The numbers show progress: capacity is rising, targets are ambitious, and economic benefits are clear. Yet, without grid upgrades, equitable financing, and consistent policy, solar alone cannot power sustainable growth.

In my view, Pakistan is not just entering a renewable era — it is at a crossroads. If policymakers align fiscal discipline with energy reforms, solar could become the backbone of Pakistan’s economic revival. If not, the promise of renewables risks being another missed opportunity.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Oil Markets

The US$100 Barrel: Oil Shockwaves Reach South-east Asia – And Could Hit $150

The ghost of 2022 is back to haunt the global economy, and its shadow looms darkest over Southeast Asia. As escalating conflict in the Middle East effectively shutters the Strait of Hormuz—the artery through which nearly 20% of the world’s oil flows—the price of Brent crude has violently surged past $114 a barrel, sending governments from Jakarta to Manila scrambling. This isn’t just a price spike; it’s a full-blown stagflationary shock threatening to derail the region’s fragile post-pandemic recovery, with some analysts now warning that $150 oil is no longer a distant fantasy.

The math is brutal. For every $10 increase in the price of oil, global GDP growth is trimmed by roughly 0.15 percentage points, while inflation gets a 0.4 percentage point boost. With oil jumping more than 25% in a matter of days, the impact is immediate and painful. From the Grab driver in Kuala Lumpur seeing his margins evaporate to the factory worker in Bangkok facing a higher cost of living, the US$100 barrel is a tax on everything. It’s a world of higher transport and food costs, ballooning fuel subsidy bills, and a gut-punch to consumer confidence.

From the Pump to the Plate: The Real-World Impact

The economic shockwave is radiating across the region, hitting each nation with unique force. The core issue is that most of Southeast Asia’s economies are massive net oil importers, leaving them dangerously exposed to global price swings.

- Philippines & Thailand: The Stagflation Crucible. These two nations are perhaps the most vulnerable. With a heavy reliance on imported energy, the pass-through to domestic inflation is rapid. The Thai baht and Philippine peso have weakened against a surging U.S. dollar, compounding the cost of imports. This leaves their central banks in an impossible position: raise rates to fight inflation and risk killing growth, or hold steady and watch purchasing power evaporate. Nomura has explicitly warned of a “stagflationary shock,” a toxic cocktail of stagnant growth and soaring prices that could lead to social and political instability.

- Malaysia & Indonesia: The Subsidy Black Hole. For years, these nations have used massive fuel subsidies to keep a lid on prices at the pump and maintain social harmony. But at over $100 a barrel, that strategy becomes fiscally ruinous. Indonesia’s Finance Minister has vowed to absorb the shock for now, but admits the state budget is under immense pressure. Malaysia, which was already planning to reform its subsidy program, now faces a monumental bill to shield its citizens. These subsidies, while politically popular, divert billions of dollars that could be spent on healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

- Singapore: A Crisis of Connectivity. As a global trade and finance hub with no natural resources, Singapore’s fate is tied to the free flow of goods and capital. While its direct energy consumption as a share of its economy is lower than its neighbors’, the island nation is hit by second-order effects. The effective closure of the Strait of Hormuz has thrown global shipping into chaos, with insurance premiums skyrocketing and vessels stranded. This spells higher costs for nearly everything Singapore imports and exports.

The Tourism Effect: Jet Fuel and Jittery Travelers

The oil shock extends beyond industry and into one of Southeast Asia’s most vital economic engines: tourism. The surge in crude prices directly translates to higher jet fuel costs, a major operating expense for airlines.

This pressure comes at a critical time for the region’s travel recovery. Destinations like Bali, Phuket, and Singapore, which have been banking on a strong 2026 travel season, now face the prospect of higher flight prices, which could deter long-haul visitors. Singapore has already moved to introduce a sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) levy for flights departing from Changi Airport starting this year, a necessary green step that will now be compounded by the oil price shock. The dream of an affordable tropical getaway is suddenly becoming more expensive, threatening to slow the flow of tourist dollars that support millions of jobs.

The Strait of Hormuz: A Geopolitical Powder Keg

The source of this economic earthquake is the geopolitical standoff in the Middle East. The effective closure of the Strait of Hormuz, whether by direct military action or the refusal of insurers to cover vessels, has created a de facto blockade. With around 15-20 million barrels of oil per day suddenly at risk, the market has reacted with predictable panic.

Analysts at Goldman Sachs and the IMF have warned that a sustained disruption could be catastrophic. Goldman’s upside scenario sees oil hitting $100 per barrel and shaving 0.4 percentage points off global growth. More alarmist predictions, including from analysts at Bloomberg, suggest a prolonged closure could send oil hurtling toward $150 or even $200 a barrel, a level that would almost certainly trigger a global recession. The crisis is not just about oil; it’s also a fertilizer shock, as a significant portion of the world’s urea and other key agricultural inputs transit the strait, threatening global food security.

The Road Ahead: $150 Oil and Difficult Choices

Is $150 oil a real possibility? If the Strait of Hormuz remains effectively closed for more than a few weeks, the answer is a terrifying yes. The world simply does not have enough spare production capacity to cover a shortfall of this magnitude.

This leaves Southeast Asian policymakers with a menu of painful options:

- Let prices float: Pass the full cost to consumers and businesses, risking mass public anger and a sharp economic contraction.

- Subsidize: Continue to burn through fiscal reserves to cap prices, mortgaging the future for short-term stability.

- Accelerate the green transition: Use the crisis as a catalyst to double down on renewable energy, electric vehicles, and energy efficiency. This is the long-term solution, but it provides little relief in the short run.

The US$100 barrel is more than a headline; it’s a structural shock that exposes the deep vulnerabilities of our globalized, fossil-fuel-dependent economy. For Southeast Asia, the coming months will be a brutal test of economic resilience, political will, and social cohesion. The shockwaves are already here, and the tsunami may be yet to come.

FAQs(FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS)

1. How does the Strait of Hormuz disruption affect Southeast Asia?

The Strait of Hormuz is a critical chokepoint for global oil shipments. Its closure disrupts supply, causing prices to surge. Since most Southeast Asian nations are net oil importers, they are forced to pay significantly more for energy, which drives inflation, strains government budgets, and slows economic growth.

2. Which countries in Southeast Asia are most at risk from $100 oil?

The Philippines and Thailand are considered highly vulnerable due to their heavy dependence on imported energy and the potential for a “stagflationary shock” (high inflation and low growth). Malaysia and Indonesia face massive fiscal pressure from their large fuel subsidy programs.

3. Could oil prices really reach $150 a barrel?

Analysts believe that if the disruption in the Strait of Hormuz is prolonged, oil prices could indeed spike to $150 or higher. This is because there is not enough spare oil production capacity globally to make up for the millions of barrels per day that transit the strait.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

KSE-100 Plunges Nearly 7% Amid Escalating Middle East Tensions: What It Means for Pakistan’s Economy

The digital clock on Mr. Ahmed’s trading terminal in Karachi’s bustling financial district had barely clicked past 9:15 AM when the screen turned a ghastly red, reflecting the collective dread that swept through the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX). His life savings, meticulously built over decades of cautious investment, seemed to evaporate with each precipitous drop in the KSE-100 Index.

“It’s not just numbers on a screen,” he’d often tell his children, “it’s the future of our family, the cost of our education, the roof over our heads.” Today, that future felt acutely fragile. The morning’s aggressive sell-off wasn’t merely a market correction; it was a visceral reaction to geopolitical tremors reverberating from distant shores, a stark reminder of Pakistan’s deep integration into a volatile global economy.

Why KSE-100 Fell Today: A Cascade of Geopolitical Risk

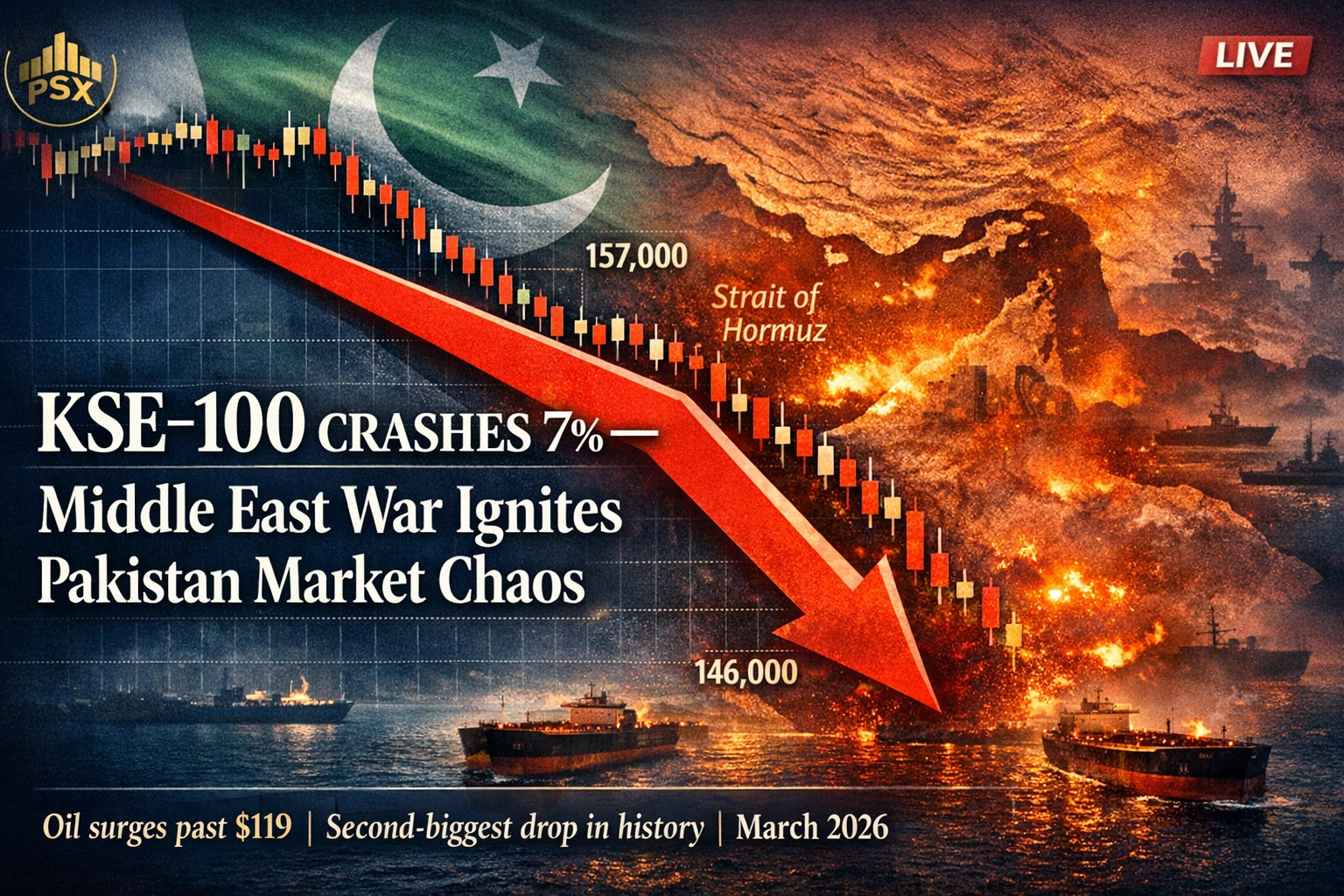

Monday, March 9, 2026, will be etched into the annals of Pakistan’s financial history as a day of profound market distress. The KSE-100 Index settled at 146,480.14, marking a stunning 11,015.96 points (or 6.99%) decline. This devastating fall, the second-highest single-day percentage drop in the index’s history, sent shockwaves across the nation’s financial landscape.

The day began with an immediate and aggressive sell-off, shedding 9,780.15 points (6.21%) by 9:22 AM. This dramatic freefall triggered a full market halt, as per PSX rules for circuit breakers, with the KSE-30 Index down 5%. Trading resumed precisely an hour later, at 10:22 AM, yet any hopes of a substantial recovery were dashed. A limited midday rebound gave way to a largely sideways and uncertain afternoon, as investors grappled with the unfolding global narrative.

The primary catalyst for this precipitous decline was unmistakably clear: escalating tensions in the Middle East. The deepening U.S.-Israeli conflict with Iran has unleashed a wave of uncertainty across global markets, but its impact is acutely felt in economies like Pakistan, highly dependent on imported energy. The immediate and most alarming fallout has been in the oil markets, with prices surging by an astounding ∼20% to multi-year highs, now exceeding $119 per barrel. Fears of disruption to the vital Strait of Hormuz, through which a significant portion of the world’s oil transits, have ignited a scramble for energy security and sent commodity markets into disarray [reuters_oil_surge_analysis].

A Troubling Precedent: KSE-100 Single-Day Decline 2026

The severity of today’s market performance is amplified by its historical context. Topline Securities research highlights a deeply concerning trend: the three largest single-day declines in the KSE-100’s history have all occurred in 2026. This alarming statistic suggests not merely a temporary blip, but potentially a new, more volatile paradigm for Pakistan’s equity markets, underscoring the fragility inherent in its economic structure in the face of external shocks.

Historically, Pakistan’s markets have shown resilience, navigating political upheavals, economic crises, and regional conflicts. However, the confluence of persistent domestic vulnerabilities — including perennial balance of payments issues, high public debt, and inflationary pressures — with intensified global geopolitical instability is creating a perfect storm. The market’s reaction today is a testament to the fact that while local factors are always at play, the sheer force of global events can swiftly overshadow them, particularly when they impinge on fundamental economic costs like energy.

Macroeconomic Fallout: Impact of Iran Conflict on Pakistan Stock Market

The implications of the surging oil prices and the wider Middle East conflict for Pakistan’s economy are profound and multifaceted.

- Inflationary Spiral: Pakistan is a net oil importer, making its economy highly vulnerable to global energy price shocks. A sustained increase in oil prices to over $119/barrel will inevitably translate into higher domestic fuel and power costs. This will directly feed into an already elevated inflation rate, eroding purchasing power and potentially triggering social unrest. The State Bank of Pakistan will face immense pressure to maintain tight monetary policy, further stifling economic growth [bloomberg_energy_crisis_inflation_shock].

- Rupee Depreciation & Balance of Payments Crisis: Higher oil import bills will place an unbearable strain on Pakistan’s foreign exchange reserves. This intensified demand for dollars to finance imports will inevitably lead to further depreciation of the Pakistani Rupee. A weaker rupee makes all imports more expensive, fueling a vicious cycle of inflation and exacerbating the balance of payments deficit. The central bank’s ability to defend the currency will be severely tested.

- IMF Programme Jeopardised: Pakistan is currently engaged in a critical International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme, which often hinges on fiscal discipline and external account stability. The unforeseen surge in oil prices could derail key macroeconomic targets, jeopardizing tranche disbursements and potentially leading to renegotiations or even suspension of the programme. This would send a catastrophic signal to international lenders and investors, further tightening access to much-needed external financing.

- FDI Flight and Investor Confidence: Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), always a sensitive indicator, is likely to pull back significantly. Global investors perceive Pakistan as an emerging market with inherent risks; escalating regional conflict and economic instability dramatically heighten that risk premium. The why KSE-100 fell today Middle East Iran war narrative sends a clear message of heightened risk, prompting a flight to safer assets and reducing the appetite for frontier market exposure.

- Energy Cost & Industrial Output: For Pakistan’s manufacturing and industrial sectors, higher energy costs mean reduced competitiveness and increased operational expenses. This could lead to factory closures, job losses, and a slowdown in economic activity, further dampening prospects for growth and poverty alleviation.

Global Echoes & Investor Lessons: Lessons from Past Crises

The current geopolitical and energy shock, while unique in its specifics, echoes past crises that have tested the resilience of emerging markets. Comparisons might be drawn to the oil shocks of the 1970s or the Asian Financial Crisis of the late 1990s, where external vulnerabilities coupled with internal imbalances created systemic risks. Bloomberg’s analysis of the Iran conflict’s impact on emerging markets [bloomberg_emerging_markets_fallout] highlights the fragility of recovery narratives when confronted with such potent external forces.

For international investors, today’s PSX trading suspended oil price surge 2026 event serves as a sharp reminder of the importance of geopolitical risk assessment, especially in regions with high energy import dependence and pre-existing economic fragilities. Diversification, hedging strategies, and a keen eye on global macro trends become not just advisable, but imperative. The KSE-100, once hailed for its potential, now stands as a cautionary tale of how quickly sentiment can turn amidst global uncertainty.

Outlook: Will Markets Stabilise?

The immediate outlook for the Pakistan Stock Exchange decline remains precarious. While the initial shock of the largest single-day falls KSE-100 history event has been absorbed, sustained market stability will depend on several critical factors:

- De-escalation in the Middle East: Any diplomatic breakthroughs or de-escalation of military tensions would provide immediate relief to oil markets and, by extension, to Pakistan’s economy. However, the current trajectory suggests a prolonged period of uncertainty.

- Global Oil Price Trajectory: If oil prices consolidate at or above $119/barrel, the economic headwinds for Pakistan will persist and intensify. A significant pullback in crude prices would offer a much-needed reprieve.

- Policy Response: The Government of Pakistan and the State Bank will need to demonstrate swift and decisive policy responses. This includes robust fiscal management to mitigate inflationary pressures, strategic foreign exchange interventions (if feasible), and clear communication with the public and international stakeholders to restore confidence. Austerity measures, however unpopular, may become unavoidable.

- International Support: The role of international financial institutions and friendly nations will be crucial. Access to emergency financing or favourable credit lines could provide a much-needed buffer against external shocks and prevent a full-blown financial crisis.

Conclusion: Navigating the Storm with Measured Hope

Today’s dramatic events on the Pakistan Stock Exchange are more than just a blip on the radar; they are a stark reflection of the interconnectedness of global finance and geopolitics. The KSE-100’s near 7% plunge underscores Pakistan’s acute vulnerability to external shocks, particularly when domestic economic fundamentals remain challenging.

For investors, both local and international, prudence is paramount. For policymakers, the path ahead demands decisive action, strategic foresight, and unwavering commitment to economic stability. While the immediate future appears fraught with challenges, Pakistan has a history of resilience. With judicious policy-making, transparent communication, and timely international support, the nation can hope to navigate these tempestuous waters. The human stories, like Mr. Ahmed’s, remind us that behind every market statistic lies real livelihoods, real aspirations, and a profound hope for a more stable tomorrow.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Analysis

SBP Holds Policy Rate at 10.5% as Middle East War Reshapes Pakistan’s Economic Calculus

The room at the State Bank of Pakistan’s Karachi headquarters may have been airconditioned on a warm Monday morning, but the temperature in global energy markets was anything but. As Governor Jameel Ahmad chaired the second Monetary Policy Committee meeting of 2026, Brent crude was careening past $103 a barrel — its highest since 2022 — while tanker traffic through the Strait of Hormuz had ground to a near-halt under the shadow of the US-Israeli war on Iran. The MPC’s decision, telegraphed by virtually every analyst in the market, arrived with unusual unanimity: the benchmark policy rate would stay unchanged at 10.5%.

It was a pause born not of confidence, but of calibrated caution — and perhaps the most consequential hold in Pakistan’s two-year monetary easing cycle.

SBP MPC Decision March 2026: What the Statement Actually Says

The official Monetary Policy Statement was diplomatically precise in framing the dilemma. “While the incoming data was largely consistent with the macroeconomic projections shared after the January meeting,” the MPC noted, “the Committee observed that the macroeconomic outlook has become quite uncertain following outbreak of the war in the Middle East.”

That single sentence encapsulates the entire complexity facing Pakistan’s central bank in March 2026: the domestic data looks broadly fine; the external world does not.

The MPC went further, identifying three concrete transmission channels through which the conflict is striking the Pakistani economy: a sharp rise in global fuel prices, elevated freight and insurance costs, and disruptions to cross-border trade and travel. “Given the evolving nature of events,” it added, “the intensity and duration of the conflict will both be important determinants of the impact on the domestic economy.”

In other words, the SBP is watching, not acting — and deliberately so.

Pakistan Interest Rate Hold: The Numbers Behind the Decision

To understand why the MPC held, it helps to survey the macroeconomic landscape that informed the room.

Inflation rebounding, but manageable — for now. After dipping as low as 3% mid-2025, Pakistani consumer price inflation climbed to 5.8% year-on-year in January 2026 and further to 7% in February — the upper edge of the SBP’s 5–7% medium-term target range. Core inflation has remained persistently sticky, hovering around 7.4% in recent months. The MPC had flagged at the January meeting that some months in the second half of FY26 could breach 7%; February’s print validated that warning precisely. With petrol prices raised by Rs55 per litre to Rs321.17 in the days before the meeting — a direct pass-through of the global energy shock — the domestic inflation trajectory has become materially more uncertain.

The external account: resilience with caveats. The current account posted a surplus of $121 million in January 2026, compressing the cumulative July–January FY26 deficit to just $1.1 billion. Workers’ remittances — a structural pillar of Pakistan’s external financing — continued to absorb a significant share of the trade deficit, while the SBP’s ongoing interbank foreign exchange purchases helped drive liquid FX reserves to $16.3 billion as of February 27, up from $16.1 billion in mid-January. The committee set a firm target of reaching $18 billion by June 2026 — a milestone that now depends critically on the timely realisation of planned official inflows, including disbursements under Pakistan’s $7 billion IMF Extended Fund Facility.

GDP momentum intact but under threat. Large-scale manufacturing growth has surprised to the upside this fiscal year, and the SBP maintained its GDP growth projection at 3.75–4.75% for FY26. Private sector credit expanded by Rs187 billion between July and November FY25, led by textiles, wholesale & retail, and chemicals. Consumer financing — particularly auto loans — has strengthened as financial conditions eased. But the current oil shock introduces a significant headwind: higher input costs, squeezed margins, and the prospect of renewed monetary tightening if inflation reaccelerates.

Pakistan Economy Risks: The Gulf Conflict Inflation Channel

The geopolitical backdrop informing this decision is arguably the most volatile since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and the MPC explicitly drew that parallel. “The macroeconomic fundamentals, especially in terms of inflation and the country’s FX and fiscal buffers, are better compared to the time of the start of the Russia-Ukraine war in early 2022,” the statement noted — a reassuring comparison, but one that implicitly acknowledges the severity of the threat.

Here is what has unfolded in the space of roughly ten days:

| Event | Market Impact |

|---|---|

| US-Israeli strikes on Iran begin (Feb 28) | Brent crude +25% in two weeks |

| Strait of Hormuz shipping near-halted | Freight & war-risk insurance surges |

| Iraq output collapses 60–70% | Global supply shortfall ~20 mb/d |

| Brent crude surpasses $103/bbl (Mar 9) | Highest since Russia-Ukraine shock |

| Qatar warns of $150/bbl risk | G7 emergency reserve discussions begin |

For Pakistan specifically, the pass-through arithmetic is sobering. The country imports virtually all of its crude oil requirements; historically, a $10 rise in Brent crude adds approximately 0.5–0.6 percentage points to Pakistan’s CPI within two to three quarters. With Brent having surged nearly $30 above its pre-conflict baseline, the potential inflation add-on over the coming two quarters — absent countervailing fiscal measures — could be 1.5–1.8 percentage points. That alone would push headline inflation toward 8.5–9%, well outside the target range and into territory that could force the SBP’s hand toward a rate increase.

The freight and insurance channel matters too. Pakistan’s exports — textiles, leather goods, surgical instruments — predominantly move by sea. War-risk insurance premiums for vessels transiting the Gulf region have spiked dramatically since late February, compressing export margins and threatening the competitiveness that the country has painstakingly rebuilt over the past eighteen months. Importers face mirror-image pressures: higher landed costs for energy, industrial inputs, and food commodities.

SBP Rate Decision Analysis: Why the Easing Cycle Has Effectively Paused

This is the SBP’s second consecutive hold — a sharp turn from the aggressive easing trajectory of the previous eighteen months. Between June 2024 and December 2025, the Monetary Policy Committee delivered a cumulative 1,150 basis points of rate cuts, bringing the policy rate down from a record 22% to 10.5%. That was one of the most dramatic easing cycles in any major emerging market during that period, and it was earned: inflation collapsed from multi-decade highs above 38% to the lower single digits, the rupee stabilised, and FX reserves rebuilt from critical lows.

The January 2026 hold surprised many analysts — Arif Habib Limited had pencilled in a 75bps cut to 9.75%, and a Reuters poll had pointed to a 50bps reduction — but it now reads as prescient caution. Governor Ahmad flagged at that press conference that inflation could breach 7% in some second-half months. It did, in February. The Middle East crisis then eliminated whatever residual space for cuts remained.

A Reuters poll conducted ahead of Monday’s meeting found near-unanimous consensus for a hold, with Topline Securities reporting that 96% of survey respondents expected no rate cut — a remarkable about-face from the 80% who had anticipated a cut ahead of January’s meeting. The shift in market expectations speaks to how quickly the geopolitical risk premium has repriced Pakistan’s monetary outlook.

The IMF’s own guidance reinforces the SBP’s caution. During its second programme review, the Fund urged that monetary policy remain “appropriately tight and data-dependent” to keep inflation expectations anchored and external buffers intact — language that sits uncomfortably with near-term rate cuts.

SBP FX Reserves and the External Account: A Fragile Resilience

Perhaps the most reassuring aspect of Monday’s statement was its treatment of the external account. The current account surplus in January, continued SBP interbank purchases, and the gradual rebuild of FX reserves to $16.3 billion all suggest that Pakistan enters this shock with considerably better buffers than it possessed in 2022 — when reserves plunged below $4 billion and the country teetered on the edge of sovereign default.

That buffer is real, but it is not inexhaustible. Three risks loom:

Oil import bill expansion. Pakistan’s monthly crude import bill will rise sharply if prices sustain above $100/bbl. The SBP’s current account deficit projection of 0–1% of GDP for FY26 was modelled on oil in the $70–80 range. A prolonged Hormuz closure tilts that range meaningfully toward the upper bound — or beyond it.

Remittance disruptions. A significant portion of Pakistani workers are employed in Gulf states — Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and Kuwait collectively host over 4 million Pakistani expatriates. Gulf economic disruption, energy revenue compression, and potential labour-market contraction in those countries could dampen remittance flows, removing a critical current account stabiliser.

Official inflow timing. The SBP’s $18 billion FX reserve target for June 2026 hinges on planned official inflows materialising on schedule. Geopolitical turbulence has historically caused IMF disbursement delays and bilateral lending hesitancy. Any slippage here would tighten the external constraint and, with it, the SBP’s room for manoeuvre.

Pakistan Economy Risks and Scenarios: Three Paths From Here

Scenario 1 — Rapid de-escalation (probability: low-medium). A swift US-Iran deal and Hormuz reopening within two to four weeks would allow oil prices to retreat toward $70–80/bbl, stabilise Pakistan’s import bill, and potentially reopen the door to a 25–50bps cut at the May 2026 MPC meeting. This is the base case for FY26 projections remaining intact.

Scenario 2 — Prolonged but contained conflict (probability: high). A six-to-eight week Hormuz disruption, with Brent stabilising in the $90–110 range, would push Pakistan’s CPI toward 8–9% in Q4 FY26 and FY27 Q1. The SBP holds through May and likely through July, pausing the easing cycle for two to three meetings. GDP growth dips toward the lower end of the 3.75–4.75% range.

Scenario 3 — Escalation and infrastructure damage (probability: low but non-trivial). Qatar’s energy minister has warned publicly that sustained Hormuz closure could drive Brent to $150/barrel — a scenario that Goldman Sachs estimates could add 0.7 percentage points to Asian inflation for every $15 oil price increase under a six-week closure. For Pakistan, that arithmetic implies a potential CPI overshoot to 10–12%. The SBP would be forced to consider a rate increase — a reversal that would set back the economic recovery significantly, pressure fiscal consolidation, and complicate the IMF programme.

Implications for Pakistani Borrowers, Investors, and Exporters

Corporate borrowers and SMEs: The 10.5% policy rate, while materially lower than the 22% peak, still represents a significant real financing cost for businesses. The hold — and the likelihood of an extended pause — delays the relief that industry bodies had anticipated from a return to single-digit rates. The Pakistan Business Council and various textile associations had lobbied for further cuts to restore export competitiveness.

Fixed-income investors: Government securities yields, which had been compressing in anticipation of further rate cuts, will likely stabilise or widen slightly at the short end as the hold extends. T-bill yields in the 10.5–11% range remain attractive in real terms relative to expected near-term inflation, but the duration risk on longer-tenor PIBs rises in a scenario where rate hikes become plausible.

Equity markets: The KSE-100 index, which had benefited significantly from falling rates and improving macro fundamentals, faces a more challenging environment. Energy sector stocks — particularly downstream oil marketing companies — face margin compression as import costs rise. However, the broader index may find some support from the fact that the SBP is holding rather than hiking, signalling that it views FY26 macroeconomic projections as still broadly achievable.

Exporters and remittance recipients: The PKR/USD exchange rate — which had stabilised in the 278–285 range — faces upward pressure from the widening trade balance. Topline Securities’ pre-MPC survey projected PKR stability in the 280–285 range through June 2026, a projection that assumes oil prices partially retrace from current peaks. Any significant rupee depreciation would create an imported inflation feedback loop that complicates the SBP’s task further.

Structural Reforms: The SBP’s Unanswered Question

Monday’s statement, like its January predecessor, reiterated the need for a “coordinated and prudent monetary and fiscal policy mix — as well as productivity-enhancing structural reforms — to increase exports and achieve high growth on a sustainable basis.” That language has appeared in virtually every MPC statement for years. It points to a fundamental vulnerability that no interest rate decision can resolve.

Pakistan’s export base, dominated by low-value-added textiles, has shown structural stagnation relative to regional peers. Its tax-to-GDP ratio — with FBR revenue growth decelerating to 7.3% in December 2025, well short of budgeted targets — remains among the lowest in Asia. Its energy import dependency leaves the current account structurally exposed to precisely the kind of shock that has arrived this week.

The SBP can hold rates, build reserves, and manage the short-term pass-through of oil prices. What it cannot do is substitute for the fiscal discipline, industrial policy, and governance improvements that would reduce Pakistan’s structural vulnerability to external shocks. The Gulf war has exposed that vulnerability with stark clarity.

Outlook: Cautious Resilience, Rising Risks

The SBP’s decision to hold at 10.5% was the right call for a central bank navigating a crisis of uncertain magnitude and duration. Pakistan enters this shock with better buffers than it possessed in 2022 — higher reserves, lower inflation, a stabilised currency, and an active IMF backstop. Those are not trivial advantages.

But the window for complacency is narrow. Brent crude at $103 and rising, a Hormuz chokepoint under active military threat, and a domestic inflation trajectory already touching the upper edge of the target range leave the SBP with limited runway. Governor Ahmad and his committee have effectively entered a watchful holding pattern: data-dependent, geopolitics-sensitive, and acutely aware that the next move could be a hike rather than a cut.

For global investors watching Pakistan’s emerging-market trajectory, the message is nuanced: the macro stabilisation story remains intact, but the risk premium has risen meaningfully. Sovereign spreads, equity valuations, and the rupee will all need to reprice for a world where $100+ oil is not a tail risk but a baseline.

The easing cycle that began in June 2024 is, for now, on hold. Whether it resumes — or reverses — depends on decisions being made not in Karachi, but in Washington, Tel Aviv, and Tehran.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

-

Markets & Finance2 months ago

Markets & Finance2 months agoTop 15 Stocks for Investment in 2026 in PSX: Your Complete Guide to Pakistan’s Best Investment Opportunities

-

Analysis1 month ago

Analysis1 month agoBrazil’s Rare Earth Race: US, EU, and China Compete for Critical Minerals as Tensions Rise

-

Banks2 months ago

Banks2 months agoBest Investments in Pakistan 2026: Top 10 Low-Price Shares and Long-Term Picks for the PSX

-

Investment2 months ago

Investment2 months agoTop 10 Mutual Fund Managers in Pakistan for Investment in 2026: A Comprehensive Guide for Optimal Returns

-

Asia2 months ago

Asia2 months agoChina’s 50% Domestic Equipment Rule: The Semiconductor Mandate Reshaping Global Tech

-

Global Economy2 months ago

Global Economy2 months agoPakistan’s Export Goldmine: 10 Game-Changing Markets Where Pakistani Businesses Are Winning Big in 2025

-

Global Economy2 months ago

Global Economy2 months agoWhat the U.S. Attack on Venezuela Could Mean for Oil and Canadian Crude Exports: The Economic Impact

-

Global Economy2 months ago

Global Economy2 months ago15 Most Lucrative Sectors for Investment in Pakistan: A 2025 Data-Driven Analysis