Governance

Beyond the Bailout: 10 Strategic Imperatives to Resolve Pakistan’s Balance of Payments Crisis

Executive Summary: The Structural Surgery Required

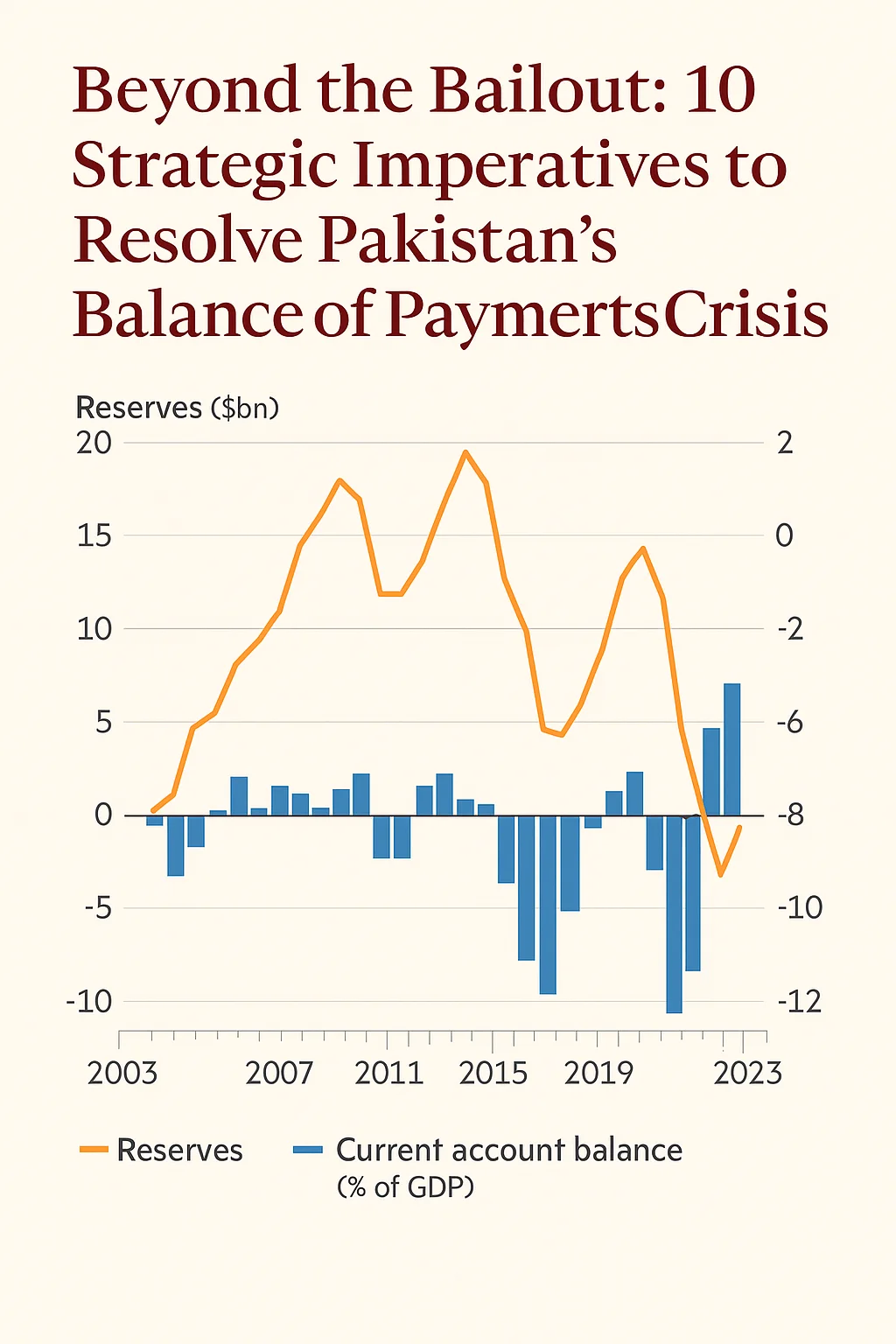

Pakistan’s economic history is defined by the “Stabilization Trap”—a recurring cycle where brief periods of consumption-led growth lead to a blowout in the Current Account Deficit (CAD), followed by emergency devaluations and IMF intervention. As of late 2025, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has managed a precarious stability, with foreign exchange reserves crossing the $14.5 billion threshold and inflation cooling to a multi-decade low of 4.5%. However, the structural fragility remains.

To transition from a debt-dependent economy to a trade-led powerhouse, Pakistan must implement a ten-pronged “structural surgery” that goes beyond mere belt-tightening. This article outlines the roadmap for the Finance Ministry, the SBP, and the Planning Commission to achieve a sustainable Balance of Payments (BoP).

1. Institutionalizing the Market-Determined Exchange Rate

The first line of defense in any BoP crisis is the exchange rate. According to the IMF’s latest review (December 2025), maintaining a market-determined exchange rate is non-negotiable for buffering external shocks.

For the SBP, the objective is not to “defend” a specific number, but to ensure liquidity. A market-aligned Rupee encourages expenditure-switching: it makes imports expensive and exports competitive. Historical data shows that whenever the REER (Real Effective Exchange Rate) is kept artificially low, the CAD explodes.

Policy Directive: The SBP must continue its policy of minimal intervention, allowing the currency to act as an automatic stabilizer for the trade balance.

2. Fiscal Consolidation: The Primary Surplus Mandate

Balance of Payments issues are often “twin deficits”—a fiscal deficit that fuels a current account deficit. The Ministry of Finance has achieved a historic primary surplus of 2.4% of GDP in FY25.

To maintain this, the government must resist the urge for “populist” spending. High fiscal deficits lead to increased domestic demand, which inevitably spills over into higher imports.

- The Target: Sustain a primary surplus above 2% for at least three consecutive fiscal cycles to signal fiscal discipline to global bond markets.

3. Aggressive Export Diversification (Beyond Textiles)

The World Bank’s Pakistan Development Update (October 2025) notes a sobering trend: Pakistan’s exports as a percentage of GDP have shrunk from 16% in the 1990s to roughly 10% today.

Textiles account for nearly 60% of goods exports, making the country vulnerable to global commodity price shifts.

- The Solution: Policy focus must shift toward high-value-added manufacturing (engineering goods, pharmaceuticals) and agriculture-tech (Basmati rice, value-added horticulture). The government should provide “Smart Subsidies” tied strictly to export performance milestones rather than blanket energy subsidies.

4. Scaling the “Digital Frontier”: IT and Services Exports

While goods trade often struggles with energy costs, IT services are Pakistan’s most agile export sector. In FY25, IT exports and remittances have become a primary pillar of BoP stability.

- The Opportunity: With global trade policy uncertainty rising, digital services are less susceptible to physical trade barriers.

- Action: The Planning Commission must fast-track “Special Technology Zones” (STZs) with 5G infrastructure and ease of repatriation for foreign earnings to encourage global tech firms to set up hubs in Karachi and Lahore.

5. Reforming the Energy Mix to Reduce the Import Bill

Energy typically accounts for 25-30% of Pakistan’s total import bill. The reliance on imported RLNG and furnace oil is a structural “leakage” in the BoP.

- Strategic Shift: Accelerate the transition to domestic coal (Thar) and renewables (Solar/Wind).

- The IMF Perspective: The Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF) recently approved by the IMF for Pakistan specifically targets this. Every 1% increase in domestic energy share saves roughly $200 million in foreign exchange annually.

6. Formalizing Workers’ Remittances

Remittances reached a record $38 billion in FY25, effectively offsetting a significant portion of the trade deficit. However, a portion of these flows still bypasses official channels via the Hundi/Hawala system.

- Policy Tool: The SBP must continue narrowing the gap between interbank and open-market rates.

- Innovation: Launch “Remittance Bonds” with tax-free incentives for overseas Pakistanis, allowing these flows to be funneled directly into national development projects rather than just household consumption.

7. Strategic Import Substitution: The “Make in Pakistan” Initiative

The government should incentivize the domestic production of intermediate goods—chemicals, steel, and mobile components—that currently drain billions.

Note of Caution: This is not a call for 1970s-style protectionism. Instead, the “National Industrial Policy” should focus on integrating Pakistani SMEs into global value chains, making it cheaper to produce locally than to import.

8. Attracting “Sticky” Capital: FDI over “Hot Money”

The BoP is currently propped up by official debt and short-term portfolio investment. This is high-risk.

- The ADB Roadmap: The Asian Development Bank (ADB) emphasizes private sector-led growth. Pakistan needs Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in productive sectors like mining and green energy.

- The SIFC Role: The Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) must move beyond MoUs to actual “ground-breaking” projects, ensuring a stable regulatory environment that guarantees profit repatriation.

9. Tight Monetary Policy to Anchor Inflation

The SBP has prudently kept the policy rate at a level where the real interest rate remains positive. High interest rates serve two purposes in a BoP crisis:

- They discourage domestic credit-fueled consumption (imports).

- They make domestic assets attractive to foreign investors, helping the Financial Account.

- Projection: As inflation stays in the 5–7% target range, the SBP can gradually ease rates, but only once the BoP surplus is structurally consolidated.

10. Expanding the Tax Base to Reduce Sovereign Borrowing

A low tax-to-GDP ratio (currently near 9-10%) forces the government to borrow externally to fund its budget, worsening the external debt profile.

- Focus: The FBR must pivot from taxing “easy” sectors (manufacturing/salaried) to the informal retail, real estate, and agriculture sectors.

- The World Bank View: Modernizing tax administration could unlock an additional 3% of GDP in revenue, significantly reducing the need for foreign-funded budgetary support.

Policy Trade-off Matrix: BoP Resolution Strategies

| Measure | Time to Impact | Political Cost | Official Source Alignment |

| Currency Realignment | Immediate | High (Inflationary) | IMF/SBP Mandate |

| Energy Transition | Long-term | Moderate | WB/RSF Support |

| IT Export Focus | Medium-term | Low | Planning Commission |

| Tax Base Expansion | Medium-term | Very High | FBR/IMF Requirement |

| Remittance Incentives | Fast | Low | SBP/Ministry of Finance |

Conclusion: The Path Ahead

The 2025 data suggests that Pakistan has secured a “breathing space,” with the first full-year current account surplus in over a decade ($2.1 billion). However, this surplus is largely driven by compressed demand and record remittances rather than a massive surge in industrial exports.

To ensure that the next growth cycle does not lead to another crash, the Finance Ministry and the State Bank must remain vigilant. The transition from stabilization to sustainable growth requires the political will to tax the untaxed and the economic vision to pivot toward a service-led, export-oriented future.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Global Economy

Trump’s December Address: The Reality Behind the Rhetoric

As approval ratings crater, the president’s primetime speech reveals a White House struggling to reconcile campaign promises with economic headwinds

When President Trump declared from the Diplomatic Reception Room on Wednesday evening that he had “inherited a mess” and was now “fixing it,” he unknowingly captured the central paradox of his second term. Nearly eleven months into his presidency, Trump claims to have brought “more positive change to Washington than any administration in American history,” yet this assertion collides uncomfortably with economic data showing Americans increasingly pessimistic about their financial futures. The disconnect between the president’s triumphalist rhetoric and voters’ lived experience isn’t merely a messaging problem—it’s become a political crisis that threatens Republican control of Congress in 2026.

The most revealing aspect of Trump’s address wasn’t what he announced, but what he avoided. Beyond unveiling a $1,776 “warrior dividend” for military personnel—a $2.5 billion expenditure funded by tariff revenues—the twenty-minute speech broke little new policy ground. Instead, it offered a familiar litany of achievements, exaggerated statistics, and blame directed at his predecessor. What went unmentioned speaks volumes: Trump’s economic approval has plummeted to just 36% according to the latest NPR/PBS News/Marist poll, marking the lowest point of either of his presidential terms. For a politician who built his brand on economic competence, this represents a devastating reversal.

The Affordability Crisis Trump Can’t Spin Away

The numbers tell a story Trump’s rhetoric cannot obscure. Sixty-eight percent of Americans, including 44% of Republicans, now say the economy is in poor shape, according to the Associated Press-NORC survey conducted in early December. Perhaps more troubling for the White House, 45% of Americans identify prices as their top economic concern—more than double the next highest category. This isn’t abstract economic anxiety; it’s concrete kitchen-table distress.

Trump claimed gasoline now costs under $2.50 per gallon “in much of the country,” but AAA data shows the national average at $2.90—only 13 cents lower than a year ago. His assertion that egg prices have fallen 82% since March, while directionally accurate about wholesale prices, masks a more complex story about supply chain disruptions and avian flu recovery. These selective statistics reveal a White House more focused on crafting favorable narratives than addressing underlying economic pressures.

The president’s boast about solving grocery price inflation rings particularly hollow. While it’s true that some commodity prices have moderated, 70% of Americans now describe the cost of living as “not very affordable” or “not affordable at all”—the highest level since Marist began tracking this measure in 2011. Just six months earlier, only 45% expressed similar concerns. This dramatic deterioration in perceived affordability represents one of the sharpest swings in consumer sentiment in recent memory.

The Tariff Trap: When Economic Theory Meets Political Reality

Trump’s warrior dividend announcement inadvertently highlighted the administration’s central economic gamble: that tariff revenues can fund government priorities without imposing costs on American consumers and businesses. This assumption has proven spectacularly wrong.

The Tax Foundation estimates that Trump’s imposed tariffs will reduce U.S. GDP by 0.5% and amount to an average tax increase of $1,100 per household in 2025, rising to $1,400 in 2026. These aren’t abstract economic projections—they’re manifesting in real-world price increases across sectors. Research by Harvard economist Alberto Cavallo and colleagues found that the inflation rate would have been 2.2% rather than current levels had it not been for Trump’s tariffs.

The political consequences are becoming apparent. Two-thirds of Americans express concern about tariffs’ impact on their personal finances, while business uncertainty has contributed to a dramatic slowdown in hiring. November saw just 64,000 jobs added, while October recorded a loss of 105,000 positions, driven largely by federal workforce reductions but exacerbated by private sector caution. The unemployment rate climbed to 4.6%—the highest level in four years.

Small businesses bear a disproportionate burden. Unlike large retailers with sophisticated supply chains and pricing power, small importers face existential pressure. One small business owner told CNBC that complexity in her supply chain has increased tenfold, while revenue has declined year-over-year. With approximately 36 million small businesses accounting for 43% of U.S. GDP, their struggles have macroeconomic implications that extend far beyond individual balance sheets.

The Midterm Mathematics Don’t Add Up

Trump’s address comes as Republicans confront an uncomfortable political reality: the affordability message that propelled them to victory in 2024 has become a vulnerability. Recent Quinnipiac polling shows only 40% of Americans approve of Trump’s job performance, with 54% disapproving, while his economic approval sits even lower. Among critical swing constituencies, the erosion is severe—rural voters and white women without college degrees, both core Republican groups, now disapprove of his economic stewardship by significant margins.

The November off-year elections offered a preview of potential 2026 outcomes. Democrats swept gubernatorial races in Virginia and New Jersey, and captured the New York City mayoralty—all by centering campaigns on affordability and cost-of-living concerns. In an echo of the Republican playbook from 2024, progressive candidates successfully framed GOP economic policies as benefiting corporations while hurting families. The political tables have turned with stunning speed.

Historical precedent suggests danger ahead. Trump’s overall approval stands at 38% in some surveys—comparable to his April 2018 rating, which preceded Republicans losing 40 House seats in the midterm elections. The intensity of disapproval is particularly concerning; 50% of registered voters say they “strongly disapprove” of the president’s performance, a level of polarized opposition that typically drives high opposition turnout.

The Federal Reserve Dilemma

Trump’s promise to announce “someone who believes in lower interest rates by a lot” as the next Federal Reserve chairman reveals a fundamental misunderstanding—or deliberate misrepresentation—of monetary policy constraints. The Fed faces a trilemma: supporting growth, controlling inflation, and maintaining dollar stability. Trump’s tariff policies have made this balancing act significantly more difficult.

Average hourly earnings rose just 0.1% in November, suggesting wage pressures remain subdued. Yet inflation persists at around 3%—above the Fed’s 2% target and sticky enough to limit aggressive rate cuts. The November jobs report, showing unemployment at a four-year high alongside sluggish hiring, presents precisely the stagflationary scenario that gives central bankers nightmares.

Political pressure on the Fed to prioritize growth over inflation stability could undermine the institution’s credibility, risking long-term economic damage for short-term political gains. Markets appear skeptical; despite Trump’s optimistic projections, probability of a January rate cut remains low, with traders pricing in limited easing through 2026.

What Wasn’t Said Matters More Than What Was

The twenty-minute address notable omissions reveal a White House in damage-control mode. Trump made no mention of health care, despite millions of Americans facing higher premiums in 2026 due to expiring Affordable Care Act subsidies—a crisis that contributed to the recent government shutdown. He offered no concrete plan to address housing affordability, despite promising “some of the most aggressive housing reform plans in American history.” These vague future commitments suggest policy initiatives remain underdeveloped even as political pressure mounts.

Perhaps most tellingly, Trump avoided discussing the budget deficit or federal debt, despite his tariff-for-revenue strategy falling short of financing goals. The warrior dividend, while symbolically appealing, exemplifies the problem: using trade policy to fund discrete initiatives without addressing systemic fiscal challenges. It’s governance by announcement rather than comprehensive planning.

The Road Ahead: Campaign Mode Cannot Solve Governing Challenges

The address “had the feel of a Trump rally speech, without the rally,” one observer noted—an apt description of an administration struggling to transition from campaign mode to governing reality. Rally rhetoric energizes the base but doesn’t lower grocery bills or create jobs. As Democrats discovered during Biden’s tenure, economic perception often matters more than economic statistics, and perception has turned decisively negative.

Trump faces an increasingly narrow path forward. His approval among Republicans remains robust at around 84%, providing a stable floor but insufficient for broader political success. To rebuild credibility on economic management, the administration needs to deliver tangible affordability improvements before the 2026 midterm campaign begins in earnest—likely by summer 2026.

Three potential scenarios emerge. First, the administration could scale back tariffs, accepting short-term political embarrassment to ease price pressures and business uncertainty. Second, the White House might pursue aggressive fiscal stimulus, risking inflation but boosting consumer spending power. Third—and most likely—Trump continues doubling down on his current approach, gambling that economic conditions improve independently or that he can successfully blame Democrats for ongoing problems.

The December address suggests the third path. Trump spent more time deflecting blame toward Biden than outlining forward-looking solutions. This backward-looking posture may satisfy core supporters but does little to win back skeptical independents and suburban voters whose support determines congressional majorities.

The Bigger Picture: Populism Meets Economic Reality

Trump’s predicament illustrates a broader challenge facing populist economic nationalism: converting campaign slogans into sustainable policy proves considerably harder than winning elections. Tariffs were supposed to protect American workers, rebuild manufacturing, and generate government revenue—a win-win-win proposition. Instead, they’ve produced a lose-lose-lose outcome: higher consumer prices, business uncertainty dampening investment and hiring, and insufficient revenue to offset their economic drag.

The president’s address revealed an administration caught between its ideological commitments and economic realities. Unable to acknowledge that signature policies might be failing, yet unable to convince voters that those policies are succeeding, Trump has retreated into an increasingly defensive crouch. The warrior dividend—a one-time payment to a politically sympathetic constituency—exemplifies the thinking: targeted gestures to shore up support rather than comprehensive solutions to systemic problems.

As the 2026 midterms approach, Republicans face an uncomfortable question: Can Trump’s personal political skills overcome objective economic headwinds? History suggests the answer is no. Midterm elections typically serve as referendums on presidential performance, particularly economic performance. With affordability concerns at fourteen-year highs, unemployment rising, and business confidence weakening, the political environment increasingly resembles 2018’s Democratic wave election—only in reverse.

The December address offered reassurance to supporters but did little to expand the coalition Trump needs to maintain congressional majorities. Perhaps that was always its purpose: shoring up the base rather than persuading skeptics. If so, it represents a strategic retreat from the ambitious claims that opened the speech. Bringing “more positive change than any administration in American history” requires more than declaring it—it requires delivering results that voters can see and feel. On that metric, Trump’s second term remains very much a work in progress, and patience is wearing thin.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Global Finance

Pakistan’s IMF Deal: Reform or Recoil?

As Pakistan enters yet another phase of IMF‑mandated reform, the country stands at a familiar crossroads: the tension between sovereignty and sustainability. The IMF’s latest Staff Report Directives—an 11‑point matrix of governance, fiscal, and sectoral reforms—signal a shift from short‑term stabilization to long‑delayed structural overhaul. But can a politically fragmented state absorb the socio‑economic shockwaves these reforms will unleash?

To understand the magnitude of the challenge, the conditions can be grouped into three analytical pillars: Governance & Transparency, Fiscal Consolidation, and Sectoral Liberalization. Each pillar carries its own economic rationale—and its own political landmines.

A. Governance & Transparency: The Anti‑Corruption Mandate

At the heart of the IMF’s governance agenda lies a symbolic yet politically explosive requirement: mandatory asset declarations for all federal civil servants by December next year, followed by provincial-level disclosures by October. According to the IMF Staff Report Directives, this measure is intended to operationalize the recommendations of the Governance Diagnostic Report and align Pakistan with global transparency norms.

“Pakistan’s path to sustainability demands a surrender of fiscal sovereignty—starting with bureaucratic transparency and ending with sectoral disruption.”

On paper, the economic logic is straightforward. Transparency reduces corruption risk, improves investor confidence, and strengthens institutional credibility. The World Bank’s simulated “Governance Effectiveness Index” suggests that countries with mandatory public disclosures experience a measurable improvement in FDI inflows over a five‑year horizon.

But the socio‑political cost is far from trivial.

Pakistan’s bureaucracy—one of the most entrenched power centers in the country—views asset disclosure as an existential threat. Resistance is likely to be fierce, particularly from senior cadres who perceive the requirement as an erosion of administrative sovereignty. Will a bureaucracy accustomed to opacity willingly embrace radical transparency?

The IMF’s demand for amendments to the Companies Act, 2017 and the SECP Act further deepens the governance overhaul. These changes aim to align corporate governance with international best practices, a move consistent with ADB’s Regional Economic Outlook, which has repeatedly flagged Pakistan’s weak regulatory enforcement as a barrier to private‑sector growth.

Economic Outcome: Improved governance, reduced corruption risk, enhanced investor confidence.

Political Cost: Institutional pushback, bureaucratic inertia, and potential legal challenges.

B. Fiscal Consolidation: Taxes, Mini‑Budgets, and the Politics of Pain

The second pillar—fiscal consolidation—is the most politically combustible. The IMF has explicitly tied program continuity to Pakistan’s ability to meet revenue targets by end‑December 2025, failing which a mini‑budget will be required. This is not merely a fiscal safeguard; it is a structural test of Pakistan’s political will.

Among the most contentious measures are:

- A 5% increase in federal excise duty on fertilisers and pesticides

- New excise duties on high‑value sugary items

These taxes are economically rational but politically radioactive.

The agricultural lobby—one of the most powerful in Pakistan—will resist higher input costs, arguing that the duty increase will raise food inflation and depress rural incomes. Meanwhile, the sugary‑items tax directly targets the influential sugar lobby, a group with deep political roots and cross‑party influence. The IMF’s insistence on these measures reflects a broader push to expand Pakistan’s chronically narrow tax base, which the World Bank estimates captures less than 10% of potential taxpayers.

But what is the socio‑economic trade‑off?

Higher taxes on sugary items may reduce consumption and improve public health outcomes, but they will also raise retail prices in an already inflation‑sensitive consumer market. The fertiliser and pesticide duty increase risks pushing up agricultural production costs, potentially feeding into food inflation—a politically sensitive metric in any emerging market.

Economic Outcome: Revenue expansion, reduced fiscal deficit, alignment with IMF sustainability benchmarks.

Political Cost: Rural backlash, industry lobbying, inflationary pressure, and heightened risk of street‑level protest.

C. Sectoral Liberalization: Power and Sugar—The Twin Fault Lines

The third pillar—sectoral liberalization—targets two of Pakistan’s most distortion‑ridden sectors: power and sugar.

The IMF’s directive requires:

- Full liberalization of the sugar sector

- Enhanced private participation in the power sector by next June

These reforms strike at the core of Pakistan’s political economy.

The sugar sector is dominated by politically connected conglomerates whose influence extends from parliament to provincial assemblies. Liberalization—removing price controls, export restrictions, and preferential subsidies—will face fierce resistance. Yet the IMF views this as essential to dismantling market distortions and improving competitiveness.

The power sector, meanwhile, remains a fiscal black hole. Circular debt continues to balloon, and losses persist despite repeated tariff hikes. The IMF’s push for private participation is aligned with global best practices; ADB’s energy-sector diagnostics have long argued that Pakistan’s state‑dominated model is unsustainable.

But the political cost is immediate. Private participation implies tariff rationalization, subsidy reduction, and stricter enforcement—all deeply unpopular measures in a country where electricity prices are already a flashpoint for public anger.

Economic Outcome: Reduced circular debt, improved sector efficiency, enhanced investor participation.

Political Cost: Resistance from entrenched lobbies, public backlash over tariffs, and potential provincial‑federal tensions.

Sovereignty vs. Sustainability: The Central Dilemma

The IMF’s 11 conditions collectively underscore a deeper philosophical tension: Can Pakistan achieve long‑term sustainability without ceding short‑term sovereignty?

The asset declaration requirement is emblematic of this dilemma. For many policymakers, it symbolizes external intrusion into domestic governance. Yet for investors, it signals a long‑overdue shift toward transparency.

Similarly, the mini‑budget trigger—if revenues fall short by December 2025—places Pakistan’s fiscal policy under external surveillance. Critics argue this undermines sovereignty; proponents counter that Pakistan’s fiscal sovereignty has long been compromised by structural weaknesses, not IMF oversight.

Forward-Looking Assessment: Can Pakistan Meet the Deadlines?

Given Pakistan’s political fragmentation, bureaucratic resistance, and entrenched economic interests, meeting all IMF deadlines will be challenging. The governance milestones—particularly asset declarations—are achievable but politically costly. Fiscal consolidation will depend heavily on inflation dynamics and the government’s ability to withstand lobbying pressure. Sectoral liberalization, especially in sugar and power, remains the most uncertain.

Yet if Pakistan does manage to comply, the payoff could be significant. Successful implementation would strengthen macroeconomic stability, improve sovereign creditworthiness, and unlock new avenues for foreign direct investment, particularly in energy, agritech, and manufacturing. Investors value predictability—and nothing signals predictability more than a government capable of meeting difficult structural benchmarks.

The cost of compliance is high. But the cost of non‑compliance may be higher still.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Opinion

The New Geometry of Global Finance: How Developing Nations Navigate the IMF, World Bank, ADB, AIIB, and IsDB

In the long arc of global development, few decisions shape a nation’s trajectory as profoundly as the choice of where to borrow. For developing countries—many juggling fragile currencies, widening infrastructure gaps, and volatile political cycles—the question is not merely how much financing they can secure, but from whom, on what terms, and at what cost to sovereignty and long‑term stability.

The global financial architecture has never been more crowded. The post‑war titans—the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank—still dominate the landscape, but they no longer stand alone. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) continues to anchor Asia’s development agenda, while two newer entrants—the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and the Islamic Development Bank (IsDB)—have carved out distinct roles by offering faster, more flexible, and often less politically intrusive financing.

For developing nations, this expanding menu of lenders is both an opportunity and a strategic puzzle. Each institution brings its own ideology, regulatory philosophy, and geopolitical baggage. Understanding these differences is no longer optional; it is a prerequisite for any government seeking to build roads, stabilize currencies, or simply keep the lights on.

This article unpacks the comparative strengths, weaknesses, and regulatory burdens of the world’s most influential development lenders—and offers a clear-eyed assessment of which institutions are best positioned to support developing nations in the decade ahead.

The IMF: The Doctor You Call When the House Is Already on Fire

The International Monetary Fund was never designed to be loved. It was designed to be necessary. Its mandate is not development but stabilization—an emergency physician for economies in cardiac arrest.

When a country’s foreign reserves evaporate, when its currency spirals, when investors flee and imports stall, the IMF steps in with a lifeline. But the rescue comes with strings—thick, tightly knotted strings.

IMF programs typically require governments to implement structural reforms:

- Fiscal tightening

- Currency adjustments

- Subsidy rationalization

- Governance reforms

- Monetary discipline

These conditions are often politically explosive. They can topple governments, ignite protests, and reshape entire economic systems. Critics argue that IMF prescriptions can be too harsh, too uniform, and too indifferent to local realities. Supporters counter that stabilization is impossible without discipline.

What is undeniable is this: IMF financing is the most conditional, most regulated, and most intrusive of all global lenders. It is also the fastest in crises and the most influential in shaping macroeconomic policy.

For developing nations seeking long-term development financing, the IMF is rarely the first choice. It is the lender of last resort—the institution you turn to when every other door has closed.

The World Bank: The Architect of Long-Term Development—With Bureaucracy to Match

If the IMF is the emergency doctor, the World Bank is the urban planner. Its mission is long-term development: reducing poverty, building institutions, and financing infrastructure, education, health, and climate resilience.

The World Bank’s two arms—IBRD for middle-income countries and IDA for low-income nations—offer some of the world’s most concessional financing. IDA loans, in particular, come with extremely low interest rates and long maturities.

But the World Bank’s generosity comes wrapped in layers of governance requirements. Borrowers must adhere to strict procurement rules, environmental safeguards, anti-corruption frameworks, and transparency standards. These are designed to ensure accountability, but they also slow down disbursement and complicate project execution.

For governments with limited administrative capacity, World Bank financing can feel like navigating a labyrinth of paperwork. Yet for those willing to endure the bureaucracy, the rewards are substantial: large-scale funding, global expertise, and long-term stability.

The World Bank remains a cornerstone of development finance—but it is not the fastest, nor the most flexible, nor the least regulated.

The Asian Development Bank: Asia’s Policy Partner With Moderate Conditionality

The Asian Development Bank occupies a middle ground between the World Bank’s governance-heavy approach and the IMF’s macroeconomic conditionality. ADB’s mandate is development, but its lending philosophy is more pragmatic and regionally attuned.

ADB loans typically require:

- Sector-specific reforms

- Governance improvements

- Project-level safeguards

But unlike the IMF, ADB does not demand sweeping national restructuring. And unlike the World Bank, its processes are often more streamlined and regionally contextualized.

For Asian developing nations, ADB is a familiar partner—predictable, moderately regulated, and aligned with regional priorities such as energy transition, digital connectivity, and climate resilience.

Its concessional financing is competitive, though not as generous as IDA. Its bureaucracy is real, but not suffocating. Its influence is significant, but not overbearing.

In the hierarchy of regulatory burden, ADB sits comfortably in the middle.

The AIIB: The New Power Broker With Leaner Rules and Faster Money

The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank is the newest major player—and arguably the most disruptive. Created in 2016, AIIB has positioned itself as a modern, efficient, and less politically intrusive alternative to Western-led institutions.

Its value proposition is simple:

- Faster approvals

- Leaner bureaucracy

- Fewer political conditions

- Strong focus on infrastructure

- Co-financing partnerships with World Bank, ADB, and others

AIIB’s governance standards are robust, but its conditionality is lighter. It does not impose macroeconomic reforms. It does not dictate national policy. It focuses on project quality, not political ideology.

For developing nations seeking infrastructure financing—roads, ports, energy grids, digital networks—AIIB is increasingly the lender of choice. Its rise reflects a broader shift in global power dynamics, as emerging economies seek alternatives to Western-dominated institutions.

AIIB is not without critics. Some argue it advances geopolitical interests. Others worry about debt sustainability. But its efficiency and flexibility are undeniable.

In the ranking of regulatory burden, AIIB is among the least restrictive.

The Islamic Development Bank: Development Without Political Strings

The Islamic Development Bank is unique—not only because it offers Shariah-compliant financing, but because its lending philosophy is fundamentally partnership-driven. IsDB emphasizes social development, equity, and shared prosperity.

Its financing structures—profit-sharing, leasing, equity participation—are often more flexible than traditional interest-based loans. Its conditionality is minimal. Its political footprint is light.

For Muslim-majority developing nations, IsDB is often the most culturally aligned and least intrusive lender. It supports:

- Agriculture

- Social infrastructure

- SMEs

- Human development

- Climate adaptation

IsDB’s funding volumes are smaller than the World Bank or ADB, but its impact is significant—particularly in Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia.

In terms of regulatory burden, IsDB ranks as the most flexible and least politically conditioned institution.

Comparative Analysis: Regulation, Speed, Flexibility, and Strategic Fit

To understand how these institutions stack up, it helps to evaluate them across four dimensions that matter most to developing nations:

1. Regulatory and Conditionality Burden

- Highest: IMF

- High: World Bank

- Moderate: ADB

- Low: AIIB

- Lowest: IsDB

2. Speed of Financing

- Fastest: IMF (crisis), AIIB (projects)

- Moderate: ADB

- Slower: World Bank

- Variable: IsDB

3. Flexibility of Terms

- Most Flexible: IsDB, AIIB

- Moderate: ADB

- Least Flexible: IMF, World Bank

4. Best Use Cases

- IMF: Crisis stabilization

- World Bank: Social development, climate, governance

- ADB: Regional development, infrastructure, reforms

- AIIB: Infrastructure, energy, digital connectivity

- IsDB: Social development, agriculture, SME support

The Strategic Puzzle for Developing Nations

Choosing a lender is no longer a binary decision. It is a strategic exercise in balancing:

- Sovereignty

- Speed

- Cost

- Political risk

- Long-term development goals

A country seeking to stabilize its currency may have no choice but to approach the IMF. A nation building a new port may find AIIB’s efficiency irresistible. A government investing in education or climate resilience may prefer the World Bank’s expertise. A Muslim-majority country seeking culturally aligned financing may turn to IsDB.

The smartest governments diversify their financing sources—leveraging each institution’s strengths while minimizing exposure to any single lender’s constraints.

The Next Decade: Who Will Shape Global Development?

The global financial order is shifting. The IMF and World Bank remain powerful, but their dominance is no longer unquestioned. AIIB’s rise signals a new era of multipolar development finance. ADB continues to anchor Asia’s growth story. IsDB provides a culturally aligned alternative for a vast swath of the developing world.

In the decade ahead, the institutions that will matter most are those that can combine:

- Speed

- Flexibility

- Sustainability

- Political neutrality

- Long-term developmental impact

By this measure, AIIB and IsDB are poised to expand their influence. ADB will remain a regional heavyweight. The World Bank will continue to lead on climate and social development. The IMF will remain indispensable in crises—but rarely welcomed.

Conclusion: The New Hierarchy of Development Finance

If we rank these institutions by their suitability for developing nations seeking accessible, low-regulation financing, the hierarchy is clear:

1. Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) — Most flexible, least political

2. Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) — Fast, modern, infrastructure-focused

3. Asian Development Bank (ADB) — Balanced, moderate conditionality

4. World Bank — Strong but bureaucratic

5. IMF — Essential but heavily conditioned

The world of development finance is no longer defined by a single pole of power. It is a competitive marketplace—one where developing nations, for the first time in decades, have real choices.

And in that choice lies the possibility of a more equitable, more responsive, and more multipolar global financial system.

Discover more from The Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

-

Governance1 week ago

Governance1 week agoPakistan’s Corruption Perception 2025: A Wake-Up Call for Reform and Accountability

-

Global Economy6 days ago

Global Economy6 days agoPSX Bull Run 2025: Why Pakistan’s Market Is Suddenly on Every Global Radar

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoPakistan’s Economic Pivot: Finding Resilience in a Turbulent South Asia

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoThe New Geometry of Global Finance: How Developing Nations Navigate the IMF, World Bank, ADB, AIIB, and IsDB

-

Global Economy5 days ago

Global Economy5 days agoThe Great Factory Shuffle: Can Pakistan Catch China’s Manufacturing Spillover?

-

Global Finance3 days ago

Global Finance3 days agoPakistan’s IMF Deal: Reform or Recoil?

-

Global Economy22 hours ago

Global Economy22 hours agoTrump’s December Address: The Reality Behind the Rhetoric

-

Events1 week ago

Events1 week ago🌍 Davos 2026: The World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Sets the Stage for Global Transformation